THE MUSIC OF FILM

Before we begin, let’s play a game …

THE SILENT ERA (1895 - 1929)

Early Cylinder Phonograph

The first films released in the United States at the turn of the 20th century had no sound, dialogue or music. The advancement of film technology only included a moving picture without the accompanying sound of the scenes or the actors speaking. These films would often include dialogue cards interspersed through the scenes for the audience to understand what was happening through narration or quotes from the characters. This was essentially an early form of subtitling but with the titles between film shots rather than subtitled at the bottom of the shot.

To provide sound, was up to each movie theater to supply music by PHONOGRAPH or live musicians. Organists, pianists, or small ensembles of musicians were hired to play classical music or IMPROVISE to the scenes of the film. When improvising, the musician (usually one - as multiple musicians improvising on the spot could create clashing ideas) would have an idea of what mood the film scene was trying to convey and then make up music on the spot to accompany the scenes. A better improvisor would give the audience a more satisfying film experience.

Eventually, CUE SHEETS were developed to help musicians make better musical selections to accompany the films. Cue sheets were books of sheet music with public domain or copyrighted classical music arranged in categories that the publisher felt would best match scenes and moods in the movies. The cue sheets would be organized into categories like “love songs” or “death scenes” or “danger” so that the musician could easily flip to a section based on a scene and select a piece to play that would most likely match the action on screen.

Finally, PHOTOPLAY music began to be used. This is when the movie studio would decide ahead of time what precise music they wanted performed for each scene of their film. This was music specifically composed for the film (and often sounded like the classical music from earlier cue sheets).

THE GOLDEN AGE (1930 - 1950)

The “Golden Age” of Hollywood lasted from roughly 1930 - 1950 and this was the time when America was most transfixed with movies, movie studios, and the film star. A huge breakthrough in this time period was for sound to finally synchronize to film meaning that audiences could now hear sound effects, the characters speaking, and even music! The first film with synchronized sound was The Jazz Singer (1927) with Al Jolson. Films with dialogue were called “talkies” because of the added ability to hear spoken voice.

Following the advent of talking motion pictures, movie musicals became very popular. Some classics from this time period included The Wizard of Oz (1939), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), Singin’ in the Rain (1952).

At the same time, Hollywood was starting to contract with classical music composers to write original scores for their films. In 1933, Max Steiner composes the first full soundtrack score to King Kong in what would come to be known as the CLASSICAL SCORING TECHNIQUE. This was music composed and exactly timed to scenes in the movies. Usually the film would be recorded and edited first, then passed off to the composer who would compose musical themes that precisely fit the mood and timing of each scene. In addition, the use of LEITMOTIFS (“theme music” that represents characters, objects, places in the film) saw a resurgence in film music which had previously been in fashion during the second half of the 19th century in the Romantic Era of classical music (in Europe and the USA). Other classically-trained composers were signed to studios and wrote for hundreds of movies. At this time, actors, directors, and composers were all contracted with specific studios and it was very unusual for a composer to write music for a film outside the studio they were contracted with.

Enrich Korngold – The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Warner Brothers Pictures

Alfred Newman – Mark of Zorro (1940)

20th Century Fox

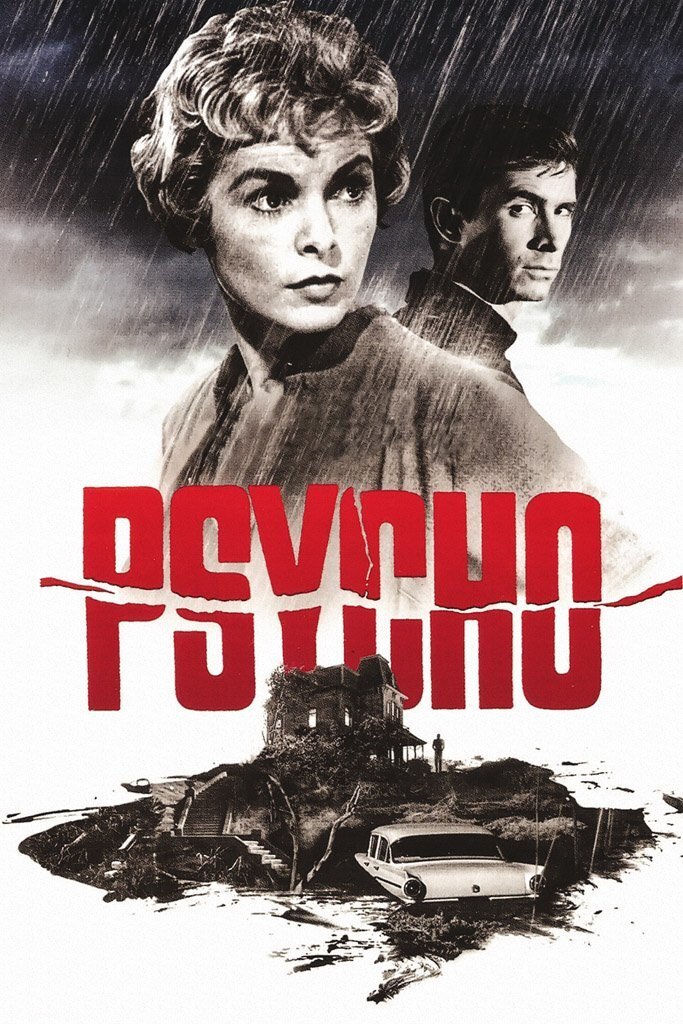

Bernard Hermann – Psycho (1960)

Alfred Hitchcock & Paramount Pictures

The Jazz Singer (1927) is the first movie to sync sound to film - and it is done with the musical scenes.

King Kong (1933) includes Max Steiner’s CLASSICAL SCORING TECHNIQUE. Notice how the music is perfectly timed to match the action in the film - a technique modern audience take for granted.

BRANCHING OUT (1950s)

In the 1950’s, composers stopped contracting with studios and went freelance. This meant that they were contracting per film with many different studios rather than just always working with a same studio or director. For the first time, non-classical and popular music began to find its way into film soundtrack - so there was less original classical-style music in a film and more radio hits or other popular-sounding tunes to fit the mood of the scenes. In some ways, this may have connected audiences to the characters better because they were connecting over a shared understanding of popular music from the time. On the other hand, without the specific original music written by composers, there was less of an immersive, special quality to films.

Film producers started the trend of hiring popular musicians to write marketable, radio-worthy songs for release in the film to help with promotion. The first time an audience member would hear the song was in the movie, but then it would be out on the radio following the film debut and remind the audience of the film. Some notable songs in this category include:

“Moon River” by Henry Mancini – Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)

“Don’t You Forget About Me” by Keith Forsey – The Breakfast Club (1985)

“Happy” by Pharrell Williams – Despicable Me 2 (2014)

A Streetcar Named Desire (1950)

Composer Alex North wrote a part-classical, part-jazz score to fit the context and mood of the film. Prior to 1950, jazz had not been featured as part of a movie soundtrack outside movie musicals or scenes where the characters were listening to jazz. A Streetcar Named Desire represents a divergence from purely classical film composing and shows the film composers’ interest in exploring other mediums outside traditional classical structures.

Elevator to the Gallows (1958)

Jazz musician Miles Davis (trumpet) composed and performed the soundtrack with only a drummer and bassist. This jazz trio in a Cool Jazz genre helped to create a dark and mysterious, yet hip tone for the movie - and solidified Cool Jazz as the soundtrack to Film Noir.

POP, JAZZ & WESTERNS (1960s)

Music for movies diversified with more niche movie genres in the 1960’s. Soundtracks of composed film scores became increasingly formulaic and themed within genre:

Westerns sounded spirited with a flare for Americana

Exotic Adventures Films used non-western scales and world instruments

Sci-Fi Films sounded eerie and unsettling

Spy Movies relied on cool jazz

Movie producers began developing soundtracks of all commercial pop music – like a themed mix tape to go with a film. The selling of film soundtracks also contributed to the movie’s success.

The Graduate (1967)

“The Sound of Silence”

“Mrs. Robinson”***

“Scarborough Fair/Canticle”

“April Come She Will”

“The Big Bright Green Pleasure Machine”

All songs by pop/folk duo Simon & Garfunkel

with INCIDENTAL MUSIC (music in the background of scenes) by Dave Grusin

“Temp Tracks” and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

TEMP TRACKS are temporary music tracks that a director will place over scenes to show the composer the mood or feeling the director wants the scene to have while the film is still in development. The temp track is designed to help with communication between director and composer and might save time by the composer writing something for the director that is closer to what they want.

However, in order to appease the directors, composers’ original music can come out sounding too similar to the temp tracks. In fact, certain composers and studios have been sued for producing music that is too similar to another composer’s work.

For the film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Director Stanley Kubrick fell in “temp love” and discarded Alex North’s entire score for 2001: A Space Odyssey in exchange for his temp track of classical music.

Even though the composer had written a complete film score of music for the film, Kubrick could not give up the classical “placeholder” works he had been listening to while developing the film and opted to keep them instead. The clip below utilizes Also Sprach Zarathustra from Richard Strauss’s 1896 classical tone poem.

SYNTH & NEO-ROMANTICISM (1970s)

Modular Synthesizer

The SYNTHESIZER (electronic keyboard with layering and sound patching) becomes popular in scoring films in the 1970’s. A synthesizer soundtrack could be written and performed by one person rather than an entire orchestra which saved on costs, time, and the composer got exactly what they wanted. Sci-fi and horror genres become more popular and they created a space for the development of the synthesizer soundtrack.

Classical Scoring from the Hollywood Golden Age saw a resurgence with composers like John Williams, Danny Elfman, Jerry Goldsmith, etc. Neo-Romantic epic movies included such franchises as Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Star Trek, and Alien. This time also saw a return of leitmotif for characters, objects, and places in film.

DARK STAR (1974)

Dark Star was a sci-fi/horror film by director John Carpenter that featured the first all-synthesizer score. In addition to directing, John Carpenter composed and performed the music (as well as wrote, directed, and produced the film).

JOHN WILLIAMS (b. 1932)

John Williams is considered the most prolific film composer of all time. He attended UCLA, Juilliard, and Eastman School of Music. His film music inspired by Romantic composers like Tchaikovsky and Wagner so many of his soundtracks have a timeless, classical quality to them. Williams has received 51 Academy Award Nominations (5 Wins) including:

The Poseidon Adventure, Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Superman, Indiana Jones, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Empire of the Sun, Home Alone, Hook, Jurassic Park, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, Harry Potter, Catch Me If You Can, Munich, War Horse, Lincoln

John Williams’ use of leitmotif in Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) by combining new and old themes from the Star Wars Universe.

SOUNDTRACKS (1980s-90s)

From the 1980’s through the 1990’s pop culture and consumerism shaped how film studios produced music. The pop song soundtrack overtook orchestral film scoring to a large extent at this time.

Something to note:

When a character in the film can hear the music, this is called DIAGETIC MUSIC (like if it is on the radio in the scene or on a record or being performed live - or the characters are singing it) vs. NON-DIAGETIC MUSIC (when only the audience can hear it in the soundtrack).

As electronic music developed, composers blended orchestral and synthesized sound during this period. Many films had pop “theme song” by a major pop artist released along with the movie:

“Ghostbusters” by Ray Parker Jr. – Ghostbusters (1984)

“Power of Love” by Huey Lewis & The News – Back to the Future (1985)

“(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life” by Mickey & Sylvia – Dirty Dancing (1987)

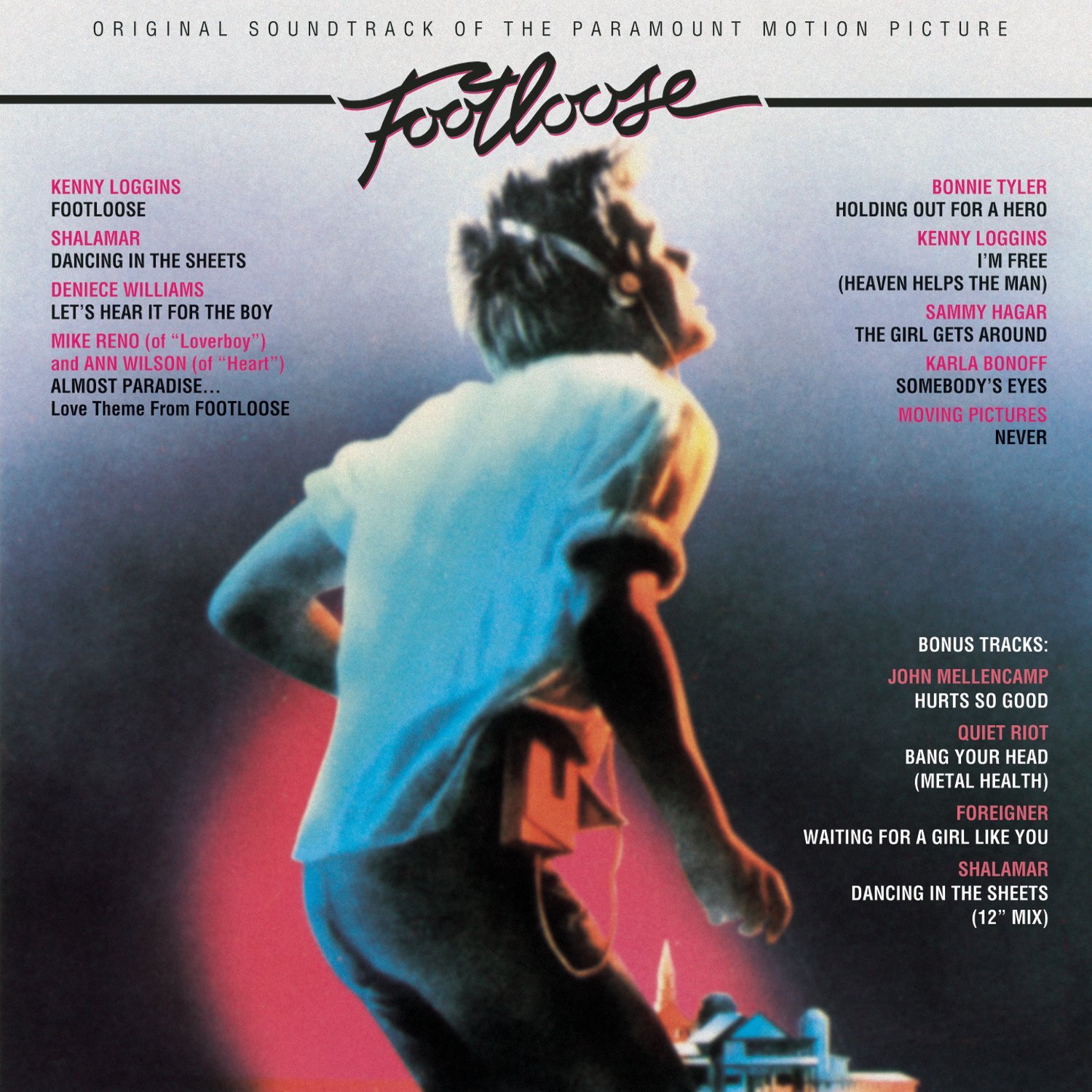

Footloose (1984)

“Footloose” – Kenny Loggins*

“Let’s Hear It for the Boy” – Deniece Williams*

“Almost Paradise” – Mike Reno & Ann Wilson*

“Holding Out for a Hero” – Bonnie Tyler

“I’m Free (Heaven Helps the Man)” – Kenny Loggins

“Somebody’s Eyes” – Karla Bonoff

“The Girl Gets Around” – Sammy Hagar

“Never” – Moving Pictures

•All songs written for the film

•Soundtrack album held No. 1 on US Billboard pop album chart for 10 weeks

•3 songs were top 10 singles

DIVERSIFICATION & BOTTLENECKING (2000-Present)

“BRAAAM”

Hollywood’s most over-used soundtrack devise since Inception (2010)

In the modern era, composers continue to stretch and redefine what constitutes as film music. Non-traditional instruments, world music, and electronic sound are incorporated. As electronic music developed, composers blended orchestral and synthesized sound. Many film soundtracks in the last decade or more have skewed more highly produced with much of the music produced electronically in music studios rather than composed and performed by live musicians.

Modern trends seek to bury the soundtrack in favor of visual effects. Due to the prevalent use of Temp Tracks, many film scores sound nearly identical and forgettable.

Inside Man (2006) starts with a monologue by Clive Owen and then launches into a Bollywood musical song, “Chaiyya Chaiyya” from the 1998 film Dil Se…

Why might the Inside Man production team made this choice?

Today, some of America’s most beloved franchises include musical soundtracks - but what role are they serving? Film and music critics suggest that over the past several decades, a shift in priority from sound/music to visual/effect has pushed the film soundtrack further to the background of film importance than ever before. Below, let’s take a look at the theme music (or lack thereof) in the Marvel superhero movie universe …