Let’s begin by watching the following video. Indian Classical Music probably sounds somewhat familiar to you in that you have heard it or music similar to it before. As you watch the video, consider some things:

Where have you heard this type of music before?

Do you associate it with a specific place/culture/people/setting?

What purpose might this type of music serve?

In this video specifically: what types of instruments are you hearing? How are they similar or different from instruments you are more familiar with? What about the music itself? What is striking you about the Rhythm/Melody/Harmony/Timbre/Dynamics/Texture/Form of the music that gives Raag its unique quality?

CARNATIC VS. HINDUSTANI MUSIC

The music of the Indian subcontinent (located in Asia) is divided into the larger territory of HINDUSTANI (Northern) music and CARNATIC (Southern) music. Carnatic music is the older practice. Hindustani music has been influenced by Persian colonists who occupied the region of northern India in the 16th century and blended their music traditions with those of the original Indians. Hindustani music is based on Carnatic but has many differences. Hindustani music is more similar to Western Classical Music and has a more concert-based, performance history where longer pieces are prized while Carnatic music is more closely connected to religious and cultural activities and features shorter pieces. Hindustani music has a longer tradition of IMPROVISATION (making up music on the spot).

In addition to these two traditions, there are mainstream genres such as Pop and Bollywood that are more nationally consistent and carry elements of both.

राग WHAT IS RAAG?

RAAG (also called RĀGA or RAGAM) is a set of notes (SWARAS स्वर) arranged in an ascending (rising in pitch) and descending (lowering in pitch) order. The seven main pitches used are:

Types of Ragas (click through the video to watch on YouTube)

SA shadaj (षड्ज)

RI rishabh (ऋषभ)

GA gandhar (गान्धार)

MA madhyam (मध्यम)

PA pancham (पञ्चम)

DHA dhaivat (धैवत)

NI nishad (निषाद)

Unlike most Western Classical Music scales, Raag often use different notes on the way up and the way down. Also unlike Western scales, Raag have specific combinations of notes that must always be performed together and one cannot compose using any combination at any time. These combinations are called CHALAN. Different Chalan rules can exist for the same sequence of scalar notes, resulting in multiple different Raag for the same set of notes.

AAROHA: ascending order of notes

AVAROHA: descending order of notes

JAATI: categories of Raag based on how many notes are in the scale

Each Raag creates a mood called a RAS that conveys a story or emotion to the audience. Different Ras types include tranquillity, devotion, love, loneliness, pathos, and heroism. In addition, Raag are associated with different times of the year and day.

Raag are not scales because they are more structured than scales. Raag are not melodies (songs) because they are less structured than songs and songs are. If this concept seems difficult to understand, it is because there is no parallel phenomenon in Western music or culture to compare Raag to.

राग RAAG DEFINED …

The word RAAG and its anglicized variations is ancient Sanskrit for “color,” “dyed,” or “passion.” The combination of these definitions gives us a true sense of what Raag represents in classical Indian culture: a musical heritage that acknowledges music’s (and specifically musical scales’) power over the human spirit. The idea of Raag is that each scale has a mood that directly relates to a human emotion.

Raag are used for prayer and meditation music in many Indian religions including Hinduism, Sikhism, and Sufism. In Hinduism, it is believed that Raag are naturally occurring scales that are not invented or created by musician, but rather discovered and gifted to humanity by deities.

Raag are referenced in many religious texts of India including the Bhagavad Gita which dates back to c. 200 B.C.E.

ताल WHAT IS TALA?

TALA is the concept of rhythm or musical meter in Indian Classical Music. LAYA is the more general term for rhythm occurring in nature. Tala are often metered out by hand clapping, knee patting, or another physical gesture made through body percussion. Unlike most Western Classical Music, the rhythmic meter of India is often uneven, resulting in a different number and emphasis in each “measure” or section of a given rhythmic pattern. Just like Raag, Tala have many named and learned patterns that an Indian Classical musician can incorporate into their musical performance. In the Carnatic tradition, the most popular Tala is ADI TALA (आदि ताल) which is eight sets of four. The most popular Tala used in Hindustani music is TEENTAL (तीन ताल) which is four sets of four.

Konnakkol Duet by Vidwan B R Somashekar Jois and Kumari V Shivapriya

Mind-melter for math nerds …

INSTRUMENTS

Indian Classical Music (both Hindustani and Carnatic) includes string, percussion, and wind instruments in addition to the voice. Specific instruments are associated with one region or another.

सितार SITAR

The SITAR is a hollow gourd and wooden string instrument. It is played seated and plucked by the performer’s fingers. It has 18-21 strings. 6-7 are played by the musician while the rest are strung under the fingerboard. These SYMPATHETIC STRINGS vibrate along with the strings that are being played for a natural drone under the entire performance. It is used more often in Hindustani music than Carnatic. The timbre of the sitar is ethereal, delicate, and shimmery.

तानपूरा TANPURA

The TANPURA is a hollow gourd and wooden string instrument. It has four strings and only plays DRONES (open string notes that do not change). The drones create a meditative texture under another instrument or voice when performing the melody. The drone pitches are based on what Raag is being performed. This is considered an accompaniment instrument. The timbre is warm, rich, and shimmery.

वेणु SHEHNAI

The SHEHNAI is a wind instrument and the Indian equivalent to the Oboe. It includes a wooden body, a metal bell, and a double reed that the performer blows into. It is closely associated to weddings and temple ceremonies in Hinduism and plays melody. The timbre is nasal, penetrating, and intense. The Shehnai is found more in Hindustani music while the Nadaswaram is a similar double reed instrument used in the Carnatic tradition.

स्वरन्धरा HARMONIUM

The HARMONIUM is a pump organ. It is essentially a keyboard accordion with an attached bellow (like a fireplace bellow) that pushes air over organ reeds. In this way, the Harmonium is a wind instrument because it utilizes wind, but it is a keyboard instrument in how the notes are struck and performed. The Harmonium is found more in Carnatic music and plays melody, not chords and harmony like you might hear from a European accordion. The timbre of the Harmonium is pure, thick, and focused.

तबला TABLA

TABLA are a pair of drums that create the rhythmic backbone in most Indian Classical Music. The smaller drum (right-hand or dominant) is made of wood and the larger drum (left-hand or subdominant) is made of metal. They both have skin drumheads attached to the drum with rawhide cord. Each drum also has a small circle of rice paste on the top which serves to deaden the drumhead, making the rhythm sound more pronounced and accurate. The Tabla’s timbre is hollow, ringing, and cool.

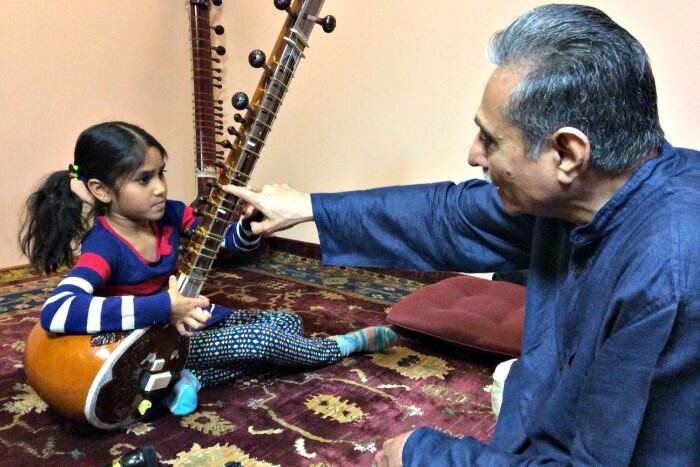

गुरु शिष्य GURU-SHISHYA TRAINING

Similar to Taiko, Indian Classical Music is taught in an oral tradition with masters (called GURU in India) training their students directly. This method is known as the GURU-SHISHYA or “master-disciple” school of training where each student can trace their lineage (PARAMPARA) back through great masters of the art. Guru-Shishya is a common form of education in India for religion and many of the arts including yoga.

Disciples will often live at their guru’s home, being treated like members of the family while they study with their teacher. A quality master-disciple relationship is developed through the genuineness of the guru and the obedience and openness of the disciple.

MUSICAL ELEMENTS OF INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC

RHYTHM: Rhythm in Indian Classical Music is very complex, following the system of Tala developed over many centuries. The sense of meter, tempo, and subdivision exists as in Western music, but the meter is often asymmetrical and the rhythmic phrases much longer than Western music. In addition, there is a stronger connection to the body with rhythm being performed with body and vocal percussion much more often than in Western music.

MELODY: Melodies are complex and improvised in the Hindustani tradition while mostly pre-composed in the Carnatic. They are based off Raag - a series of pre-established notes and sets of notes that a musician can use to develop a melody. Melodies are usually much longer than Western Classical melodies and do not follow the same symmetrical formula.

HARMONY: The Western understanding of harmony is not prevalent in Indian Classical Music. This is because a good deal of the music is based on the melodic development of a raag which, via improvisation, would be challenging/unpredictable to set harmony to in the moment. In addition, when multiple melodic voices are present, they perform in unison or heterophony, so harmony is not established. The closest thing to harmony found in Indian Classical Music is the concept of DRONE. Drone is an English word for the phenomenon of a sustained pitch or pitches (usually low in range) under a melody. Drones are heard in Indian Classical music in the form of the sitar (which includes sympathetic strings that vibrate even when not actively plucked) or bowed string instruments. This is similar to how a bagpipe (in Scottish music) plays a sustained pitch out of all of the pipes of the instrument except the one the player fingers.

Example of Indian vocal timbre

TIMBRE: Indian Classical Music has a variety and complexity of timbres. One that is especially different from Western Classical Music is the treatment of voices. In Western music, voices can be breathy or full and often utilize vibrato. In Indian music, the voice is meant to always sing clear and full with no vibrato or use of FALSETTO (head voice when Westerners sing high in their vocal range). Also, there is a noticeable nasally timbre prized in many of the great Indian Classical singers.

DYNAMICS: Dynamic contrast is generally not an important proponent of Indian Classical Music. Much of the music is soft and reflective and other music is loud and more boisterous, but generally, a single piece of music sticks to one volume throughout to accompany the mood that is being developed via the raag.

TEXTURE: The texture of Indian Classical Music is very simple in comparison with other traditions around the world. This tradition is not constructed in the Western Classical Music concept of harmony and therefore does not carry the styles of texture associated. Instead, most performances of Indian Classical Music involve one melodic instrument with or without percussion which does not count as a texture element as it is non-melodic. These performances would be considered solo monophonic. When more melodic voices are added, the texture becomes monophonic unison (all voices performing the same line together) or heterophonic (all voices performing a line with some voices adding in more notes or rhythms.)

FORM: The structure of Indian Classical Music is not as formulaic or symmetrical as Western Classical. It is based on the combination of Raag and Tala as well as the musicians’ improvisation and collaboration skills between performers. There is not meant to be repetitive patterns in the way Westerners are used to hearing music but, instead, the development of Raag and Tala over time heighten the emotional connection of audience members to the music.

COSTUME

There is no set uniform for Indian Classical Music performers but most will wear traditional Indian clothing (and it is, indeed, what many people in India still wear in daily life). This can include SAARI (wrap dress) or SALWAAR KAMEEZ (a dress with trousers) for women and KURTA (a long shirt with trousers) or ANGARKHA (a long fitted jacket with trousers) for men. The dress of the performer is not important.

FAMOUS INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSICIANS

Indian Classical Musicians are known as being great soloists, collaborators, and teachers. Unlike in Western music, there are not set, touring ensembles who always perform together. Instead, various vocalists and instrumental performers will arrange to perform together for one or multiple collaborations (sometimes collaborating often and regularly) or in solo acts.

Ravi Shankar (1920-2012)

RAVI SHANKAR (1920-2012) is considered the most well-known Indian Classical Musician in the world. He was a leading Sitar Guru (earning the title “Pandit” or “Master”) and collaborated with many international musicians including The Beatles and other pop artists as well as classical symphonies around the world.

He is the father of both Norah Jones, a Grammy Award-winning American singer-songwriter, and Anoushka Shankar, one of the world’s current leading sitar players.

Other famous Indian Classical Musicians include KUMAR SHARMA (santoor player), HARIPRASAD CHAURASIA, (bansuri flute player), ZAKIR HUSSAIN (tabla player), MS SUBBULAKSHMI (Carnatic singer), and ANOUSHKA SHANKAR (sitar player).

While not a strict Indian Classical Musician, composer A.R. RAHMAN has done much to incorporate Indian traditional music into pop and film settings such as his score for the film, Slumdog Millionaire.

WHERE TO HEAR INDIAN CLASSICAL MUSIC IN THE USA

Indian Cultural Festivals and Community Centers

Performed in Touring Concerts

Hindu and Sikh temples

College Campuses

In some Bollywood movies (although most of the music in Bollywood movies are pop-based)

Some Indian Restaurants