BINARY FORM AND

THEME & VARIATION

This page is a supplement to The Complete Musician: Chapter 20 - Binary Form and Variations

BINARY FORM

Up until now, we have been studying snapshots of sound like pitch, rhythms, and chords; and phrases and periods consisting of melodies and chord progressions. We will now zoom out one view further to examine simple, short musical forms starting with Binary Form. BINARY FORM is a short piece of music (or a short section of music within a larger work) that has two complimentary and usually equal-length sections which usually both repeat. The first repeated chunk is called A and the second repeated chunk is called B because that is how the alphabet works. Notice that they are capital letters? That is important. Always label the major section of forms with capital letters. Before we get into how binary form works, let’s enjoy this piece in binary form.

Now let’s keep track of a word bank of key definitions because there are a lot of types of binary forms:

MELODIC REFERENCE

SIMPLE: The A and B melodic material are completely different (B does not call back to A). ||: A :||: B :||

ROUNDED: The B section includes a call back to A. This can occur during the same length of time as the original A (so the second section only calls back to some of A) or the length of the B section may be extended to include all new B material plus all the original A material. ||: A :||: B A :||

In rounded binary, the B material is referred to as a DIGRESSION because it digresses momentarily from the overarching A material.

HARMONIC REFERENCE

SECTIONAL: Both the A and B sections end with the tonic of the key (they are complete without the other). ||: … I :||: ... I :||

CONTINUOUS: The A section does not end on tonic and the B section does not begin on tonic (they are connected). ||: … V :||: … I :||

BALANCED: The end of B is identical to the end of A (if they’re sectional and both ending in tonic) both melodically and harmonically -or- if continuous, the end of B is referencing the end of A but doing so in the tonic so it feels like an ending - both the melody and harmony mirror A but finish in tonic.

LENGTH REFERENCE

SYMMETRICAL: Both the A and B sections have the same number of measures (like A is 8 measures and B is 8 measures).

ASYMMETRICAL: The two sections are different lengths - usually B is longer than A. Asymmetrical binary form is much more common in rounded form since the second half will often include a complete B and complete A statement.

BINARY EXAMPLE 1

Look. Listen. Look and listen to this folk tune, Jacky Tar, and decide what kind of binary it is in. This is called a “lead chart” which is popular in folk music and jazz. You only see the very basic-most frame of the melody and the chords. The musicians then add ornamentation and improvisation to the melody and come up with a chord comp based on the style and tempo they’re performing.

Is it Simple or Rounded? Sectional or Continuous? Is it Balanced? (Does it need to be balanced?) What about Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical? When you think you have it, remove your head and turn it upside down so you can read the answer below …

ʎɹɐuᴉq lɐuoᴉʇɔǝs ǝldɯᴉs lɐɔᴉɹʇǝɯɯʎs

BINARY EXAMPLE 2

Next up is Amy Beach’s Gavotte No. 2 from her Opus 36. Based on the material happening in each repeated section, decide what type of binary form this is: Simple or Rounded? Sectional or Continuous? Is it Balanced? What about Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical?

Girl could rock an updo …

AMY BEACH (1867 - 1944) was an American composer and pianist. She was married at 18 but widowed by 33 and spent the remainder of her life supporting herself as a composer and performer and was part of the Second New England School of composers.

ʎɹɐuᴉq lɐuoᴉʇɔǝs pǝpunoɹ lɐɔᴉɹʇǝɯɯʎs

BINARY EXAMPLE 3

Here is a minuet from 1779 by composer Ignatius Sancho. Using the method above, determine what type of binary form it is. Simple or Rounded? Sectional or Continuous? Is it Balanced? What about Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical? Answer is below Sancho’s bio, upside down.

Minuet No. 4 (0:00 - 0:58)

Those eyes, tho …

IGNATIUS SANCHO (1729 - 1780) was an English composer, writer, and actor born as an enslaved person aboard a ship from Africa to South America. Orphaned, he was sent to England where he learned to read and ran away. His book, The Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African, was the first to be published by a formerly enslaved person.

ʎɹɐuᴉq snonuᴉʇuoɔ ǝldɯᴉs lɐɔᴉɹʇǝɯɯʎs

THEME AND VARIATION

Maybe the laziest way to compose an extended piece of music (but also quite rewarding for your audience because they can feel super smart without having to work very hard) is to use the THEME AND VARIATION form. In this form, a THEME (either a single phrase, period, or some configuration of phrases) is presented in one key and style. For the remainder of the piece, all new material is a VARIATION of the original theme, with elements altered such as rhythms or notes in the melody, harmony, texture, tonality, meter, or style and expression. Very basic theme and variation just looks like: A A’ A’’ A’’’ A’’’’ etc. but more complex theme and variation could include introductions and transition material between the variations and each variation might be a different length. Theme and Variation form pieces are broken up into two categories:

SECTIONAL VARIATIONS: The theme and each new variation are presented as a detached complete miniature, usually ending in tonic, often with a double bar line before the next. Sectional variation usually has the most dramatic evolution between variations and no transitional material between. You will see the sectionalization present with each variation labeled VAR. I, VAR. II, etc. almost as if they are separate movements of the piece - and there will be a moment of silence between.

CONTINUOUS VARIATIONS: The theme and each new variation are blended together more seamlessly with transitions between or preparation for the new variation in the previous variation’s ending. Continuous variation pieces often have shorter themes and less dramatic sectionalization between movements. Because continuous variation is a bit more difficult to construct, it tends to follow more rigid structures. One element that helps to tie each variation together is the use of OSTINATO in one of the following ways:

OSTINATO: A repetitive elemental idea that continues in a piece of music even as other elements change.

GROUND BASS: A repetitive bass line in a piece of music.

CHACONNE: A repetitive chord/harmonic structure in a piece of music.

PASSACAGLIA: A repetitive bass line and chord/harmonic structure in a piece of music.

Canon in D - Johan Pachelbel (Ground Bass)

Suite No. 1 in E-flat: I. Chaconne - Gustav Holst

Partita for 8 Voices - IV. Passacaglia - Caroline Shaw

ENIGMA VARIATIONS

Let’s take a look at a very popular theme and variation piece in the classical canon: English Romantic composer Edward Elgar’s Enigma Variations (1899). It is a theme and fourteen variations for orchestra and it lasts approximately 38 minutes. Each variation is meant to capture the personality of a close friend or family member (isn’t that so cute?).

Additionally, the unknown “enigma” of the variations is that there is apparently some larger “theme” to the entire piece, that “goes but is not played” that Elgar never revealed. If you enjoy musical mystery, check out some theories on what the enigma might be HERE.

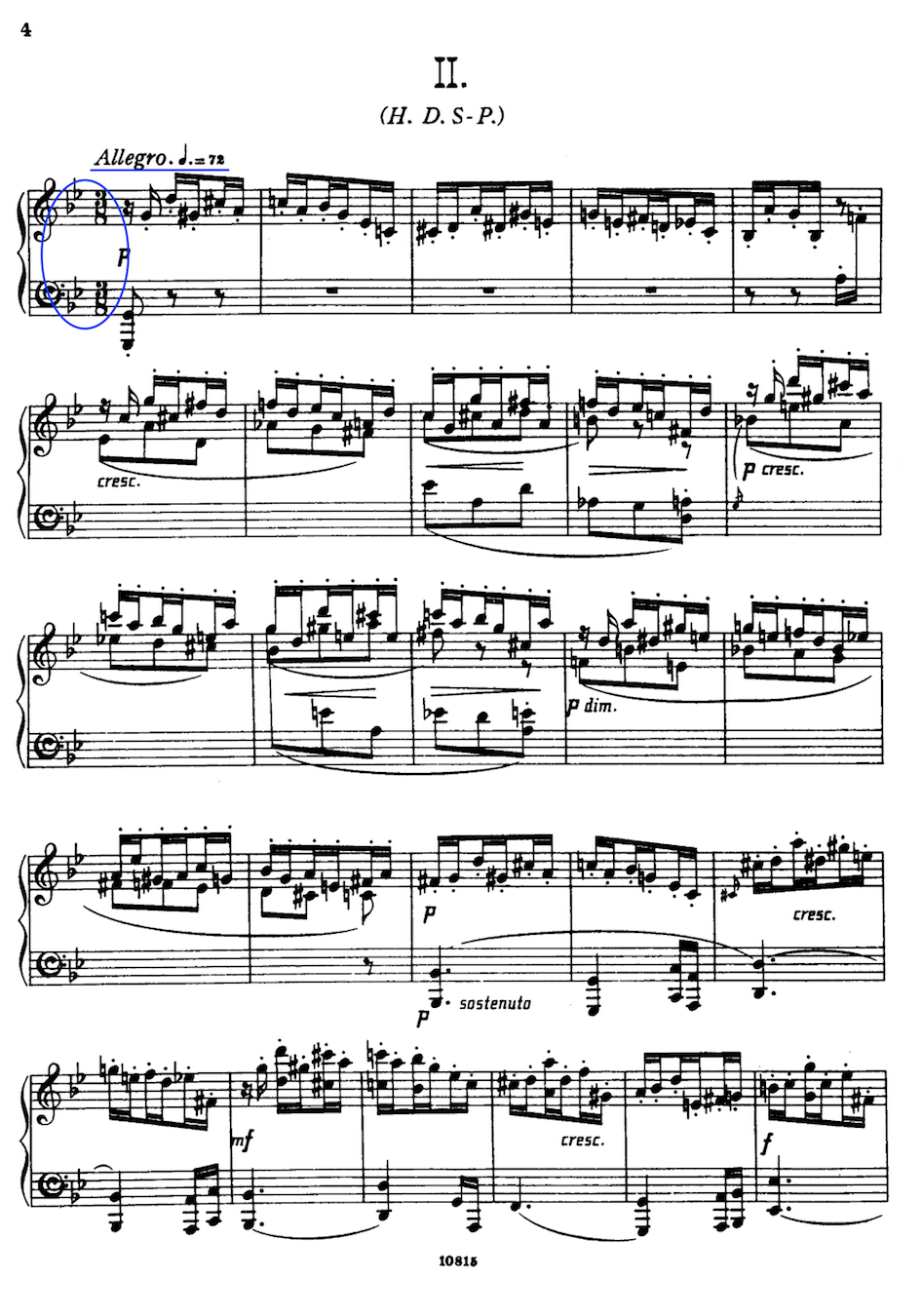

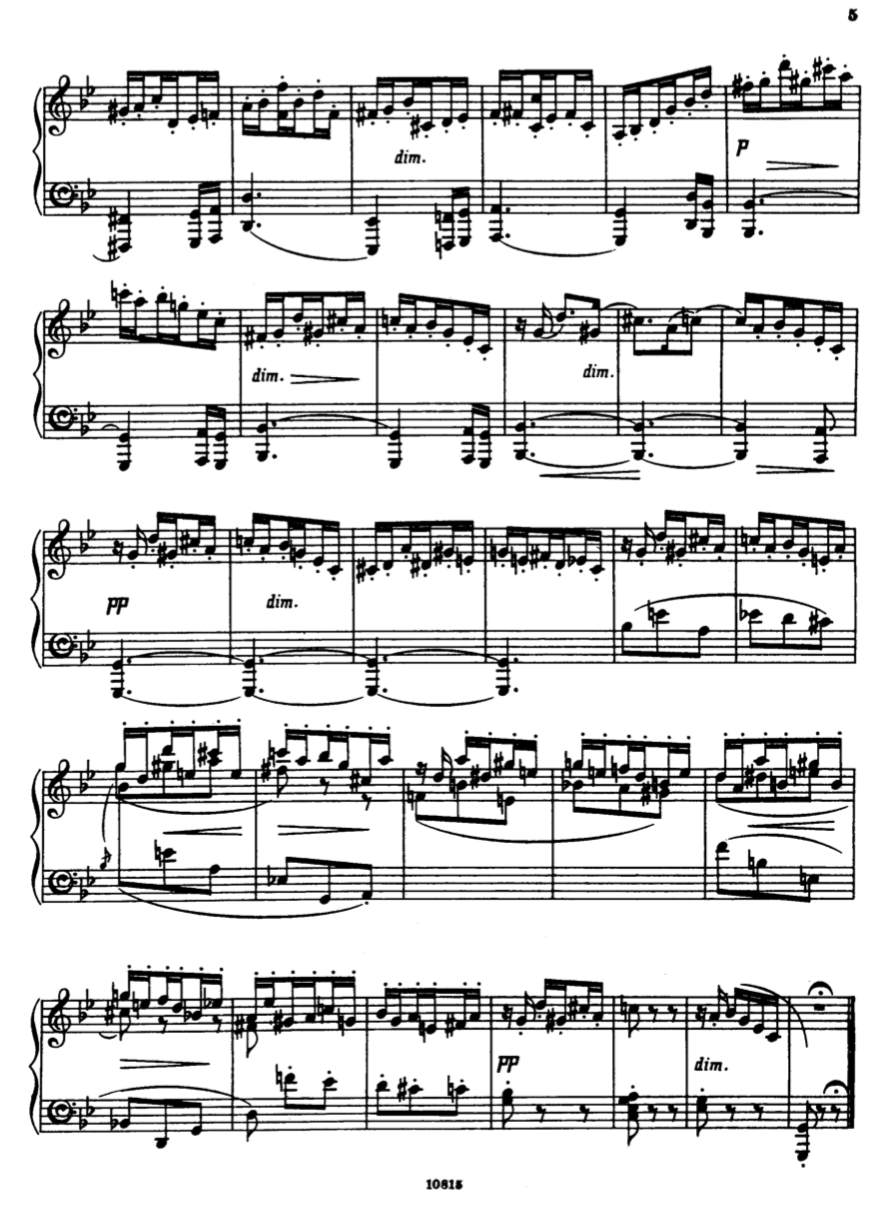

We’re going to dig into the theme and the first two variations and discuss their similarities and contrasting materials. For the sake of simplicity, we will be looking at a PIANO REDUCTION (where the whole orchestra has been simplified down to one piano score).

Edward Elgar (1857 - 1934): Winner of the Best Mustache Award every year

THE THEME

Theme (Andante) 0:00 - 1:59

The theme begins in a slow, expressive sostenuto in G Minor with the middle phrase in the parallel major (G Major). The melody is in the soprano voice (violins and clarinets) and the accompaniment is purposeful, even a bit plodding, with movement almost entirely on 1s and 3s of each 4/4 measure. The 17-measure movement finishes on a G Major chord (PICARDY THIRD) and sustains over into the next variation. This is an example of CONTINUOUS VARIATION since there is not a stark separation between the sections.

VARIATION I

The first variation is in the same tempo (L’ISTESSO means “the same”), time signature (4/4), and tonality (G Minor) as the theme. The biggest change in this variation is the MELODY, TEXTURE and LENGTH. The more chromatic and busier melody doubles octaves and moves from instrument to instrument more frequently than the theme. The bass line becomes more energized with eighth note movement and larger leaps. Above, an OBLIGATO (higher countermelody) is added to respond to the melody and thicken the texture.

Regarding the length, there is a two measure introduction and each of the three phrases of the theme have more material added on to extend them - including cadencing in major at the final phrase.

Heavier articulations (accents) and contrasting dynamics are used toward the end of the variation (second page) to heighten the drama.

This variation ends in the SECTIONAL style of theme and variation as there is a huge shift in variation into Variation II …

VARIATION II

In VARIATION II, almost everything is different. In fact, the only thing that stays the same is the G Minor tonality.

The tempo increases to a dotted-quarter = 72 bpm and the whole feel of the variation is much faster since the melody is moving at eighth notes. Sixteenth notes in the moving accompaniment create a sense of driving urgency throughout. The time signature is in 3/4 so there is a triple feel to the movement rather than duple/quadruple like in the previous two.

This movement is highly chromatic with many notes out of the key signature. The low melody begins in the basses and celli in octaves in the 18th measure (so the first 17 measures are just setting the stage).

Instead of finishing dramatically and succinctly as in the first two section, Variation II dribbles out on sixteenth notes at pianissimo volume and there is a fermata’ed rest denoting (an uncomfortable?) space and silence.