THE PRE-RECORDING ERA

INDIGENOUS MUSIC

Frances Densmore recording Native American songs sung by Mountain Chief; Sioux (1915)

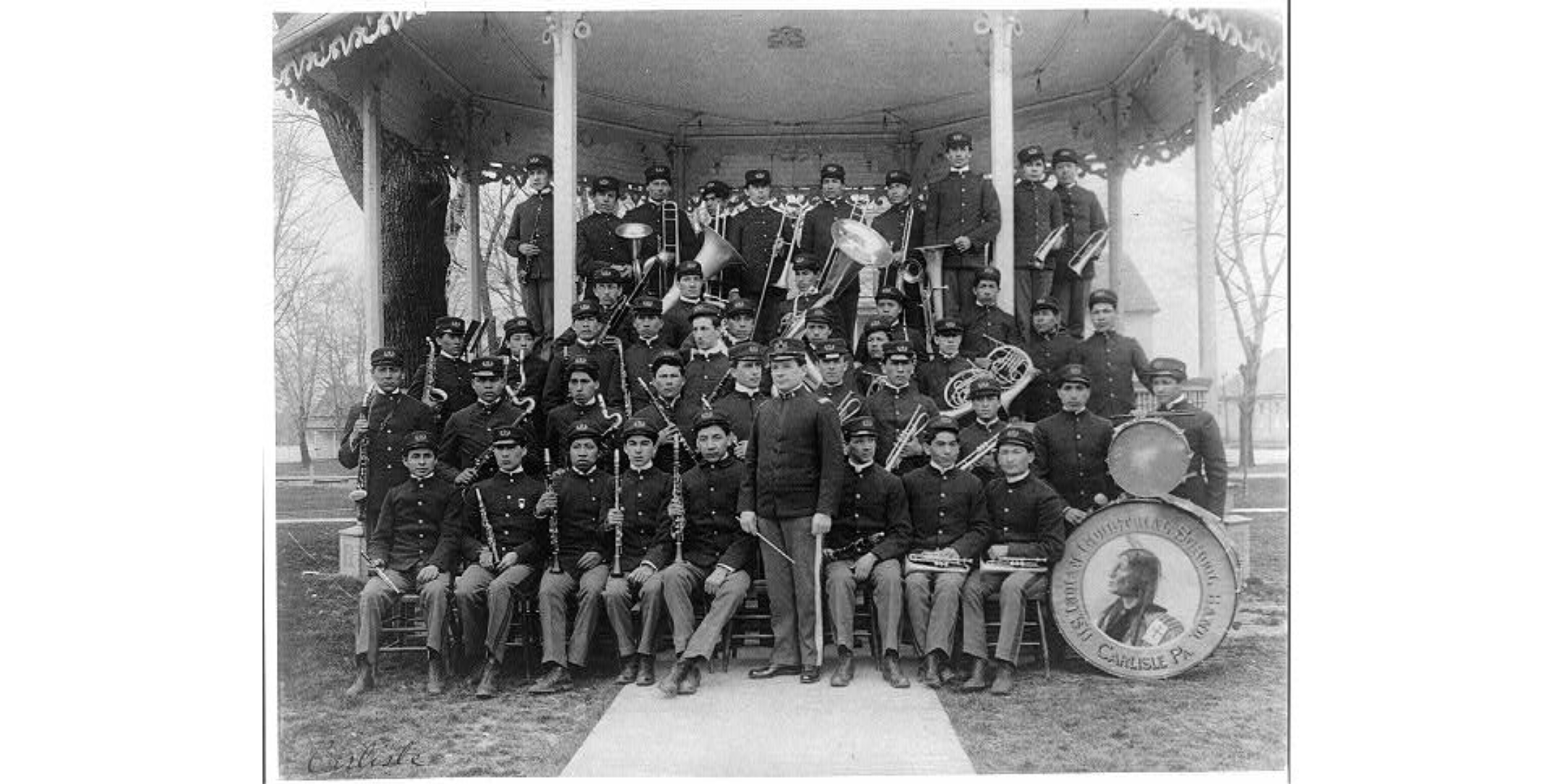

Carlisle Indian School, Carlisle, Pa. Band posed at the bandstand (1901)

Prior to the colonization of the North American continent by Europeans, the indigenous Americans developed a rich culture of musical traditions. This music was by no means a monolith - with some similarities and many difference between practices from the hundreds of tribal groups across the many regions of North America. With exceptions, music tended to be considered both a sacred and secular activity with singing and drumming as the main source of sound production and other instruments like flutes and rattles supplementing the sound. Music and dance often went together and was not something reserved for “professionals” as in many European society, but rather participated in by the entire tribe with different roles for men, women, and children. Music was used in religious practices, prayer, ceremonies, celebrations, and mourning.

When Europeans colonized the American continent, indigenous music practices were disrupted due to European extermination via genocide or assimilation via religious and cultural indoctrination. One method of Anglo-American assimilation included replacing indigenous music practices with the singing or playing of Christian hymns with voice and with European-style brass bands. This was often done in assimilation facilities for children known as RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS which separated children from their families and heritages and forced them to practice the ways of Anglo-Americans until their traditional practices were erased. Residential or Boarding Schools continued to operate in Canada and the United States through the 1980’s.

Young Spirit performing at a Pow Wow in 2012.

Today, indigenous Americans are working hard to reclaim or keep their music alive in traditional practices, performances at POW WOWS and other cultural events designed to support and strengthen tribal pride, and through education. A Pow Wow is a local or national festival where indigenous Americans from different tribes come together to build community and share, teach, and learn traditional practices to one another.¹

MUSIC OF THE COLONIES

NEW ENGLAND

The New England colonies of the upper East coast were established beginning in 1620. Settlers crossed the Atlantic from Europe to establish colonies in America where they could practice a strict and conservative form of Christianity called PURITANISM. The early Puritans of America limited their music performance and consumption to mostly SACRED MUSIC (religious music) rather than SECULAR MUSIC (non-religious music). This sacred music would have been Christian in nature consisted of four-part homophonic chorales with text directly from or inspired by the bible. HOMOPHONIC is a music term that describes a texture wherein one voice part (usually the soprano) is an obvious melody with the rest of the voice parts (usually alto, tenor, and bass) supporting with harmony notes as the piece progresses through chords. The early New Englanders mostly sang these religious songs (called HYMNS or specifically PSALMS if pulled directly from the Book of Psalms from the Bible) as composed in Europe.

A hymn or psalm book was needed to keep track of the words while a song book would be used to reference the melodies they would be sung to. Often, different hymn texts could be mixed and matched with different songs and it was up to a chorister or music leader of the church choir or congregation to plan the hymns and songs for each service. Most congregationalists had no music training or literacy so it was also up to the music leader or DEACON to teach songs by rote or lead the congregation through them via call and repeat. This slow, drawn out method of non-notationally based performance was referred to as THE OLD WAY and was considered the preferred style of congregational singing even as REGULAR SINGING (singing to song books with music notation) was reintroduced in the early 18th century.

SINGING SCHOOLS

Eventually, church leaders and music directors grew tired of dragging congregations through important music during services and felt THE OLD WAY had strayed too far from the preferred notation-based performance practice, so they devised a way to build musical literacy in their communities. SINGING SCHOOLS were opened with the goal of teaching churchgoers and children how to read music and how to sing well to improve the congregational singing at church. This is the first example of music education in Anglo-America. Singing Schools eventually became a center of socializing and leisurely pastime and some churches regretted their development as it turned some congregation members into vain divas.² The singing schools would eventually evolve into American public school music programs with the help of LOWELL MASON, a composer and choir director who established the first public school music program for children in Boston in 1838 as well as supporting the development of public school music teacher training programs.³

“Chester” - William Billings (1778)

Often considered Anglo-America’s first professional composer of original music, WILLIAM BILLINGS was a product of the American singing school tradition. He published the first collection of American music titled the New England Psalm-Singer or American Chorister in 1770 which included 120 tunes. His song “Chester” became the unofficial anthem of the American Revolution with its combination of religious and patriotic lyrics and its melody blending a balance of folk and militaristic elements.⁴ Below is the first verse of the song:

Let tyrants shake their iron rod,

And Slav’ry clank her galling chains,

We fear them not, we trust in God,

New England’s God forever reigns.

THE COLONIAL SOUTH

Many of the colonies on the southeastern coast of America were founded for economic reasons and its settlers tended to worship in less conservative Christian sects than their northern neighbors such as Anglicanism. The South enjoyed more leisure time and more secular music than the North. The South also relied less on singing schools and music literacy, opting for rote memorization, call and repeat, and, eventually, a unique “simplification” of notation called Shape Note Singing.

Holly Springs Sacred Harp singing: Hallelujah, #146 as recorded by Alan Lomax (1982)

SHAPE NOTE SINGING (FASOLA)

While shape note singing was invented in northern singing schools, it took hold to a much greater extent in the American South. SHAPE NOTE SINGING is a type of music notation in which pitch is not only represented by position on the staff, but also a geometric shape to the note head (such as a circle, square, triangle, etc.). Shape Note Singing was also called “Fasola” Singing because instead of singing a scale on the syllables: Do-Re-Mi-Fa-So-La-Ti-Do, the syllables would be replaced with the repetitive: Fa-So-La-Fa-So-La-Mi-Fa.

A Shape Note hymn out of The Sacred Harp

The main hymnal of shape note singing, The Sacred Harp, was first published in Georgia in 1844. The singers sit in a square shape with each voice part in one section (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) and the leader in the middle as well as many singers will “chop” their arm up and down rhythmically to keep the beat. Singers in the group are mostly amateur and perform with loud, belting or shrill tones that provide energy and fervor without necessarily sounding polished or “pretty”. The group will usually sing through a hymn once with just the Fa-So-La syllables for practice on the melody and then switch to the actual religious lyrics on a second time through.⁵

DANCING

While dancing was mostly discouraged in more conservative New England, social dancing was a part of secular life in the American colonial and post-colonial South. Dancing was usually a part of social gatherings such as festivals, feasts, holidays, and balls. Most dance music and dance steps originated in Europe and were based on the tradition that emerged from Renaissance era France. Music was mostly instrumental (played by a combination of strings, woodwinds, or keyboards) and most dances were performed by paired couples or larger groups in strict formation. Dances tended to be a formal affair with specific choreography delegated to specific music and it was a sign of wealth and high class to be able to know the steps and dance them well. Only those with enough money and time could learn and show off the newest, trendiest dances. Eventually, these types of COUNTRY DANCES evolved into a strictly American style called SQUARE DANCING as the secular dance music of the Southern United States evolved into the American genre of Country music that we’ll cover in a later week.

MUSIC OF ENSLAVED PEOPLES

The Work Song of the enslaved Africans saw little change as it developed into the Prison Work Song of the imprisoned African American.

At the same time that music of the Anglo-American colonists was developing, the enslaved peoples of the American South were also creating their own music forms. Enslaved Africans from all over the African continent were sent to work in houses and on plantations throughout the American South. Oftentimes, people working in the same house or on the same land came from different tribal groups and regions of Africa and did not share language, culture, or religious practices. As with the indigenous Americans, colonists developed assimilation tactics to erase the enslaved peoples’ histories and cultures, replacing them with English names and practices as well as Christianity. One of the first types of music to be documented from this community of enslaved, ethnically-mixed Africans was the WORK SONG. Work songs were developed as a way to pass the time and keep a productive rhythm when completing plantation tasks such as working fields or completing other repetitive tasks on the property. These songs were usually CALL & RESPONSE and would consist of a single individual calling the first half of a phrase with the rest of the participants responding to complete the idea with an answer or complimentary statement. Lyrical content could range from describing the work itself, to Christian themes, to subversive codes and secret messages about escape, uprising, and freedom. This type of song would eventually evolve into the BLUES (which we will cover in detail in our Jazz unit) but the prevalence of the work song continued after the Civil War in Black prison work camps and chain gangs.

In addition to the call and response texture Africans brought other musical elements that would prove incredibly important to the development of a uniquely American sound - most notably in the area of rhythm. Notably, the music of enslaved Africans relied more heavily on SYNCOPATION than the folk and Classical musics of the European colonists. Syncopation is a rhythmic effect that adds stress, weight, and often length to notes “off” the main beat one would typically tap the foot to when listening or performing music. The result is a feeling of intensity, excitement, or energy where there would otherwise be predictability - almost a sense of tripping forward in the music. Another rhythmic feature that made its way into American music via African culture is polyrhythm. POLYRHYTHM is a concept where two seemingly incompatible rhythms are performed at the same time and manage to line up with regularity at certain intervals.

Imagine if you and a friend each took a number to count to evenly (let’s say 5 and 7) and you both took exactly 10 seconds to count to your number. You would both start at “one” at the same time and over the course of the 10 seconds, the friend counting to 7 would count slightly faster than the friend counting to 5. After 10 seconds, if you were to start over, you would both meet at “one” again for the next 10 seconds - so on and so forth. This is an example of 5:7 polyrhythm.

When you tap your foot along to the drum beat examples in this video, you’ll feel stress and weight between your foot taps - that’s syncopation.

When two seemingly-incompatible beat numbers overlap and sync up at the repeat of their pattern, that’s called polyrhythm.

“Julie” - Rhiannon Giddens (2015)

Another enormous contribution to American music by the enslaved Africans is the first original American instrument. The BANJO is an instrument developed by combining the roots of a West African string instrument (likely the akonting or banjar) with elements of European string instruments such as the guitar. The resulting banjo had a body made from a dried gourd or drum frame with a neck, head, and four tunable strings. The banjo was used to accompany singing (as seen in the video of Rhiannon Giddens) or as a solo instrument or to make music for dancing. Eventually, the instrument gained popularity and recognition as it was integrated into Anglo-American entertainment forms by way of Minstrelsy music (see below). Eventually, a fifth drone string was added to some banjos leaving the four-string instrument that could be played more flexibly popular in Jazz and Parlor music and the five-string instrument pushing into the more harmonically simple but technically complex genre of Bluegrass.⁶

Today, Congo Square still serves as a meeting place for making African music.

While most forms of traditional African music-making were generally banned by Anglo-American captors, New Orleans was a unique community where enslaved Africans were granted certain privileges that afforded them the ability to preserve culture. Louisiana was a territory controlled by Spain and France before it became an American state and the Catholic French and Spanish were much looser with restrictions on enslaved Africans than their English counterparts. In New Orleans, enslaved people were granted Sundays as a day of rest and were allowed to intermingle and socialize in a plaza called CONGO SQUARE (originally Place des Negres). Here, they had the opportunity to practice authentic African music and dance tradition including singing in native languages and drumming which was banned in the English colonies. These looser restrictions and the intermingling of races and classes in New Orleans are a likely causation for the plethora of American music to surge from this city in the preceding centuries - not least of which, Jazz, which calls the city its birthplace. Today, Congo Square is still a cultural meeting place and provides residents and visitors with a venue to share all kinds of music.⁷

PARLOR MUSIC

"A little music"--or--The delights of harmony by Jospeh Gillray (1810) gives us the impression that at-home music-making was not always an idyllic pastime …

Before recorded music, the only way to hear music was to attend someone else’s performance or play music yourself. This need meant that most households (especially of wealthier classes) had at least one or two family members who could be counted on to play or sing music. This at-home, amateur music-making was often encouraged in daughters and seen as one way to attract a future husband. Girls and women of early America were generally encouraged to play instruments that were considered more “feminine” due to the “softer” nature of the sound and the ability for a woman to look pleasant and pretty while playing. In this way, singing, piano, flute, violin, and harp were usually encouraged while brass (which necessitates a somewhat “puckered” face to perform), percussion, and cello (since one needed to hold it between one’s legs to perform) were usually discouraged. These gendered ideals of instruments are still a problem in modern society though trends are slowly changing.

At-home music was often performed in a PARLOR, a room in the house with a piano, space to perform, and space for guests or family members to sit and enjoy playing or listening to music together. This same room became the hub of the phonograph when it would later take hold in American households at the turn of the 20th century. A genre of music meeting the demands of at-home, amateur music-making developed that was often simple in difficulty, light in content, and meant to be pleasant in tone.

By the mid-1800’s, interest and prevalence in parlor songs increased due to the development of the LITHOGRAPHIC PRINTING PRESS (a type of mass-produced printing technique) that allowed music publishers to quickly produce thousands of copies of legible sheet music for sale. This made it easier for amateur musicians to collect libraries of music books and individual songs (think early singles) to perform at home.⁸ In addition to easier classical pieces for solo instrument, vocalist, or small chamber ensembles, other pieces with a more popular or “folksy” quality were in high demand.

One of these pieces was “A Perfect Day” by Carrie Jacobs Bond (1909) who composed the song to honor her friends while on a nature trip in California. The song would have been published in a variety of keys to make it possible for high, medium, and low voices to sing along with piano and different versions may have also included an additional instrumental accompaniment part (such as the cello alluded to on the sheet music in the video below).⁹

The Spirit of ‘76 - Archibald MacNeal Willard (1875)

MILITARY MUSIC

Outside the home, one place to hear live music was at military or civic functions. Since military music was most often an outdoor affair, the most common ensemble to hear performing military music was a MILITARY or MARCHING BAND which consisted of regiments of woodwinds, brass, and percussion in military uniforms and strict rows and columns whether they were marching or performing in a concert. The music performed by these groups were patriotic in nature including pieces of music from various wars, to marches, fanfares, and concert music written to honor government officials, visiting dignitaries, or commemorate civic events. Bands might be heard performing in a parade or at attention near the speaker’s podium at an important civic or governmental event.

In addition to playing at formal functions, military bands also had their place in actual wartime with FIFE (piccolo) and DRUM (usually a field drum which is like a deeper snare drum) or BUGLE (like a trumpet without valves) announcing the arrival of armies or signaling different directives during battle. Off the battlefield, wind musicians (including flute, oboe, clarinet, and bassoon) would often play more classical, popular, or folk-style music in the camps as a way to keep morale high and soldiers entertained between battles. This type of music for pleasure in military camps was known as HARMONIEMUSIK (a German term) and is the predecessor to the modern concert band.

John Philip Sousa’s “Stars & Stripes Forever” march - America’s official march.

Eventually, the popular format of the military band (both marching and harmoniemusik) detached itself from the government and civic bands were formed. This is most evident in the life work of JOHN PHILIP SOUSA who served as the director of “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band from 1880-1892 before establishing and touring with the Sousa Band - one of America’s most beloved touring ensembles at the turn of the 20th century. In addition to being America’s most popular military and civil band leader, Sousa was also a prolific composer. Hailed as the “American March King,” Sousa composed 136 marches in his lifetime including such patriotic favorites as “Stars and Stripes Forever,” and “Semper Fidelis.”¹⁰

MUSIC FOR THE THEATER

Theater music pre-recording era was much like the music of Europe. In fact, America was a little obsessed with keeping on trend with various musical offerings of Europe from opera to symphony orchestra and other entertainments. OPERA from European countries (especially Italy) was fashionable in America just as it was in Europe, even as operas by American composers struggled to be taken seriously. The METROPOLITAN OPERA, America’s premier opera company, was established in New York City in 1883. At first, the company was so enamored by Italian that it performed every opera in Italian - even the ones originally composed in German or French - but it eventually began to perform operas in their original language as well as operas by American composers. The Met is still in operation today though it continues to mostly perform older, classic works rather than contemporary operas.¹¹

Established even earlier in the same city, the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC is America’s oldest symphony orchestra and has been in operation since 1842. The Phil has performed under the baton of such celebrity conductors as Gustav Mahler, Arturo Toscanini, Leopold Stokowski, and Leonard Bernstein. In addition, the symphony has been the priviliged group to perform such world premieres as Antonin Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 “From the New World” (1893) and George Gershwin’s An American in Paris (1928). Today, it continues to be heralded as the best symphony orchestra in America and one of the top orchestras in the world.¹²

Jenny Lind, “The Swedish Nightingale” (1820-1887)

In addition to established ensembles, there were several musical celebrities of pre-recording age America including JENNY LIND, “The Swedish Nightingale.” Lind was a Swedish soprano and opera singer who transitioned from opera roles to a solo act career in 1849. In 1850, P. T. BARNUM (of Barnum & Bailey Circus fame) was able to work out an arrangement to bring Lind to the United States as her promoter on a tour of the country. Lind was a smashing success in the United States where classical music culture still strived for the recognition that America was as highbrow a music culture as Europe. But in addition to this “Euro-legitimacy,” Lind’s tour had the unexpected effect of bringing opera and classical music to the masses and her célébrité in addition to her earnest and sweet presence resulted in her becoming America’s first “sweetheart.” After Lind’s tour, the popularity of opera music as well as parlor sheet music and band arrangements would continue to surge for decades.¹³

Just as classical music was hitting a peak of popularity in America, a less scrupulous form of music known as Minstrelsy music was also being developed. Minstrelsy songs came about as a way for white Americans to attempt to interact with the music of Black enslaved and free people without actually forming relationships with the creators of this music. MINSTRELSY SONGS, therefore, were songs created by white composers and performers that approximated the form, rhythms, melodies, and performance styles of Black Americans during the mid-19th century.

An introduction to Minstrelsy *warning* images of actors in blackface.

Because these songs were inauthentic, unauthorized, and also created for comedy in addition to musical entertainment, they carried heavy racial undertones and discriminatory performance practices. Amongst these included white performers donning BLACKFACE (a performance technique that involves darkening skin with facial paint, wearing wigs, and donning other offensively over-exaggerated characteristics of 19th century Black Americans) and affecting a voice and speaking style that mocked Black Vernacular English). The musical numbers would be interspersed with other acts in a Minstrelsy Show - a type of variety show that included music, dance, comical skits, and talents - all performed by white performers in blackface for white audiences.

The most prolific composer of Minstrelsy songs was STEPHEN FOSTER who wrote such popular songs as “Oh, Susanna!,” “Camptown Races,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” and “Old Folks at Home” which continue to be beloved American “folk songs” with the words changed away from their originally racist Minstrelsy lyrics.

Eventually, Black performers began to perform in Minstrelsy Shows because they could make decent money due to the popularity of the genre - and light-skinned Black performers would even wear the makeup and other minstrelsy items of the white performers in blackface. Minstrelsy-style skits and musical numbers continued to be popular even into the television age and much of American musical theater production style finds its roots in the Minstrelsy shows.

TIN PAN ALLEY

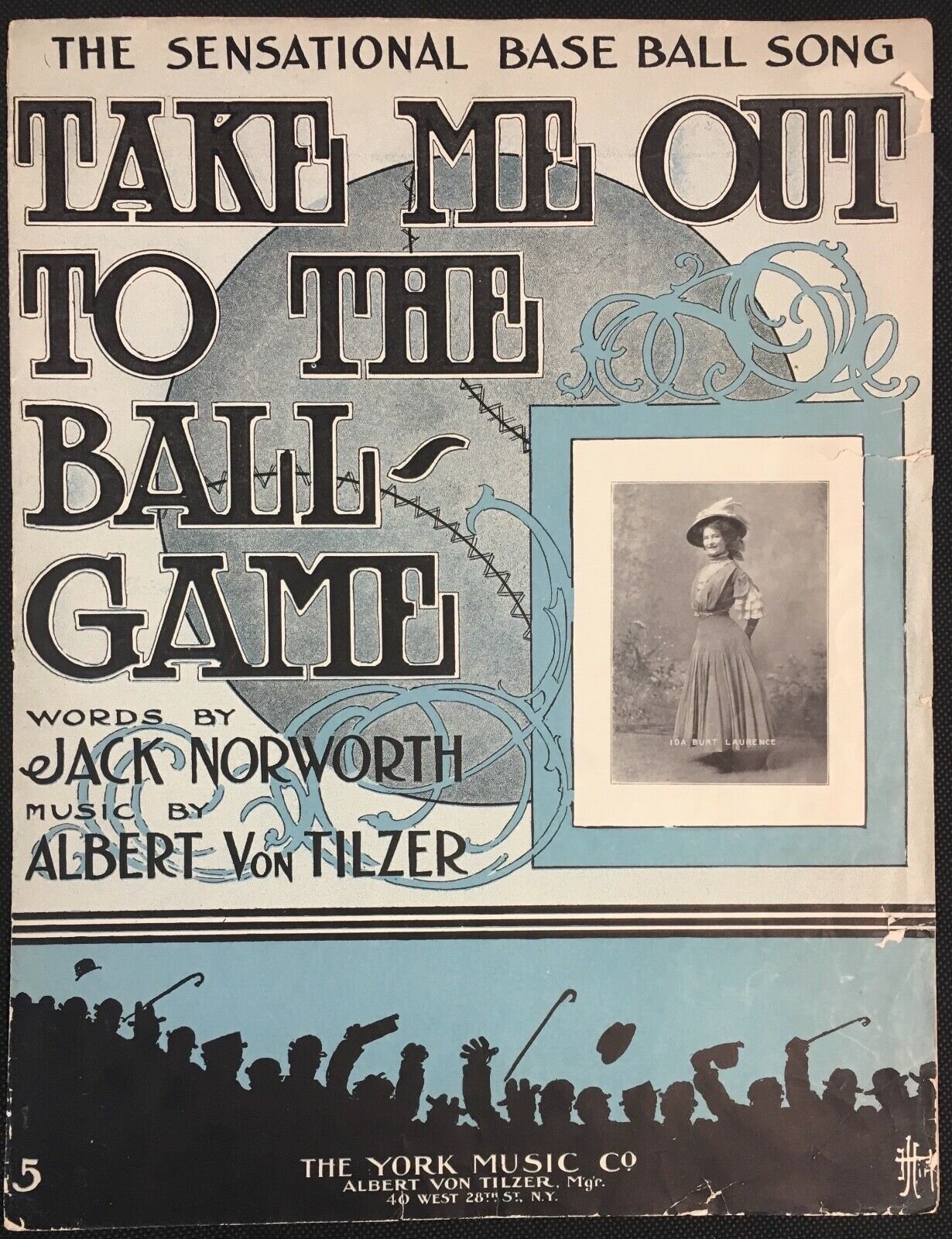

Sheet music for “Take Me Out To the Ball Game” (1908)

In the late 19th century, American sheet music publishing made it possible for music producers to start developing the first truly popular strain of music that wasn’t rooted in classical or folk traditions. The hub of this music production was centered on 28th Street in New York City between Broadway and Fifth Avenue (nicknamed “TIN PAN ALLEY” because of the cacophony of composers banging away at pianos writing the next hit song). Music from Tin Pan Alley music producers and composers tended to be short, fairly easy to play and sing by amateurs (remember this was pre-recording era), catchy and trendy. While most musicians and composers are inspired to create for art itself, Tin Pan Alley composers were out to maximize profits by writing quick, formulaic songs that they hoped would sell a million copies. Popular songs to come out of this time included “Give My Regards to Broadway,” “God Bless America,” “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” and “Sweet Georgia Brown.” Songs like “Yes, We Have No Bananas” are a reminder that many of the songs were NOVELTY SONGS - meant to be light and humorous rather than serious, heavy, or romantic.

RAGTIME

A precursor to Jazz, Ragtime music can be considered one of America’s very first unique popular genres. RAGTIME is a genre developed originally for piano (but later arranged for other instrumentations such as bands, orchestras, and chamber groups) that features a highly syncopated melody in the right hand (upper voice) with a left hand accompaniment called STRIDE that features alternating bass notes and chords. Ragtime was developed in Missouri (whereas most early musics were developed on the east coast like New York and New Orleans) and it is thought that the genre came about by pianists “ragging” simpler, more straight-forward pieces of music such as marches until the hard syncopation stood out. The fun, dance-inspiring music quickly gained popularity and sold much sheet music through the end of the 19th century. SCOTT JOPLIN was Ragtime’s most prolific composer, writing 44 rags as well as a ballet in Ragtime.¹⁴

“Maple Leaf Rag” - Scott Joplin (1899) as recorded by Joplin himself onto a player piano.

THE ADVENT OF RECORDING

Since the invention of the phonograph and recordable wax cylinders in 1877, much about music has changed. Certain styles evolved or died out while recording technology supported the birth and development of new genres. The practice of composing and performing music as well as what it meant to be a musician also changed. Following this week, every genre of American popular music we discuss will have been created after the availability to record music came into play. As you continue to learn about these music genres and their history, it is important to understand the context of how recordings altered the direction and speed to which music flowed.

Consider below some of the advantages and disadvantages of the invention of recorded audio.

ADVANTAGES OF RECORDING

Music became more accessible

Listening to music at all hours of the day

Listening to musicians in geographically and culturally diverse areas

Listening to musicians one can’t afford to see live

Listening to musicians one might not have been allowed to see or would have been socially frowned upon to see live (i.e. across racial or class lines)

The ability to listen to music in more intimate or individual spaces

Music accompanies other media (film, television, video game soundtracks, etc.)

Hearing a brilliant performance over and over

Capturing the sound of specific artists or important musical events (musicians, conductors, producers, festivals, performances, etc.)

A playback device can produce more continuous music than live musicians who will fatigue

DISADVANTAGES OF RECORDING

Decrease in live music performance

Decrease in live music attendance by audiences

Decrease in pay for *most* musicians

Decrease in amateur music-making

Raising the bar of what “sounds good” and establishing objective rubrics for subjective taste in music

Rigid expectations for how a piece or song “should” go

Music becoming more of a “background,” ambient soundtrack than listened to with intentionality

Most playback devices or environments do not offer the rich, organic quality of live music by acoustic instruments

Increase in commercialization and exploitation of music and musicians

Bottlenecking of genre, style, and demand for “superstar” artists at the expense of smaller artists

REFERENCES

1. “Guide to Native American Music.” 2012. World Music Network. https://worldmusic.net/blogs/guide-to-world-music/guide-to-native-american-music

2. “Singing Schools.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/collections/music-of-nineteenth-century-ohio/articles-and-essays/singing-schools/

3. “Lowell Mason.” 1998. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lowell-Mason

4. “William Billings.” Songwriters Hall of Fame. https://www.songhall.org/profile/William_Billings

5. “Shape Note Singing.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/collections/songs-of-america/articles-and-essays/musical-styles/ritual-and-worship/shape-note-singing/

6. ”Banjos.” Smithsonian Music. https://music.si.edu/spotlight/banjos-smithsonian

7. Branley, Edward. 2012. “NOLA History: Congo Square and the Roots of New Orleans Music.” https://gonola.com/things-to-do-in-new-orleans/arts-culture/nola-history-congo-square-and-the-roots-of-new-orleans-music

8. “Printing & Publishing of Music.” The Parlor Songs Academy. http://parlorsongs.com/insearch/printing/printing.php

9. “A Perfect Day.” Song of America. https://songofamerica.net/song/perfect-day/

10. “John Philip Sousa.” The United States Marines Band. https://www.marineband.marines.mil/About/Our-History/John-Philip-Sousa/

11. “Our Story.” The Metropolitan Opera. https://www.metopera.org/about/the-met/

12. “History.” New York Philharmonic. https://nyphil.org/about-us/history

13. “Jenny Lind.” 1998. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jenny-Lind

14. “History of Ragtime.” Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200035811/