PRINCIPLES OF NOTATION

& RHYTHM

INTRODUCTION

This illustration is very inaccurate. Don’t get me started.

From the Caveman Era™ to approx. 1,000 years ago, humankind was cool with just performing music by rote, memory, call and response, or improvising like the Neolithic jazz cats they were. Eventually, the art form of music (as all edifices of humanity are wont to do) got too complicated for our own good and we had to start writing things down.

Guidonian Hand: Another reason to be glad you don’t live in the Medieval Era …

Now picture Europe in the Medieval Era: Moats. Plague. Monks running around chanting like they’re in some sort of Halo soundtrack recording session. One of these monks, GUIDO D’AREZZO (the most famous Guido), started composing musical works that were too long for memorization. He started using a system to keep track of the notes, and thus, the first notation of WESTERN CLASSICAL MUSIC (the music heritage, notation system, and repertoire developed over the last 1,000 years in western Europe) took shape.

The GUIDONIAN HAND was a system that used each digit of the fingers to represent different notes and was a way to teach singers more complicated music than they could memorize. Do not ask me how this worked, I’m a conductor, not a Medieval musicologist.

Eventually the digits on the hand were replaced with four horizontal lines on paper and symbols, called NEUMES, were placed on the lines vertically to represent pitch frequency (high versus low). When the four lines weren’t doing enough, a fifth line was added. Neumes were eventually replaced by NOTES and their shapes became more streamlined and formalized to represent rhythm.

Neum’usic notation, who dis?

This is where we come in …

As we get started, know that this is just ONE way of learning, reading, and studying music. This is the western European model that the United States has also adapted since our dominant culture is based off that of the European colonists who occupied America 400 years ago when European music was already formalizing. There are rich traditions of music theory in other parts of the world (India, Turkey, and China to name a few …) but this class will focus on the music theory practices that make up the majority of music academia in the United States. This model is not superior to others or the be-all end-all. It has many limitations. It also has a lot of rich, complex, and very interesting properties that we will explore this quarter (and for another 5 quarters if you stick out the entire Music Theory series).

Knowing music theory will help you to be a better musician, music consumer and patron, music composer and producer, and perhaps citizen of the world as you connect deeply with a language and art form much greater and more significant than the limitations of your experiences up to now. I invite you to keep an open mind, a fervor for knowledge, and to be patient with yourself on the occasions that you struggle.

Here we go :)

MUSICAL CONSTANTS

Musical Staff

While there are infinite possibilities for ordering and reordering the elements of music, you might be surprised at how many little puzzle pieces fit together. To begin, every time you read music, you will do so on a musical staff. The MUSICAL STAFF is the “graph” that all music is anchored to and that which allows you to read notes and rhythms accurately. With some exceptions we won’t worry about in this course, all musical staffs are comprised of five horizontal (and parallel) lines at an even spread across a page in portrait orientation. You read music on a staff from left to right (like a book) and when you reach the end of a line, you pick up again on the left of the next line down (also like a book).

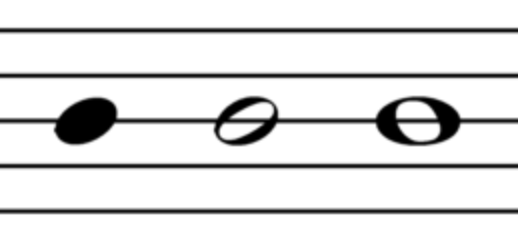

Different Note Heads

PITCH (a sustained frequency of sound vibration) is represented on the staff by the vertical placement of a note head. NOTE HEADS are small, circular (not perfectly circular, a little like a fat oval) symbols that can be fully filled in or left hollow depending on what rhythm it is representing. RHYTHM is the ordered pitch events in time and is represented by alterations made to note heads and other symbols. We can look at these two concepts on the x and y access of a graph where the x-axis represents rhythm (events over time) and the y access represents pitch (the sustained frequency of a sound vibration).

The remainder of this unit will be devoted to understanding rhythm as a foundational structure. We will add pitch and notes starting in the next unit.

RHYTHM

RHYTHM is the pattern of movement in time as defined by the Harvard Music Dictionary. This concept encapsulates the flow of hip-hop lyrics, the flurry of notes in a solo violin cadenza, the complicated layering of West African Drumming, or the precision of Indonesian Gamelan ensemble performance.

Rhythm is notated in Western Classical Music with a series of note heads on a staff and other symbols attached to the note heads. Knowing what each means, musicians interpret the symbols mathematically to perform the rhythm of a piece of music. This is done within the confines of a fixed speed called a TEMPO. If you have ever tapped your foot along to a piece of music, snapped your fingers, or danced, you have been locked into tempo. It is a very human concept (and a bird concept) and we do this as babies without much training.

The rhythmic symbols of Western Classical Music are all based on the assumption that the composer, musician, and listener has a preference for symmetry (which is not true for much of the world’s music traditions), but this makes sense in the context of monks of the Catholic Church developing this system to be used for religious music and chant. Western Classical Music’s favorite number is 4.

4 Measures on a Musical Staff

The musical staff is segmented into easily-consumable chunks called MEASURES or bars. In a piece of music, every measure takes up the same amount of space and time. What happens inside the measure is rhythmically different from other measures, but they all have the same value. It’s like how 4+4, 5+3, and 6+1+1 all equal 8. The measure is the “total” of a passage of rhythm and will take the same amount of time to complete as the measure before and the measure after. The vertical lines separating measures from each other are called BAR LINES.

Every line of music ends with a bar line as you continue reading the next measure starting with the line below. You know a piece is over when you reach a DOUBLE BAR LINE like in the eight-measure example below:

QUARTER NOTES

Since Western Classical Music’s favorite number is 4 (seriously, there are jokes about how musicians can’t count past 4 …), the assumption is that a measure will occupy the space of four BEATS (4 taps of your foot, 4 claps, 4 snaps, 4 head bangs, etc.). These beats have a symbol called QUARTER NOTES because they each retain the value of a quarter of the staff. Quarter notes look like a filled in note head with a STEM coming off of them. Stems go up off the right of the note head for lower notes in the staff and down off the left of the note head for higher notes in the staff. Each quarter note gets one beat so when you count them, they just move through numbers like: 1 2 3 4.

HALF NOTES

A HALF NOTE takes up half of a regular measure. They look like quarter notes except the note head is hollow rather than filled in. Half notes are counted with a comma (“,”) between two beats to show that the note takes up both beats like: 1 , 2 3 , 4.

WHOLE NOTES

A WHOLE NOTE takes up an entire measure. They look like just a hollow note head without a stem. Since it takes up all four beats, it is counted like this: 1 , 2 , 3 , 4. The slight misnomer about whole notes is that some pieces of music do not have four beats per measure. So in pieces with less than four beats, you can’t fit in a whole note at all. For pieces with more than four beats, you will need more than a single whole note to fill in an entire measure. Luckily, most pieces in Western Classical Music have four beats per measure.

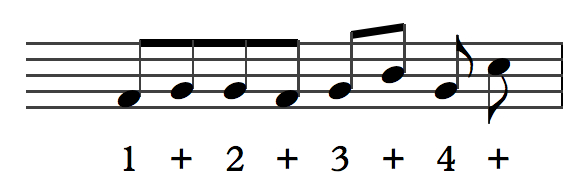

EIGHTH NOTES

EIGHTH NOTES are what you use to perform rhythms that are faster than the quarter note beat. Eighth notes generally come in pairs and the pair is equal to a quarter note. Another way of thinking about it is that each eighth note gets half a beat; there are eight per measure. Eighth notes look like quarter notes except two are attached to each other with a BEAM. You can also attach four together to make two counts worth of eighth notes. When a single eighth note is used, the beam is removed and the stem becomes a FLAG (so single quarter notes have stems and single eighth notes have flags). Flags curl down to the right if the stem is going up and up to the right if the stem is going down (see the picture). When you count eighth notes, you use the number where the eighth note lines up with the beat and an “+” (we say “and”) on the eighth note that splits the beat. To count a measure of eighth notes, you would say: “one-and-two-and-three-and-four-and”.

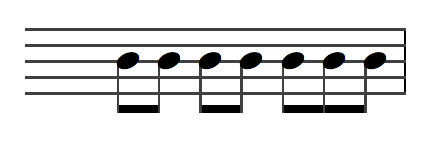

SIXTEENTH NOTES

We can further divide eighth notes in half and create SIXTEENTH NOTES. Sixteenth notes each occupy a quarter of a beat and four of them together make one beat (there are sixteen per measure). Sixteenth notes look like eighth notes but they use two beams instead of one. Any number of sixteenth notes can be attached to each other with two beams (usually in sets of 4 to occupy one beat) and a single sixteenth note has two flags instead of one. When counting sixteenth notes, a beat is divided into four segments: 1 e + a which is pronounced “one-ee-and-uh”. An entire measure of sixteenth notes would be counted “one-ee-and-uh-two-ee-and-uh-three-ee-and-uh-four-ee-and-uh”.

There are notes that are technically infinitely shorter than sixteenth notes (32nd notes, 64th notes, etc.) but we will not learn them in this class. To make shorter notes, simply add another beam or flag to halve the value of a note.

Combinations of different note values are combined to create rhythms (see below) with the value in each measure always equaling the same number (usually four). While notes are used to represent sounded pitch, there is an equally important rhythmic concept to represent silence or the space between notes: the REST.

RESTS

Rests have all the same rhythmic values that notes do but they look different so you can tell by the symbol when not to play or sing. When counting a rest, you allow the same amount of time to pass in silence as you would if you were sustaining a note. To write counts for rests, you write the same beat numbers and durations but you put them in parenthesis to show they are there but silent. The diagram below shows measures of rest divided by whole rest, half rests, quarter rests, eighth rests, and sixteenth rests.

If this looks unnecessarily busy to you - you are correct! In music, we only use the “greatest common factor” rest to fit into a space. So if we needed to rest for three beats, we wouldn’t use 6 eighth notes to show that silence, but rather, a half rest and a quarter rest (2 + 1 = 3). If you must rest for an entire measure, you will simply see a whole rest. And when you rest for multiple measures, you will see a MULTI-MEASURE REST like this one that instructs you to be silent for fifteen measures.

FYI … British Commonwealth countries (England, Canada, Australia) have different names for notes and rests like breve, semibreve, crotchet, quaver, semiquaver, etc. If you ever see a music video or diagram using these words, don’t worry about it!

Note and rest division makes a visually pleasing “rhythm tree” of subdivisions. This is a very helpful chart to recreate and memorize as you work through rhythms through this course:

METER

All of the examples above are predicated on the constant of a musical measure representing four even beats - but this won’t always be the case for every piece of music you come across. Many pieces are in different METERS - short, consistent patterns of beat and pulse over time. Meter can be broken into a variety of categories and qualifiers based on “big” beats (what you tap your foot to) and SUBDIVIDED beats (how that beat is broken down into smaller, equal parts).

Duple Meter

DUPLE (AND QUADRUPLE) METER

DUPLE is a “big beat” concept meaning that the number of beats in a measure is divisible by two and is, therefore, symmetrical. The examples above are all of four beat patterns so they are all quadruple - but quadruple meter falls into the larger category of duple since duple is more encompassing. Most dance music is in duple/quadruple meter as well as marches because having that even and symmetrical feel helps to keep things orderly and balanced on your feet.

TRIPLE METER

Triple Meter

TRIPLE is another “big beat” concept meaning that the number of beats in a measure is divisible by three and is, therefore, uneven. While duple is the most common meter, triple is the second. Triple meter has an emphasis on the first beat with less emphasis on 2 and least emphasis on 3. The most common triple meter musical type is the WALTZ, a dance form popular in 18th and 19th century Europe. Lots of music today is also in triple time but it is not very common in popular music.

SIMPLE METER

SIMPLE (and compound) refer to the SUBDIVISION of the beat or how the big beat is divided into smaller chunks. When a quarter note is divided into two equal eighth notes, this is an example of simple meter. Simple meter is the subdivided concept of duple meter. To have a song in simple duple meter, you would have an even number of beats divided into an even number of sub-beats. All of the examples above are in simple duple meter. Simple triple meter would be three big beats each divided into two subdivisions.

Simple Quadruple Meter (1 + 2 + 3 + 4 +)

Simple Triple Meter (1 + 2 + 3 +)

COMPOUND METER

COMPOUND meter is when a beat is subdivided into three even sub-beats. Swing jazz could also technically be considered compound meter although many would argue swing is a stylistic interpretation rather than a strict meter type.

Compound Duple Meter (1 + + 2 + +)

Compound Triple Meter (1 + + 2 + + 3 + +)

COMPLEX METER

COMPLEX METER is most common in modern classical, a lot of metal and progressive rock music, and many world music traditions (like that of Central and Eastern Europe). Complex meter is a catch all term for any pattern of beats that doesn’t fit into one of the categories above. Complex meter often incorporates prime or odd numbers as the big beat or the subdivision. Generally, the uneven patterns are grouped into segments of twos and threes, lending uneven emphasis to certain beats every two to three notes. Complex meter could be a piece that has 5 quarter notes per measure (1 2 3 4 5) or a piece that has 7 eighth notes per measure (1 + 2 + 3 + +).

Complex Meter (1 2 3 4 5)

Complex Meter (1 + 2 + 3 + +)

TIME SIGNATURE

TIME SIGNATURES are a set of numerical symbols at the beginning of a piece of music that serve to help the musician understand what meter the piece will be in. This provides the player with the number of beats per measure (important to know before you start performing the piece) and also how the beats will be subdivided. A time signature consists of two numbers displayed one on top of the other.

The bottom number represents what note value gets the beat (what note to tap your foot to).

The top number represents how many of them will fill each measure.

The most common time signature is 4/4 - meaning there are four quarter notes per measure. It is a simple quadruple meter. This time signature is so common, in fact, that you will often see it represented as a “C” for “Common Time” instead of 4/4. Other common time signatures and their breakdown follow:

3/4 - three quarter notes per measure; simple triple meter

2/4 - two quarter notes per measure; simple duple meter

2/2 - two half notes per measure, or “Cut Time” represented by a “C” with a vertical slash; simple duple meter. This seems like it would be the same as 4/4 but it is actually a bit different because you tap your foot on the half note and it has a different feel.

6/8 - six eighth notes per measure (usually beamed in groups of 3 so you feel the beat in compound meter as 1 2 3 4 5 6); compound duple meter

9/8 - nine eighth notes per measure (usually beamed in three groups of 3); compound triple meter

12/8 - twelve eighth notes per measure (usually beamed in four groups of 3); compound quadruple meter

5/8 - a mixed meter that is counted as 1 2 3 4 5 or 1 2 3 4 5

You can theoretically have any time signature as long as long as the denominator (number on bottom) is a 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, etc. (a number that represents an actual note value). The top number represents a cycle of beat pattern that repeats regularly so usually the top number is a fairly low value since music tends to repeat in short, consumable and predictable patterns. The highest nominator (the number on top) you will see with any regularity is probably 15. This would be used in the case of 15/8 - a complex compound meter where there are 5 groupings of 3 eighth notes per measure.4

In addition, one more concept you will run into with modern Classical music is MIXED METER: where the time signature might change every single measure, or go back and forth between two different time signatures, alternating. An example might be 4/4 and 7/8 alternating which would give you the feeling of a simple duple measure followed by a measure one eighth note less, then back again. The effect is that of momentum, energy, and the motion of the 7/8 bar almost tripping into the 4/4 bar.

TIME SIGNATURE EXAMPLES IN THE BILLBOARD TOP 10 (SEPTEMBER 2020) …

4/4 TIME: “Dynamite” - BTS

2/2 TIME: Laugh Now Cry Later - Drake ft. Lil Durk

12/8 TIME: “Before You Go” - Lewis Capaldi

MORE TIME SIGNATURES …

3/4 TIME: “Chorale from Jupiter” - The Planets Suite - Gustav Holst

6/8 TIME: “We Are The Champions” - Queen

5/4 TIME: “Take Five” - Paul Desmond

2/4 TIME: “Magnetic Rag” - Scott Joplin

7/4 TIME: “Solsbury Hill” - Peter Gabriel

MIXED METER: “The Dance of Eternity” - Dream Theater (this song changes time signatures 108 times)

COUNTING WITH TIME SIGNATURES

Let’s try a few examples where we look at short rhythmic exercises and try to figure out the counts. You can do this by clapping along, singing, or playing an instrument. This is similar to what your assignments will be this week …

The first thing you need is a METRONOME which is a device that helps you keep track of your BPM and perform rhythmics accurately. You can use an analog or digital stand-alone metronome but there are tons of free website and app metronomes like these:

Pulse App for iOS

Pro Metronome App for Android

Set the metronome to 80 BPM to start (if this all feels like review to you, you can set it to any BPM faster or slower).

Decide what the time signature is telling you - how many beats and what kind?

Look through the measure(s) and decide if it seems like mostly long beats, mostly short beats, are there combinations? Patterns? Rests?

When clapping, singing, or playing along, sustain notes for their full value. Don’t just “touch” the beginning of a long note - play or sing through it. If you are clapping, keep your hands together for the duration of the note.

Don’t be stingy with rests. Early musicians often don’t allow rests to have their full value and come in on the next note too early. Having a metronome on when you count, tap, play, or sing helps a lot!

Tap your foot along with the BPM - tapping your foot to the beat will help you accurately line up the rhythms you’re performing. DON’T tap your foot to the rhythm, only the consistent beat the metronome is generating!

With these steps in mind, try counting and performing the following examples below …

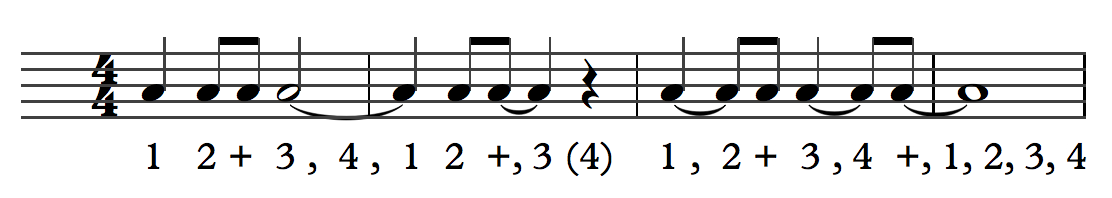

TIES & DOTS

Unfortunately (fortunately?), rhythm can be quite a bit more complicated than just using the right number of notes and rests in a given measure. Sometimes you need to sustain a note or rest for a duration that is not a perfect fraction. For this, we use ties and dots.

TIES

A TIE is a musical symbol that connects two or more rhythmic notes (on the same pitch) and serves to connect these notes into one longer note. Ties are arcing lines that move from note head to note head, hovering at the center of the note head on the opposite side of the note’s stem. You need a tie for each note you attach (you cannot use one tie over a span of several notes). Ties are most commonly used over bar lines and connecting notes to equal sustain values that are not fractionally possible. If there is a better note value to represent the length of note you want sounded, don’t use a tie. Ties are only used for notes and not for rests. To rest for longer, just add more rest symbols to the music. Here are some good and bad examples of using ties:

Don’t use a tie if you can use a simpler note value that doesn’t need the tie

Four measures of tied rhythms with counts

DOTS

A DOT is a musical symbol that adds value to a note (and on very rare circumstances, a rest). The dot can be found on the right side of the note head and it adds half the value of the original note. You can figure out dotted note values by following this equation where “x” is the duration of the original beat:

x + 1/2x = x.

The most common dotted notes and their values are shown below:

Dotted Half Note

(2 + 1 = 3)

Dotted Quarter Note

(1 + 1/2 = 1 1/2)

Dotted Eighth Note

(1/2 + 1/4 = 3/4)

Dotted Sixteenth Note

(1/4 + 1/8 = 3/8)

Dotted Whole Note

(4 + 2 = 6)

Dotted whole notes can only be used in time signatures of 6/4 or greater.

A dotted half note equals 3 quarters, a dotted quarter equals 3 eighths, a dotted eighth equals 3 sixteenths, a dotted sixteenth equals 3 thirty-seconds and so on.

Here is the same example from earlier but with dotted notes substituted where possible. Notice that we don’t dot notes over bar lines. Also notice that the eighth note to quarter note tie in measure two isn’t replaced with a dotted quarter note. This is because we don’t dot notes in the middle of a measure (it makes the measure much harder to read) but, instead, always show exactly where the measure splits in half (unless we’re in triple meter).

SOME MORE ADVANCED CONCEPTS …

SYNCOPATION

The concept of SYNCOPATION is when a regular pulse is kept on the DOWNBEAT (the numbered beats of the measure - where you tap your foot “down”) but the rhythm of the melody or supporting accompaniment accentuates the UPBEATS (the “ands” of the beats or eighth notes that split the beat in half). Oftentimes this will take the form of an eighth note on the first beat of a measure followed by a lot of quarter notes that are overlapping beats, like this:

When you split out the syncopated quarter notes into tied eighths, you can see how the counting system works:

The video below explains syncopation in more depth with lots of visual/aural examples! The YouTube channel 12tone is super, super helpful for reviewing basic music theory concepts. Hit like and subscribe!

ANACRUSIS

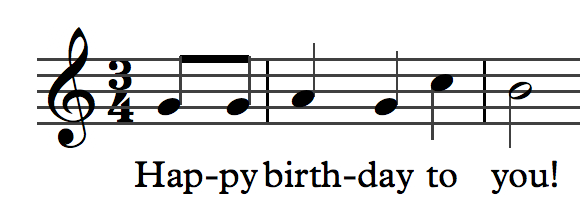

“Happy” is a two-note anacrusis in 3/4 time

The term ANACRUSIS (also referred to as a “pick-up”) is a rhythmic effect that occurs in music where the first note starts before the first measure. This “pick-up” picks the tune up before the first downbeat and is used when the first note or few notes of a piece are not the most important. An example of this is the song “Happy Birthday” where the word “happy” is a two eighth note pick-up before the first downbeat on “birth” in 3/4 time.

POLYRHYTHM

Probably my favorite part about rhythm and a concept used in many music traditions around the world is that of polyrhythm. POLYRHYTHM is when music exists simultaneously in two or more complimentary beat patterns or time signatures. This happens most often with the time signatures 3/4 and 6/8. Both have the same number of eighth notes in them but 3/4 time divides them every two and 6/8 time divides them every three. It is possible to write music where the beat switches between this simple triple and compound duple feel every measure or has simultaneous lines of music happening in each. The name for this specific polyrhythm of 3:2 is HEMIOLA. Here are some examples of hemiola polyrhythm:

Hemiola demonstration

6/8 : 3/4 POLYRHYTHM: East African Drumming from Burundi

TEMPO

As stated previously, TEMPO is the fixed speed of a piece of music (how FAST are you tapping your foot as you listen, play, or sing along?). Tempo is not the rhythm of the piece, but rather, how quickly the quarter notes go by. Tempo can be identified by a mathematical equation that results in a value of BPM (beats per minute).

Quarter Note equals 120 beats per minute (two beats per second)

To ascertain BPM, you would count the number of beats that occur in a 60-second period (one minute). This number is the BPM speed. This is the exact same way doctors determine heart-rate - but unlike heart-rate, there is no healthy speed of tempo. Like heart-rate, humans tend to prefer consistent, non-palpitating tempi (plural of tempo) … which, physiologically, correlates to the fact that we experience heart-rate. This is why music that mirrors a resting heart-rate is considered more “relaxing” while music that is much faster “energizes”. BPM is labeled at the beginning of a piece of music with the note value (most often the quarter note) equal to the numerical speed.

Table of common (but not all) Tempo Markings

One really easy way to determine tempo is to look at the second hand on a watch. Since seconds tick by at 60 per minute, we can easily find 60 BPM and 120 BPM (two beats per second). 60 BPM and 120 BPM are two of the most common tempi in Western Classical Music.

The table to the right identifies several common TEMPO MARKINGS (Italian words used to describe a range of BPM for a piece of music). Range is used as an allowance for conductor or performer interpretation - opting to perform a little slower or faster than someone else might choose. Other tempo markings may look like the one above that demarcates an exact speed for the music to be played at.

RECAP VIDEO …

MEMORIZE THIS WEEK …

Rhythm symbols (including notes and rests)

What meter is (simple vs compound, duple vs triple)

Time signatures and how to find them

How to use dots and ties

How to count and perform rhythms

How to write rhythms based on a given count pattern