AMERICAN POPULAR MUSIC

ELEMENTS

The academic study of music and its cultural implication is known as MUSICOLOGY. Musicologists draw connections between music and the people and cultures who create and consume it. For many years, musicology mostly focused on the Classical Art Music of Western Europe with traditional music of other cultures studied by ethnomusicologists - and popular music was often overlooked as not worthy of academic study. Today, musicology has evolved to include the study of popular music trends with the understanding that mainstream music speaks toward a broader understanding of society.

When studying and discussing music, it is important to consider its cultural significance and also have a baseline understanding of music terminology and the theoretical elements that go into music composition, performance, and production. Musicians and researchers of music rely on a communal understanding of these elements when communicating about the art and science of music. These elements can be broken down into categories of properties to help distinguish different styles, eras, composers, regions, and pieces from one another. If you have music experience prior to this course (especially as a performer or a student of music), you might expect to discuss typical MUSIC THEORY terminology such as Rhythm, Melody, Harmony, Timbre, Dynamics, Texture, and Form (topics covered in Dr. Bove’s World Music and Music Appreciation courses). Most people, even non-musicians, already understand many of these concepts about the music they consume and, in fact, tend to seek out music based on personal preferences in these categories.

For the sake of studying popular music, we will be looking at some different properties that not only describe the specific elements of a piece of music, but help us to understand why the music is popular. Before we get any further into the scholarly study of popular music, however, we must have a brief discussion about the word “song”.

WHAT IS A SONG?

Most music consumers who are not trained musicians often refer to every piece of music as a “song”.

Anything played on the radio? Song.

8 minute instrumental track deep in an album? Song.

35-minute Mozart Symphony? Song.

Experimental acoustic “event” involving wind chimes, a bowling ball, and a hammer? Song.

This drives many musicians crazy. You see, there are dozens and dozens of labels to give a specific piece of music based on its structure, form, and length - and the term “song” is only one of them. In trained musician-land, when you’re not sure how to label the format of a piece of music, you just call it a “piece” or “work”. When you do know the form, you refer to it by its label like “symphony” or “tone poem” or “rondo” or “mazurka” or in some cases, “song”.

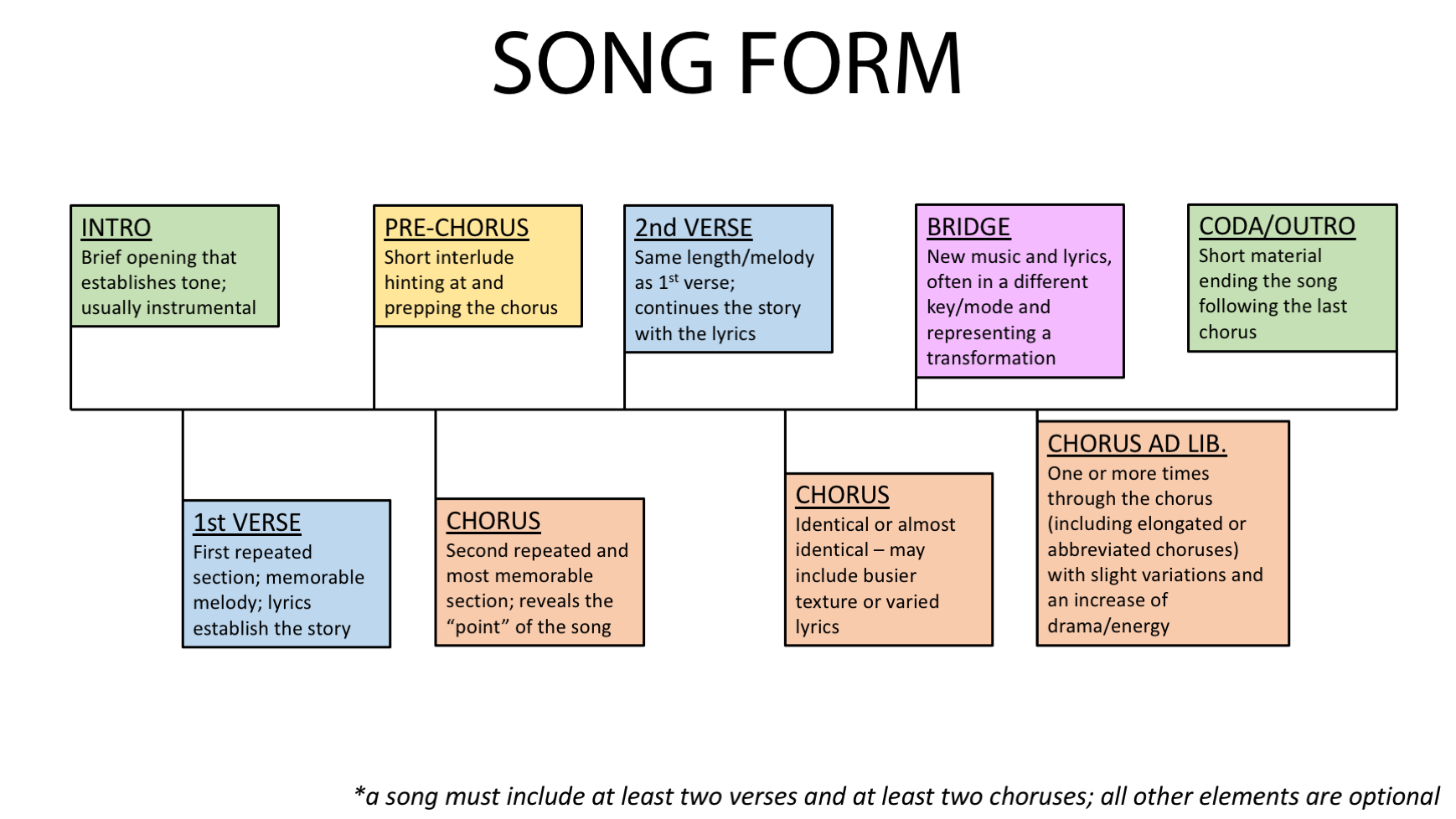

The definition of SONG in music is a piece - that almost always includes LYRICS (words verbalized in a musical way) sung by a singer - with a repetitive pattern of:

VERSE (same music, different lyrics each time)

CHORUS (same music, same lyrics each time)

And optional other elements like intro, outro/coda, build-ups, hooks, pre-choruses, instrumental interludes, a breakdown, or BRIDGE (a third section of new music and new lyrics that only happens once, usually about two-thirds of the way through the song and often in a different key or mode before transitioning back into another chorus).

Below, we can study the layout of a typical song with many possible inclusions from the list above:

Americans are obsessed with “song” and have been for a long time as we’ll find out in a few weeks. The most popular genres and popular pieces in these genres tend to be songs - because we love brevity and we (Americans in general) love the storytelling nature of lyrics. So, if the piece of music is considered American Popular Music - if it’s showing up on the Billboard Charts in some category or another - it’s probably a song. Since we know this, we can use the term “song” pretty confidently when discussing most of the music in this course - and instead of focusing on its form (although occasionally, a piece’s break from the traditional song form might generate a novel element worthy of note), we will focus on other elements of the music that have more variety in the music we’ll be studying.

Sometimes, we might refer to a song as a SINGLE. This doesn’t have to do with the format of the song but in the way it was released. Singles are noteworthy because they are usually released outside of a musical album or as a preview to an upcoming album. Prior to digital song distribution, singles would be released on a small record as a single song or 3-4 songs that were a way to keep an artist in the public eye, promote an upcoming album with the single on it, and provide a more affordable way for young music consumers to obtain songs for at-home listening. With today’s modality of music streaming and digital downloads, singles still serve as a way for artists to reach their fans faster and more often while this new way of obtaining music a la carte has made selling albums harder for artists.

Throughout modern popular music history, most songs have been released on a larger ALBUM (whether that be a physical album of vinyl records or a digital album available for download or streaming). An album is a collection of songs meant to be listened to in order from the first song to the last song, usually performed by the same artist (but not always). Album titles often reflect the larger idea of the whole album or sometimes are named for a specific (potentially popular) song on the album. Albums of songs tend to have been written and/or recorded by a single artist or music group in a specific time frame (like over the course of a year) and, oftentimes, have a thematic element that runs through the songs while still providing some contrast and variety on the album from song to song. Albums that are highly conceptual and thematic are referred to as CONCEPT ALBUMS (meaning that the artist has a very specific topic, subject, mood, or story they’re trying to express within the structure of the album).

If all of this is really fascinating to you, here’s more information at Analyzing Common Song Structures by Producer Hive and Intro to Song Structure from Renegade Producer.

writing about songs IN AN ACADEMIC WAY …

When you are writing about a song, put the title in “quotation marks” and be conscious of spelling and capitalizations.

Song titles do not need to be italicized (although you will often see larger works of classical music italicized with no quotation marks). In popular music, albums are usually written in italics (see examples below) … although not every song is from an album. Some artists intentionally spell words wrong, use slang, numbers, or lowercase letters instead of uppercase. Using the correct spellings of the titles as published by the artist in your writing shows respect for the artist and their work. Some songs may have a title and “subtitle” which usually shows up in the form of (parentheses) around the subtitle. This helps to distinguish the song from others with the same title - or provides more context for the theme or story behind the lyrics.

When identifying artists, most songs are by a specific artist or band but sometimes there are collaborations between two artists. When this happens, you might credit both artists equally or credit one artist as the main contributor with the other as a “featured artist” of the song. When this happens, the featured artist on the track, will be denoted by the abbreviation: “feat.” or “ft.” Here are some examples:

“Girls Like You” - Maroon 5 feat. Cardi B

from the album Red Pill Blues (2017)“Stuck With U” - Ariana Grande and Justin Bieber

from the album Purpose (2015)“Montero (Call Me By Your Name)” - Lil Nas X

from the album Montero (2021)“good 4 u” - Olivia Rodrigo

from the album Sour (2021)

For the sake of this class - since we will be focusing on what makes music popular - a traditional musicology/music theory collection of music elements fails to capture the “it factors” of what makes our culture’s most beloved songs popular. Therefore, we will be using a different collection of elements to analyze the music we study in this course as developed by the creators of ECHO NEST.

ECHO NEST

In 2005, graduate students at MIT Media Lab (Tristan Jehan and Brian Whitman) developed an online music intelligence known as Echo Nest as part of their dissertation project. Echo Nest is designed to collect data from popular songs and generate an “audio fingerprint” that can be used in music marketing, consumer relations, song identification and recommendations, playlist generation, and more. The computer algorithm looks at eleven musical properties in popular music to produce each song’s unique profile. In 2014, Echo Nest was purchased by Spotify and now falls under the Spotify API (Application Programming Interfaces). You’ve likely encountered this program if you’ve ever received a music app’s recommendation for artists you might like or streamed an online radio station.

What Makes Popular Culture Popular?

Product Features and Optimal Differentiation in Music

In a 2017 study by Columbia professors, Noah Askin and Michael Mauskapf, the Echo Nest was used to analyze the elemental properties of just under 27,000 songs off Billboard’s Hot 100 Chart to investigate the predictability of popularity. The results of the study, published in the peer-reviewed academic journal, American Sociological Review, indicate that the most popular songs in America achieve a balance of novelty/innovation and familiarity/conformity to genre:

We find that, in addition to artist familiarity, genre affiliation, and institutional support, a song's perceived proximity to its peers influences its position on the charts. Contrary to the claim that all popular music sounds the same, we find that songs sounding too much like previous and contemporaneous productions—those that are highly typical—are less likely to succeed. Songs exhibiting some degree of optimal differentiation are more likely to rise to the top of the charts.¹

The study above focused on eight of the eleven Echo Nest music properties as outlined below and we will continue to reference this study later in the course …

THE POPULAR MUSIC ELEMENTS

as developed by the creators of Echo Nest

ACOUSTICNESS

Definition: Acousticness refers to the balance of purely acoustic to purely electronic elements in a musical track.

The most acoustic tracks are recordings that feature all naturally-produced sound such as raw human voice, acoustic (non-electronic) instruments like acoustic guitar, upright bass, drum kit, strings, horns, or other instruments that can be played without plugging them into electricity.

More electronic tracks will include elements like filters and auto-tuning on the voice (an element once used to hide imperfections but now embraced as an obvious feature); electronic instruments like synthesizer, electric guitar, electric bass, or electronic drum set; and computer generated beats, sounds and effects (such as the “beat drop” elements in Electronic Dance Music).

To learn more about auto-tuning, check out Pitchfork’s article: How Auto-Tune Revolutionized the Sound of Popular Music.

Over the past 100 years, “acousticness” has become less popular and “electronicness” has become more popular in mainstream music consumption. This is due, in large part, of the increased development of music technology - both in electrifying acoustic instruments and developing digital spaces for the creation of music. Considering the electric guitar was not even invented until 1936, “electronicness” has gained a strong footing in the popular music scene that shows no sign of letting up.²

The desirability of acoustincness depends on the genre - with many danceable genres tending to favor electronicness and many genres that value a more sensitive touch (like singer/songwriter, Gospel, folk, or bluegrass) preferring natural, acoustic elements. In modern popular music, “acousticness” is often seen as an intimate or vulnerable novelty - finding its way into re-releases or “unplugged” versions of songs and albums many years after the original electronic release of a track.

Examples:

Fully Acoustic

”Blackbird” - The Beatles (1968)

Fully Electronic

”Ghosts ‘n’ Stuff” - deadmau5 (2009)

DANCEABILITY

Definition: Danceability is the ease of which a song can be danced to.

Factors that play into danceability are purely rhythmic (other musical elements like melody, harmony, or instrumentation and non-musical elements like lyrics do not affect danceability). Danceable songs are often said to have a “good beat” but this really speaks to TEMPO (speed of the music), consistency and regularity of the beat, and strength of beat (how loud the underlying beat is in comparison to other elements of the song).

For a song to be danceable, it must fall into specific ranges of tempo (there are tempi that are too slow, too fast, or too “medium” to comfortably dance to for most human bodies). Gravity and range of motion, as well as the type of dance performed, also play into this element. There are slow songs that are easier and more challenging to dance to just like there are fast songs that are easier and more challenging to dance to - depending on what type of dance you’re doing.

The song must also have a steady beat. If the beat is constantly slowing, speeding, changing times, or tempo, the dancer will not feel comfortable and confident about dancing. Most pop songs are in symmetrical time signatures like 4/4 (meaning four beats per measure) and this makes it much easier to dance because humans tend to dance symmetrically using two legs and two arms. The beat must also be strong - meaning that the instrument generating the beat (usually the drum kit but also possibly guitars, bass, keyboards, or electronic instruments) are landing each beat consistently, tightly on the beat, and at a significant volume compared to the rest of the elements of the track.

Finally, “danceability” also carries generational considerations. The context for what types of dances were performed and valued at the time of its release may play into a decision as to whether or not a song should be considered danceable. While many songs from 100 years ago are still considered to have a “good beat” and could be danced to by modern listeners with modern moves, some won’t feel danceable unless the popular dance trends of the time the song was released are applied. Almost every popular song is danceable - it’s just a question of how easily.

If you have any interest in curating great, danceable playlists or DJ-ing dance events, check out these Helpful Tips from Stanford Social Dance.

Examples:

Highly Danceable

”Happy” - Pharrell Williams (2014)

Highly Undanceable

”The Way I Feel Inside” - The Zombies (1964)

ENERGY

Definition: A slightly subjective element, this gages the intensity and power of a given track by taking into account factors such as how fast, loud, or noisy a track is. In addition, the intensity and emotional rawness of the performance should also be considered (as some slower, less noisy tracks could still be considered high energy).

One question to ask when gaging the energy of a track is: does it get your heart pounding or “amp you up”?

Higher energy is not always the goal of a song (and the lack of energy is not a failure of the artist). Low energy music does a great job at conveying feelings like calm, contentedness, peace, apathy, despair, fear, or depression. When a song achieves this high-quality low energy level, it can still result in a popular hit (check out the Roberta Flack low energy song below that was #1 on the charts in 1972!).

The recent popularity of ambient, shoe-gaze, and lo-fi music as a sort of “life soundtrack” to be played while moving through the day’s more menial tasks demonstrates the market for low-energy music. However, most breakout and hit songs (as well as most people’s favorite song) tend to have a considerable amount of energy as energy tends to play a huge factor in the audience’s connection to a song.

Examples:

Very High Energy

”Walking on Sunshine” - Katrina & The Waves (1985)

Very Low Energy

”The First Time I Ever Saw Your Face” - Roberta Flack (1972)

INSTRUMENTALNESS

Definition: Instrumentalness captures the balance between a purely instrumental track versus a purely vocal track.

“Instrumental” implies any musical sound created by an object other than the human voice. In this context, electronic and computer-generated digital sounds and music fall into the instrumental category.

While most pop songs contain a vocal element (because lyrical content is often just as, if not more, important to many consumers than the musical elements), the balance between vocal and instrumental elements vary from song to song.

A purely vocal track is called A CAPPELLA and may consist of a single vocalist singing with no accompaniment or multiple vocalists singing in harmony or counterpoint (as is typical in most a cappella music groups such as Pentatonix or the soundtrack to the film Pitch Perfect). Purely instrumental tracks are simply referred to as INSTRUMENTALS and include many popular songs you’ll probably recognize but not remember the name of since there are no lyrics to draw a title from. The Champs’ 1958 classic “Tequila” is considered one of these instrumentals - as long as you ignore Danny Flores shouting the title several times throughout the song …

An analysis of instrumentalness should also consider what kinds of instruments and voices are coming together to create the track. Before deciding how instrumental or vocal a song is, make a note of what you’re hearing:

Are there vocals? If so, how many singers/rappers/speakers?

Are there instruments? What kinds? How many?

What is the balance (amount of time and volume) struck between vocal and instrumental elements?

People without much experience identifying INSTRUMENTATION (the collection of instruments and voices in a given piece) tend to overlook instruments like: electric bass, backup singers, percussion in addition to drum kit, keyboards/synthesizers, and strings. When identifying what you hear in a track, run a mental list of the various voice types and instruments you’re trying to listen for and rule out rather than skip over.

Examples:

Fully A Cappella

“Don’t Worry, Be Happy” - Bobby McFerrin (1988)

Fully Instrumental

“Green Onions” - Booker T. & The MGs (1962)

LIVENESS

Definition: Liveness refers to the balance of live-captured musical elements versus produced, edited, or post-produced elements in a given track.

The most live musical track would include all human musicians with every performer present in the recording space all singing and/or playing their instruments together at the same time, with no editing to the track in post-production.

The most produced musical track involves a heavy amount of computer manipulation with all or most of the music generated digitally (through the use of beatmakers or other computer softwares that perform pre-programmed music in place of a human performer) or live elements (such as singers or human instrumentalists) receiving post-recording treatments such as filters, auto-tuning, looping, layering effects, and more.

Most songs released today are a balance of live and produced sound. Even in bands where everyone sings and plays instruments by hand, each performer is often recorded separately and then the individual tracks are edited and balanced to one another in a post-production MIX. In addition, the inclusion of non-live elements such as digital beats, samples, or filters skew songs further into produced and away from liveness.

Modern music consumers very rarely hear truly live music in the popular music genres except when attending live concerts or listening to “live albums” that are usually recorded at concerts. The music industry has come under scrutiny for many decades when artists are caught “lip-syncing” to pre-recorded, produced recordings of themselves at so-called “live concerts”. The ethics of this practice are a heated topic as the expected amount of concert production (including spectacle like choreography, movement, elaborate costumes, and staging) can make it difficult for even the most talented artists to perform their own music live at their normal level of success without suffering extreme fatigue.

Note that “liveness” is not the same as “acousticness”. A human musician performing on an electric guitar would be considered both live and electronic/not-acoustic.

Examples:

Fully Live

“Unbreakable (Unplugged)” - Alicia Keys (2005)

Fully Produced

”Levels” - Avicii (2011)

SPEECHINESS

Definition: Speechiness is defined by the amount of “spoken word” as opposed to vocal lyrics that are sung.

To register anywhere on the speechiness scale, there has to be human voice at least somewhere on the track. Most rap and hip-hop tracks have a high level of speechiness as rap is a type of highly-rhythmic spoken word. Many songs in these categories still might include a sung chorus or hook (especially if the rapper is featuring a singing vocalist) so it is not safe to assume every rap and hip-hop track is 100% speechy.

Likewise, many songs that are mostly sung may have a “talk breakdown” where the singer stops singing to talk to the audience (or themselves) - or the song might feature an artist who raps during a verse or bridge. In addition, some singers include a spoken element to their style of singing so spoken word may be imbedded in mostly sung lines of lyrics.

Instrumental songs are almost always 0% speechy but may show up on the speechiness chart if a word or words are spoken or shouted at some point during the song (again, The Champs’ “Tequila”).

Examples:

High Speechiness

”Be (Intro)” - Common (2005)

Balance of Speech/Singing

”Leave the Door Open” - Silk Sonic (2021)

No Speechiness

”Como La Flor” - Selena (1995)

TEMPO

Definition: Tempo is the average speed of a song, and the word Tempo is the Italian word for “time” (most academic music terminology comes from the Italian language).

Speed in music is measured by BEATS PER MINUTE (BPM). The “beat” is the pulse of the music in terms of how fast or slow it flows by (consider the pulse you tap your foot to while listening to a song or that a conductor would “wave their arms to” if conducting the music).

Tempo for a song might look like: 160 bpm (fairly fast), 120 bpm (medium-fast), 92 bpm (medium), 60 bpm (slow), 48 bpm (very slow), etc. Most musical TEMPI (the Italian plural of tempo) are even numbers (rather than odd) and many are mathematically related to 60 bpm (the length of a second or a standard, healthy resting adult heartbeat). Tempi ranges have Italian words associated with them, as well, like Allegro, Presto, Lento, Andante, etc. For the purposes of this course, you will not be expected to use these terms though you might recognize them if you have some musical training.

Most popular music is meant to be easily consumable and/or danced to which results in most songs having one set, precise tempo for its duration. But tempo is not always stable for a song. Tempo can change in many ways including:

Speeding up (providing a feeling of energizing) - the Italian word for this is accelerando

Slowing down (providing a feeling of relaxing) - the Italian word for this is ritardando

DOUBLE TIME or HALF TIME - this occurs when the music immediately doubles in speed or halves in speed, resulting in the same effect as slowing or speeding, but in a more sudden, dramatic way

Immediately jumping to a new, unrelated speed (faster or softer) that signals a different section of the music

Finally, unskilled musicians may speed up or slow down due to a lack of control or awareness - and this tends to make an audience generally uncomfortable

https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-53167325

Beats per minute can be calculated by counting how many beats in a song occur during a clocked minute. However, there are also musical tools like METRONOMES which can automatically generate a BPM or determine a BPM from a generated beat. During this course, you will be expected to accurately identify tempo in musical examples. To do so, please download any Free Metronome App on your device or head to Google’s Free Online Metronome. Dr. Bove uses the Pulse app for iPhone.

A recent article published by the BBC tracks tempo of pop music over the last decade and makes the claim that Pop music is getting faster (and happier) in the UK. It will be interesting to see how the global pandemic of 2020 affects this trend in the years to come.

When analyzing a song for its tempo, it should be first decided if the song has one set tempo or if it changes tempi (as well as in what direction and how often). Then, determine what the tempi are (by using a metronome) and decide if they’re related (like half time and double time) or if the multiple tempi are unrelated.

Examples:

Fast/Consistent Tempo - 200 BPM

(with half-time choruses)

”The Ghosts of Me and You” - Less Than Jake (2003)

Slow/Consistent Tempo - 52 BPM

”Always and Forever” - Heatwave (1976)

Medium to Fast/Changing Tempo -

120 - 254 BPM

”Rock Island Line” - Johnny Cash (1970)

This song uses accelerando to change tempi

VALENCE

Definition: The emotional/mood positivity of the musical track.

Potentially the most difficult quality to objectively quantify, Valence is designed to highlight the emotional mood of a track on a positive to negative scale.

Positive mood attributes could include words like: happy, hopeful, energized, peaceful, loving.

Negative mood attributes could include words like: sad, angry, scared, threatening, hopeless, pained.

Most songs in MAJOR KEYS (drawing their melodies and chord patterns from a major scale) sound happy. Most songs in MINOR KEYS (drawing their melodies and chord patterns from a minor scale) sound unhappy. However, some major songs still sound sad and minor songs can still sound happy. Songs in major with a high level of electronicness may sound distant and unemotional and could score lower on the valence scale when compared to a song in major with more live and acoustic elements.

Music scholars must be aware that the intended mood of a musical work does not necessarily correlate with the mood it elicits from its audience. For instance, a sad, nostalgic song may trigger positive emotions in a listener who needs the space the song provides to process cathartic emotions. A Death Metal aficionado will likely derive great pleasure from listening to a song with a dark, creepy mood. In contrast, a happy “Bubblegum Pop” song could elicit waves of righteous nausea from a Punk. As we examine the intended mood of a song, it’s important that we set our personal values and preferences aside. It is also never appropriate to criticize music based on our personal preference toward the genre or artist. Music scholars must maintain a level of detached professionalism when objectively assessing and analyzing the qualities and artistic intention of various musical works.

Consider The Killers’ “Mr. Brightside”- the song is actually quite sad but many people feel happy or energized listening to it. What is happening with the Valence in this tune?

Examples:

High Valence

”Wake Me Up Before You Go Go” - Wham! (1984)

Low Valence

”Dust in the Wind” - Kansas (1977)

*Note that in addition to the eight elements above the Echo Nest algorithm also includes the sonic features of Key (the key signature a song is in), Mode (whether the song is in major or minor), and Time Signature (beats per measure). While these three factors may influence a song’s popularity, they do not do so as much as the other eight described above and one needs a specific set of music skill/training to be able to identify these final three with accuracy. Discussion of these elements will not be required for this course.

ANALYZING MUSIC

USING THE ECHO NEST ELEMENTS

Now that we’ve had a chance to understand how each of these eight elements work, let’s put them to use by analyzing the 2021 Song of the Summer, BTS’s “Butter”. First, think of every element on a 0-10 scale where 0 is the absence of the element and 10 is maxing the element out. This analytical process get subjective and each music scholar may have slightly different answers than each other but should be in mostly close range (and if not, well that’s where the real fun of artistic interpretation might be coming into play!). The one element that will not be rated on a 0-10 scale is Tempo because there is a set tempo for each song with no room for interpretation - this element is essentially math.

THE POPULAR MUSIC ELEMENTS OF BTS’S “BUTTER” (2021)

Acousticness (0-10)

Dr. B’s Rating: 2

Reasoning: All of the instruments are electronic or digital. All the voices are treated with post-production auto-tuning and other filters to create a clean, polished track. The rating is not 0 because the voices are real human voices.

Danceability (0-10)

Dr. B’s Rating: 8

Reasoning: The beat is very consistent and strong. There are a handful of moments where the beat drops out for one or two moments, keeping the score lower than 10. The tempo is a little on the slow side for truly energized dancing - if it was a little faster, the score might be higher.

Energy (0-10)

Dr. B’s Rating: 7

The number of voices and layers of musical lines contribute to high energy. Toward the end, there are several moments where a group of men shout and call out which gives a feeling of a fun party. The tempo is a bit on the slow side which lowers the energy as does the minimal-ness of the melodic material. Most of the melodic material has a downward contour which builds a sense of release or relaxation rather than building energy.

Instrumentalness (0-10)

Dr. B’s Rating: 4

The vocals are the main feature of the track - with 7 vocalists (4 singers and 3 rappers) and much of the vocalization occurring in tight harmony. The instruments on the track are electronic drum set, electric bass, and synthesizer. At around :57, a tambourine is added, though this is through electronic layering and not live. 1:32-1:50 features a synthesizer solo.

liveness (0-10)

Dr. B’s Rating: 0

This song is extremely produced. Each voice has been manipulated to achieve perfect pitch accuracy, resonance, and balance. The moments of MELISMA (when a voice moves through different notes on the same syllable of a word) are achieved through auto-tuning. All of the instrumental tracks sound like they have been produced digitally rather than by musicians playing instruments.

speechiness (0-10)

“Acoustic Fingerprint” of BTS’s “Butter”.

Dr. B’s Rating: 4

Reasoning: The section from 1:50-2:06 is rapped as well as 2:24 to the end. The opening lines of the verses have a spoken quality to them even though they are sung. The pre-chorus and chorus are very obviously sung.

tempo (30-300 bpm)

Dr. B’s Rating: 112 BPM

Reasoning: The number was reached based on tapping the tempo on the Pulse app for iPhone.

valence (0-10)

Dr. B’s Rating: 9

Reasoning: This song is in major and features several voices taking turns and singing in harmony which increases a sense of happiness and cohesion. The energy increases throughout the song and much of the transitional material has a rising melodic contour to it, promoting optimism and a positive mood.

REFERENCES

1. Askin, Noah, and Michael Mauskapf. 2017. "What Makes Popular Culture Popular? Product Features and Optimal Differentiation in Music." American Sociological Review; 82, no. 5: 910-44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26426411.

2. “The Birth of the Electric Guitar.” Yamaha. https://www.yamaha.com/en/musical_instrument_guide/electric_guitar/structure/