SPECIES COUNTERPOINT

PART I

For whatever reason, it’s very important to music theorists that you (music theory scholars) understand the very first music theory to originate out of Western Europe. This is not the first music theory ever (Ancient Greece comes to mind and there are likely others to research in Ancient China, Ancient Egypt, etc.) but this one is deemed very “important” because it is the root of all the Western European Classical Music and Western European Classical-Influenced Pop Music we consume in the media today.

We can trace all of our (and when I say “our,” I mean the music we are studying in this course, not in the entire world) written notation and practical music application to …

… Catholic Monks of Medieval Europe.

So, let me explain.

In the Middle Ages, there were a lot of problems with European society. Most people were dirty, sickly serfs (low-skilled, feudal laborer-peasant) who either died of the Bubonic Plague or drank enough sterile alcohol to avoid the plague but then weren’t in a great state of mind to work on bettering themselves and their situations. Music in these days would have been considered a luxury most Europeans did not have access to and was broken into two categories: Sacred and Secular.

SECULAR music was the popular music of the time: ballads and folk dances performed by minstrels for the enjoyment of townsfolk and nobility. SACRED music was that of the Church (with a capital “C” because there was one, megalithic Catholic Church that answered directly to the Pope in Vatican City). Sacred music was not performed by the church congregation/attendees, but rather by the MONKS (and in some instances, nuns), who would chant prayers to the Christian God in Latin all together in unison and this is called PLAINCHANT. Monks had the time and resources to study music unlike peasants who were too busy raking muck.

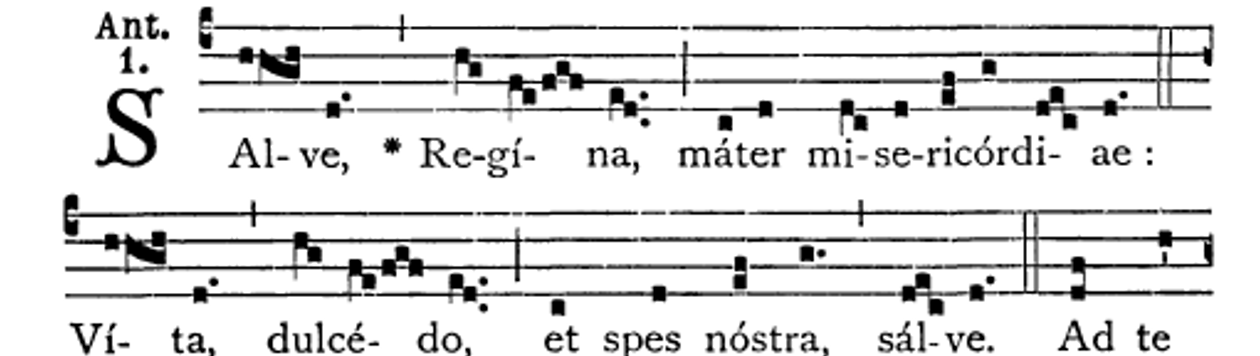

This was fine and well for a while, but eventually the monks wanted to sing more complicated chants - too complicated to commit to memory, so they had to start writing them down. Because the Church was quite wealthy in this time, monks had access to education and materials to develop the first written music notation in Europe called NEUMES.

Neumes: Almost like music but you can’t actually read them …

Using written neumes to read music worked well for longer, more complicated chants, but eventually, the monks got bored again and wanted to spice things up. They started splitting into two groups, singing the original plainchant and also the same words on a different note (so two groups in harmony) - this was called ORGANUM.

Finally, when they got bored of organum, the monks kept the plainchant and split into groups of two, three, four, or more - with each group singing different notes at different times and possibly even different words. This POLYPHONIC (multi-lined music) texture is called COUNTERPOINT and the study of it (what we’re about to do) is called SPECIES COUNTERPOINT.

Yes, all of that is confusing … let’s listen to the difference!

PLAINCHANT: all voices in unison - same notes and same words moving at the same time

ORGANUM: two groups of voices moving in non-unison intervals - different notes but same words moving at the same time and usually in the same direction

POLYPHONIC CHANT: Two or more (this is more) voice parts moving independently of each other but still harmonious and inter-connected - different notes and different words

In Music Theory, we don’t study Plainchant or Organum because someone decided those were too easy, so we just jump straight to Polyphonic Chant and start learning how to move multiple voice parts at the same time without them sounding bad together. Two voices moving in whole notes at the same time but independently of each other (independently, so not Organum) is called FIRST SPECIES COUNTERPOINT. Two voices moving where one moves at whole note speed and the other at half note speed (twice as fast) is called SECOND SPECIES COUNTERPOINT. Two voices moving where one moves at whole note speed and one moves at quarter note speed is called THIRD SPECIES COUNTERPOINT. Don’t worry about Fourth Species Counterpoint, we’re not doing that in this class.

Before you can add a second voice, though, you must start with a first voice.

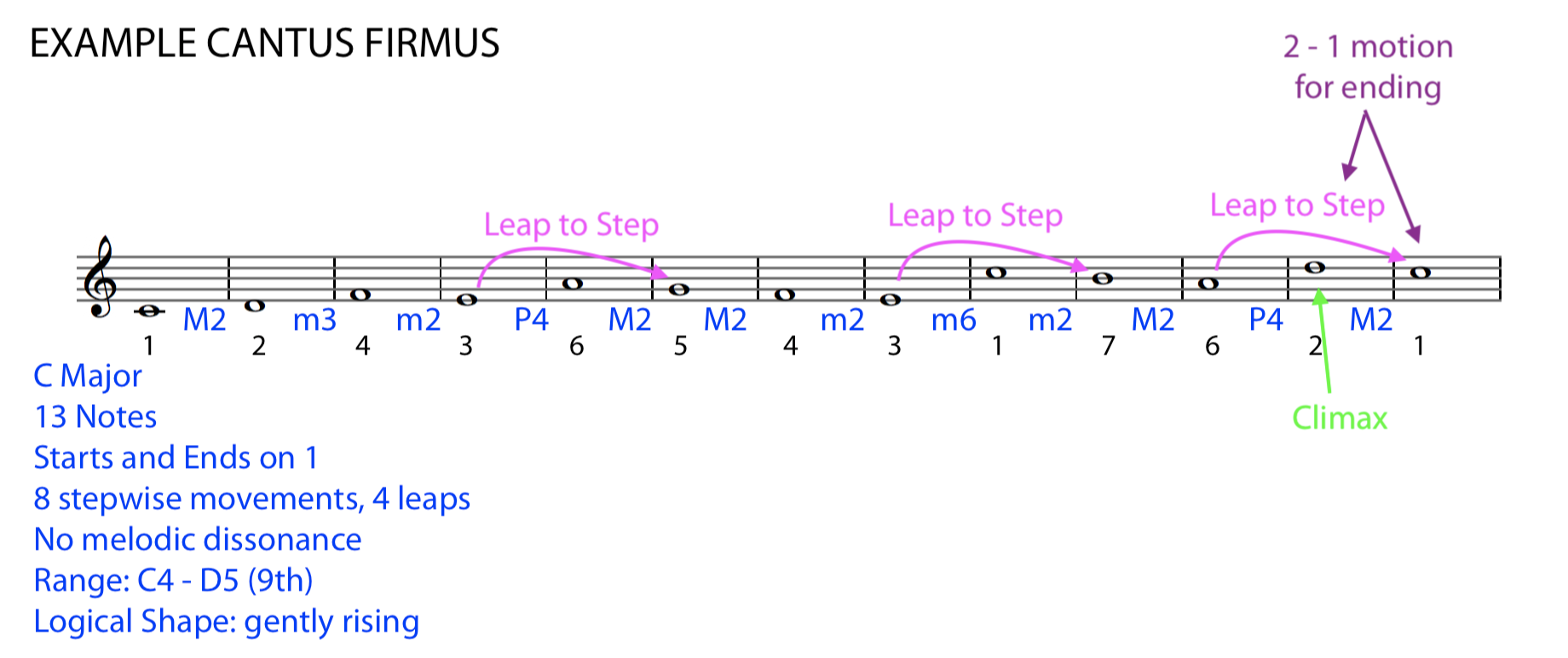

To set up a first voice that is receptive to the harmonic relationship of a second voice, it is best to follow the rules of Species Counterpoint. This first voice is called a CANTUS FIRMUS.

CANTUS FIRMUS

A CANTUS FIRMUS is a preexisting melody used as the main voice/melody for a polyphonic composition in species counterpoint practice. The term Cantus Firmus translates from Latin as “fixed melody” (Cantus = “song” and Firmus = “firm”) and the plural form is Cantus Firmi. Most Cantus Firmi are a snippet/excerpt of a Plainchant - but you can also compose your own by following the rubric below.

HOW TO COMPOSE A CANTUS FIRMUS:

Your Cantus Firmus can be in major or minor

The melody should be 8 - 16 notes long

All the notes must be whole notes (no rhythm)

Start and end on the first scale degree (tonic)

you could start on 1st, 3rd, or 5th scale degree, but definitely end on the 1st

Always change notes with each new measure (no two of the same note in a row)

The movement should be mostly stepwise with a few leaps

When choosing the next note in your melody, always move with MELODIC CONSONANCE (don’t move an augmented/diminished interval away or a major/minor 7th, which are considered dissonant)

The total range from your lowest to highest note should not exceed a tenth (an octave + two notes) and really should mostly be within an octave

Your notes can go up and down but have a logical (not random) shape - if you were to connect-the-dots with your Cantus Firmus, what shape would it create? This is called a MELODIC CONTOUR.

There should be a single CLIMAX (highest note in the melody)

No motivic repetition (meaning don’t have a pattern going throughout the entire melody)

If you leap larger than a 3rd (P4 ≤), than the next note should be stepwise in the opposite direction for balance

For instance, if you leap from a C up to an F, then the next note after F should be E

Don’t leap more than twice in a row (this scatters the melody)

No consecutive leaps in the same direction (so leap up then down, or down then up, but not up, up or down, down)

If you use the 7th scale degree, always resolve it up to the tonic/1st scale degree (“ti - do”)

In minor, only use the raised 7th scale degree once to move to the last note

If you use the raised 7th in minor and it is proceeded by the 6th, it must be a raised 6th (to avoid an interval of an augmented second/A2)

Approach the final note stepwise: 7 - 1 (“ti - do”) or 2 - 1 (“re - do”)

The following diagram shows an example Cantus Firmus (abbreviated as CF) in C Major and in treble clef. This is only an example. Cantus Firmi can be in any key, any scale mode (major, minor, etc.) and can be in bass clef, as well.

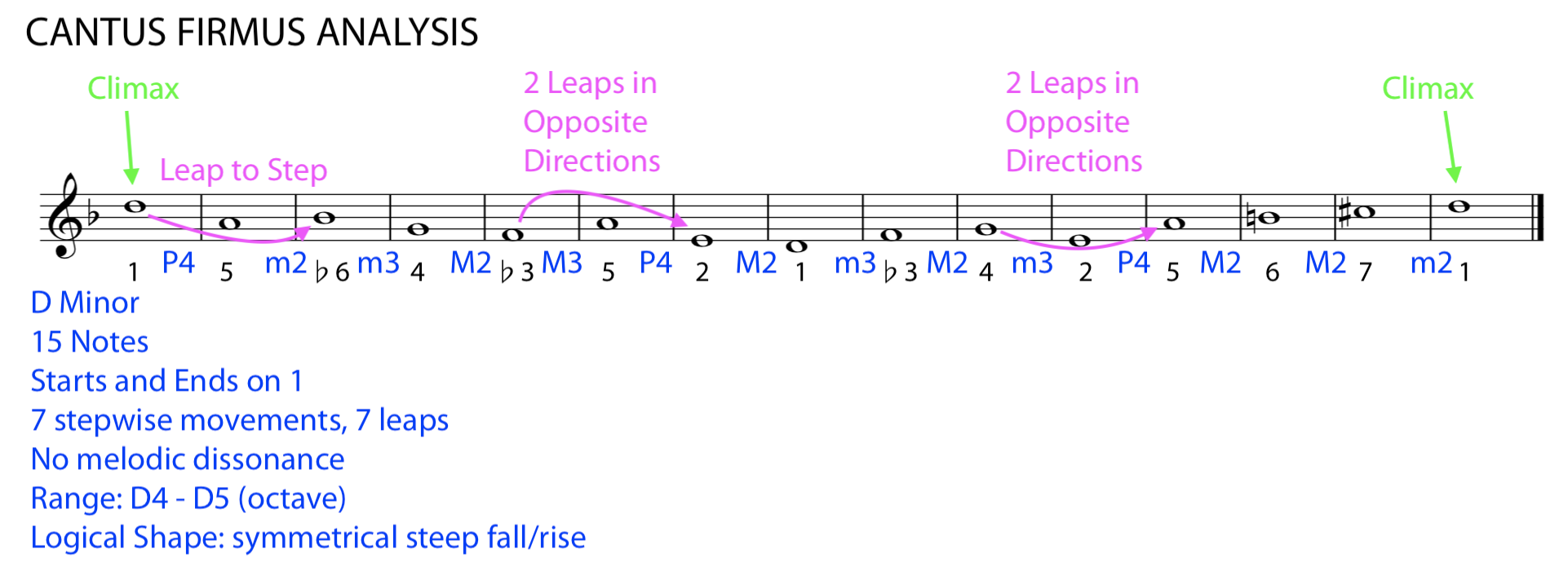

ANALYZING CANTUS FIRMI

To analyze (study, extract detail, and explain) the Cantus Firmus below, review the rules of what a Cantus Firmus should be above as well as the details included in the example above.

Ask yourself the following questions and write down the answers:

What key is the CF in? (Don’t just assume from the key signature, look at the first and last note and decide if it’s in major or minor)

How many notes are in it?

What scale degrees does it start and end on?

Check the specific intervals between each pair of notes

Where are the steps and leaps? Are there too many leaps? Too many leaps in a row? Too many leaps in the same direction?

Check for dissonant intervals (augmented intervals, diminished intervals, major or minor sevenths)

What is the range (distance between highest and lowest notes)?

What is the (hopefully logical) shape of the melodic contour?

Where is the climax?

Does the CF end with 2 - 1 or 7 - 1 motion?

When you are done, scroll down for the answers …

Notice that this example is in minor. You can tell because it starts and ends on D (so you know it’s some kind of “D _____” scale) and the key signature is one-flat (B♭) which is the key signature for D minor. You can also tell it’s in minor because the 6th and 7th scale degree are raised at the end. This is an example of melodic minor because descending lines use lowered 6th and 7th scale degrees but ascending lines use raised.

Notice, also, that there are two climaxes in this example - one at the beginning and one at the end. This is because the melodic contour of this CF is a steep fall and rise with a symmetrical shape which puts the first scale degree as the highest note at the beginning and end.

WHY ARE WE DOING THIS?

Learning how to analyze and compose a solid Cantus Firmus is the first step in approaching Western European Classical harmony practices and making good decisions about what kind of melodic and harmonic movement sounds good and bad (consonant and dissonant) as well as giving you the judgement as to when to use consonant and dissonant harmony in your compositions. You will see many, many examples of composers breaking the rules above as well as the rules we will learn for writing First Species Counterpoint. The rules are there to present a safe, subjectively “perfect” example. Breaking rules allows us to generate drama, surprise, and interest in music. In order to reject and break the rules with intentionality, it is best to first demonstrate an understanding of the rules.