KEY SIGNATURES, CIRCLE OF FIFTHS & MINOR SCALES

INTRODUCTION

Now that we understand major scales and their construction, we can read and compose music using any of the 12 major scales we identified last week. Let’s take the B Major scale for example: B C# D# E F# G# A# B. If we wanted to compose a song using this scale, we would just place notes from the scale in an order and rhythm of our choosing. But wouldn’t it be annoying (not to mention cluttered and a bit hard to read) if we had to label all five sharped notes every time we used one? YES! That’s where KEY SIGNATURES come into play …

KEY SIGNATURE

A KEY SIGNATURE is a collection of sharps or flats (or, on rare occasions, naturals or sharps and flats) between the clef and the time signature on a musical staff before the first measure of the piece begins. This tells the musician what scale the piece has been composed in and what sharps/flats/naturals to use when playing. By reading what and how many accidentals are in a piece before it begins, you will know what key the piece is in.

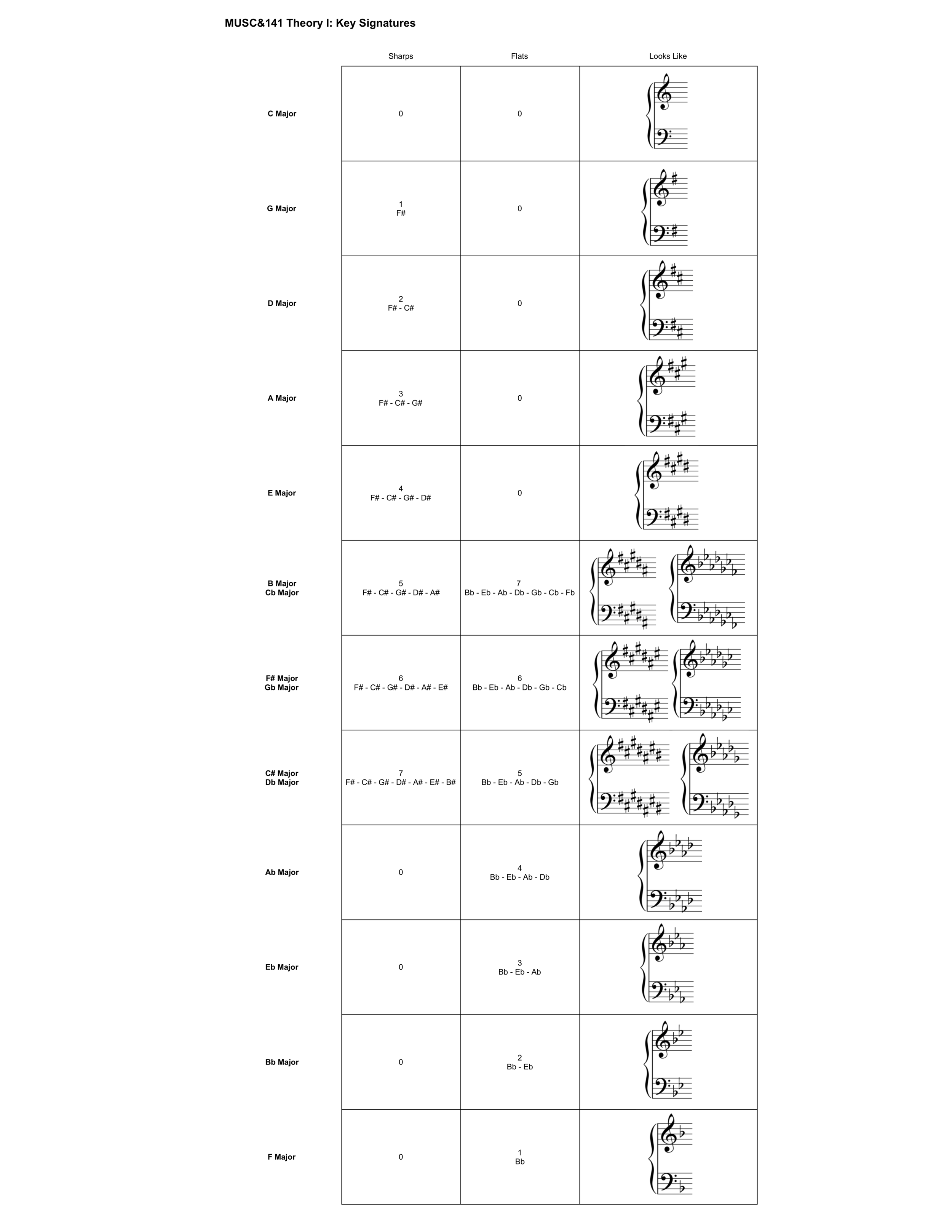

Major keys have only sharps and naturals or only flats and naturals, never sharps and flats. Below is a table of how each key looks and what sharps or flats you can find in them. Note that the keys B/Cb, F#/Gb, and C#/Db are ENHARMONICS of each other - so while these are just 3 audible scales, there are two ways of writing each of them depending on which enharmonic root you start with.

IDENTIFYING & BUILDING KEY SIGNATURES

It’s important to know how to build/identify a scale based on a given key signature and the opposite skill of building/identifying a key signature if you are told the root of the scale. Below are four constants of Western Music Theory to memorize which will help you with all your work in theory moving forward …

Order of sharps

Sharps always appear in a specific order starting with F#. Whenever you add a new sharp to a key signature, you always keep all the previous sharps. The order of sharps is:

F# - C# - G# - D# - A# - E# - B#

You can memorize this order of sharps with the mnemonic device: Fat Cats Go Down Allies Eating Burritos

RULE of sharps

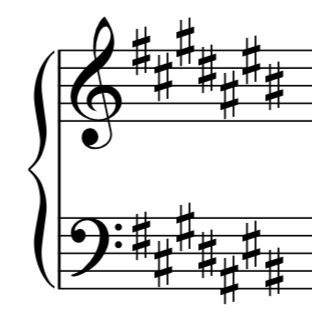

You can figure out what scale a piece was composed in by looking at the key signature. To do this, you find the last sharp in order (left to right, not bottom to top), then go one half-step higher. Whatever that note is will be the root of the major key. So in this example, the last sharp in order is B# and a half step above that is C#, so this piece will be in the key of C# Major.

Order of FLATS

Flats always appear in a specific order starting with Bb. Whenever you add a new flat to a key signature, you always keep all the previous flats. The order of flats is:

Bb - Eb - Ab - Db - Gb - Cb - Fb

You can memorize this order of flats with the mnemonic device: BEAD Greatest Common Factor (like in math)

RULE of FLATS

You can figure out what scale a piece was composed in by looking at the key signature. To do this with flats, you find the second to last flat in order (left to right, not bottom to top). Whatever that note is will be the root of the major key. So in this example, the second to last flat in order is Cb, so this piece will be in the key of Cb Major.

A NOTE ON ACCIDENTALS IN KEY SIGNATURES …

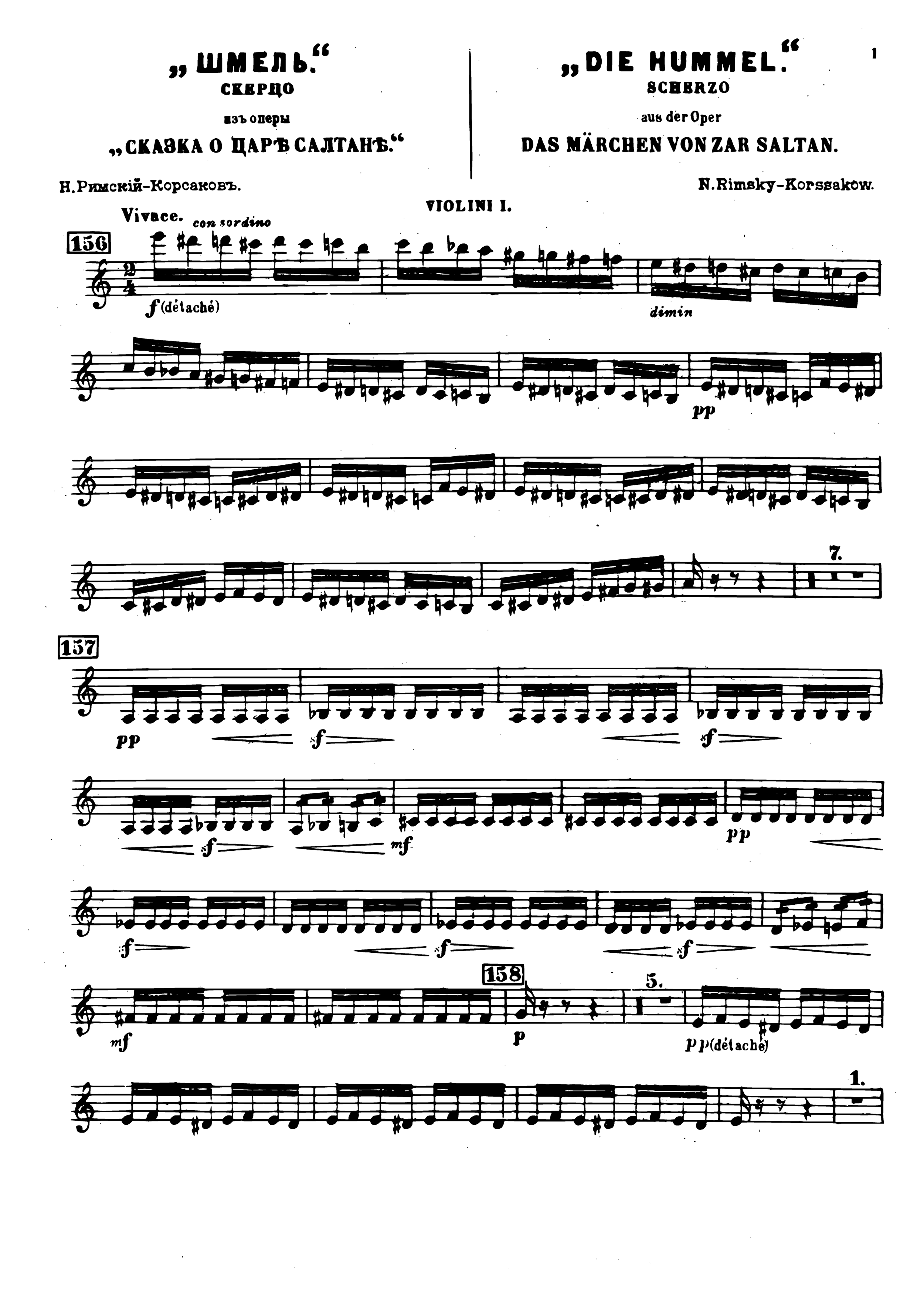

Plenty of pieces aren’t in just one key signature. In order to access all the notes outside of the closest key signature, a composer will use ACCIDENTALS (sharps, flats, and naturals) outside the key as the piece moves along. The rule of accidentals in music is that an accidental applies to the note the first time it is marked in a measure and every other instance in that measure. Upon a new measure, the note reverts to its key signature version until acted upon by another accidental. An exception is if an accidental note is tied to a new measure. The note will retain the accidental through the tie but revert to the key signature version once the tie releases.

Accidentals can be “canceled out” within a measure by the introduction of a new accidental to the same pitch. In general, accidentals don’t apply to different octaves of the same note, though there are debates on this concept.

Check out Nikolai Rimsky-Korsokov’s 1900 “Flight of the Bumblebee” - the key signature has no sharps or flats so all of them must be added as accidentals each measure.

“Flight of the Bumblebee” Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1900)

CIRCLE OF FIFTHS

All key signatures are interconnected and can be visually compared using a diagram called the CIRCLE OF FIFTHS. This diagram is called the Circle of Fifths because it is in the shape of a circle that moves up a fifth by root position as it turns clockwise. Conversely, it moves down a fifth (or up a fourth) by root position as it turns counter-clockwise. The counter-clockwise relationship in this diagram is called the CIRCLE OF FOURTHS. The Circle of Fifths shows (from outside to inside each segment) the KEY SIGNATURE, MAJOR KEY, and MINOR KEY (discussed below) associated with each. The circle begins at “0” sharps or flats in the 12 o’clock position then adds one sharp with each turn to the right and one flat with each turn to the left. The bottom three keys (5, 6, and 7 o’clock) show the two ENHARMONIC keys for each position.

MINOR SCALES

Take a listen to the Seattle Symphony and conductor Thomas Dausgaard performing Edvard Grieg’s In the Hall of the Mountain King from his ballet suite, Peer Gynt (1875).

This short ballet movement is not in a major key. It is spooky, scary, and aggressive sounding. You also can’t sing a major scale’s solfege to it. Instead of singing Do-Re-Mi, you would need to sing Do-Re-Ma. The Ma replaces Mi because scale degree 3 is one half-step lower than normal and has become a b3 (“lowered 3rd”). The opening of the melody in solfege goes: “Do Re Ma Fa Sol Ma Sol”.

In the Hall of the Mountain King is a piece in a MINOR KEY that uses a MINOR SCALE. Let’s look at the first page of the score ….

If you look at the non-transposing instruments (Flauto/Flute, Oboi/Oboe, Fagotti/Bassoons, Violoncelli/Cellos, and Bassi/String Basses), you see a key signature of two sharps: F# - C#. The two-sharp key signature is normally D Major but when you look at the actual melody (and other parts), there is a lot of emphasis on the notes B and its fifth, F# (not D and its fifth, A) in addition to it not sounding major.

This is because In the Hall of the Mountain King is in B MINOR, a key related to D Major because it shares the same key signature, but the melodies and harmonies are based around the root of B. The notes used for this piece (with a few other accidentals) are:

B - C# - D - E - F# - G - A - B

We call this the key of B NATURAL MINOR because it naturally occurs when you take the key signature of D Major and play it starting on scale degree 6. There are other minor modes, as well, that we will learn about below.

Natural minor scales can be thought of in two ways: based on the PARALLEL MAJOR SCALE (a major scale that starts on the same root) or based on the RELATIVE MAJOR SCALE (a major scale that shares the same key signature).

Parallel major/minor

B MAJOR SCALE: B - C# - D# - E - F# - G# - A# - B

SCALE DEGREES: 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 - 1

B MINOR SCALE: B - C# - D - E - F# - G - A - B

SCALE DEGREES: 1 - 2 - b3 - 4 - 5 - b6 - b7 - 1

(we say “lowered 3rd,” “lowered 6th,” and “lowered 7th”)

*these keys are PARALLEL because they begin on the same first scale degree

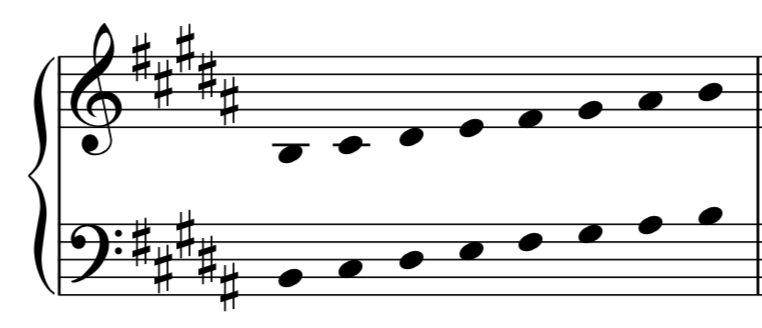

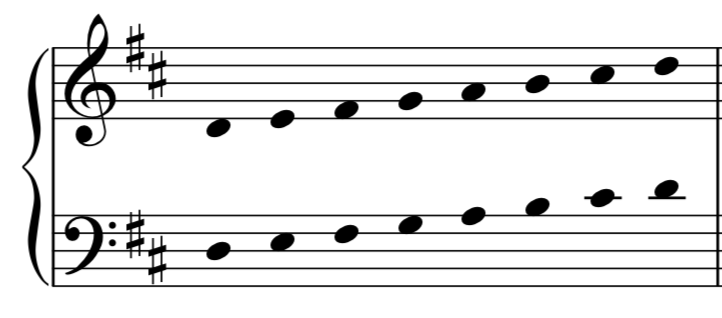

B Major

B Natural Minor

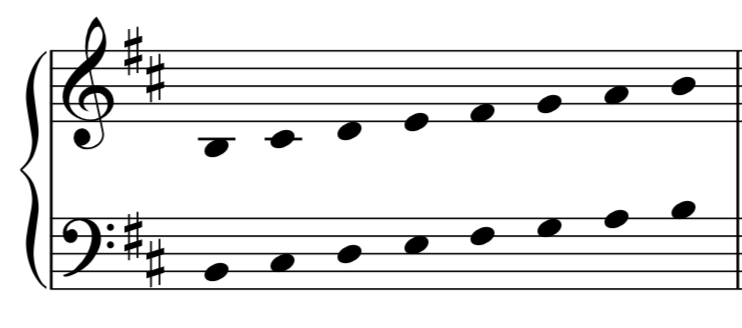

RELATIVE major/minor

D MAJOR SCALE: D - E - F# - G - A - B - C# - D

SCALE DEGREES: 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 - 1

B MINOR SCALE: B - C# - D - E - F# - G - A - B

SCALE DEGREES: 6 - 7 - 1 - 2 - 3 - 4 - 5 - 6

*these keys are RELATIVE because they use the same key signature of 2 sharps

D Major

B Natural Minor

NATURAL MINOR SCALE

The NATURAL MINOR SCALE exists naturally based on an existing major key signature. You can find a natural minor root by counting to scale degree 6 in any major key. If we then label that note the root of the minor key, the scale degrees for natural minor are:

1 - 2 - b3 - 4 - 5 - b6 - b7 - 1. Natural minor is used in folk music, pop songs, and some Classical music.

“Bury a Friend” Billy Eilish (2019)

HARMONIC MINOR SCALE

The HARMONIC MINOR SCALE is the most used minor scale in folk, pop, and Classical genres because it has a “raised leading tone” - meaning that the seventh scale degree is not lowered like it is in the natural minor scale. The scale will still use the minor key signature, but the seventh scale degree will be “raised” from the natural minor - meaning a flat note will become a natural or a natural note will become a sharp. Because of this, the key will always have an accidental (since harmonic minor is not a true key signature). The scale degrees for harmonic minor are:

1 - 2 - b3 - 4 - 5 - b6 - 7 - 1.

On the right, you can listen to Billy Eilish’s “Bury a Friend” in G Harmonic Minor.

MELODIC MINOR SCALE

“Pluto” Björk (1997)

The MELODIC MINOR SCALE is the least used of the three modes of minor outside of Jazz. There is one form of it in Jazz and one in Classical - the Classical version ASCENDS (goes up) with one set of notes and DESCENDS (goes down) with a different set of notes.

Ascending Melodic Minor: 1 - 2 - b3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - 7 - 1

Descending Melodic Minor: 1 - b7 - b6 - 5 - 4 - 3 - 2 - 1 (this is the same as Natural Minor descending)

In Jazz, the ascending version is used for both directions.

On the right, you can listen to Björk’s “Pluto” in D Melodic Minor.

RECAP VIDEO

MEMORIZE THIS WEEK …

Order and rules of sharp and flat key signatures

Rule of accidentals in music with key signatures

The Circle of Fifths: key signature, relative major and minor scales, placement on circle (this might take you a little while, but start this week)

Scale degrees for natural, harmonic, and melodic minor scales