THEORY III REVIEW

CHROMATICISM: The use of at least some pitches of the chromatic scale in addition to -or- instead of those of the diatonic scale of some particular key. - The Harvard Dictionary of music

DIATONICISM: Melodies and harmonies (supporting chords) consisting of the notes in the predefined (usually SEPTATONIC - seven note) scale.

Predictable, basic, boring, safe

Everyone’s favorite 50 seconds of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9

CHROMATICISM: Replacing or filling in melodies and harmonies (supporting chords) with notes outside the predefined scale.

Surprising, intriguing, slightly chaotic, “Danger” is my middle name

If you Google “example of chromatic melody,” the very first hit is “Whip My Hair” by Willow Smith … so, here you go.

Now that we can all agree that Chromaticism is more interesting than Diatonicsm, there are a few ways to categorize the extent of Chromaticism used in a passage of music. This occurs across a spectrum from CHROMATIC NON-CHORD TONE at the least intrusive to full on MODULATION at the most intrusive. Between these two extremes, we have middle ground referred to as TONICIZATION through the use of APPLIED CHORDS (mostly secondary dominant and secondary leading-tone).

CHROMATIC NON-CHORD TONES have been showing up in examples you’ve worked on since Western Classical Music Theory I. This is when you encounter one note (often in the Soprano melody, maybe in an inner voice or Bass) that is outside the key and then it immediately resolves to a diatonic tone. This is generally a very short moment of tension and release.

TONICIZATION is the act of giving that chromatic non-chord tone a whole dang chord in its moment completely outside the home diatonic key. In general, tonicization lasts just as long as a chromatic non-chord tone but its more extreme because instead of just one note/voice outside the diatonic key, all four voices are creating a chord that doesn’t fit into the diatonic. This is a more extreme example of chromaticism because more voices are involved, but it’s still just a short event. When an entire chord is sounded out of the home tonality, that chord is referred to as an APPLIED CHORD or SECONDARY DOMINANT CHORD. This chord is almost always written in “terms” (aka “in the tonality of”) the chord it precedes; so while it seems to come out of nowhere (“Wow, such drama!”), it resolves comfortably into the following chord (“Ah, I see now - foreshadowing all along …”).

MODULATION is the term used to identify when a piece of music moves from one tonal center to another. This is the most extreme version of chromaticism (some would argue that its not even chromaticism at all) because the original tonality is completely abandoned in favor of a shift into a new key and tonality. Often, between cadence points in the original key and the new key, there are many chromatic markers that help with the transition. Modulation is all about the time spent in the new key - while the piece may eventually return to the original key later, moving to a new tonal center for at least a phrase, if not more, is good proof of modulation.

APPLIED DOMINANT CHORDS

Dominant = V chord, right?

Right. Good. Well, maybe a V⁷ chord, too. That would also count.

When we use the phrase APPLIED DOMINANT CHORD, we are referring to the use of a chord that is the V or V⁷ OF a diatonic chord in the key. We represent these chords with the V or V⁷ we are going to use over the diatonic chord it is the dominant of with a slash “/”. The following are all hypothetical applied dominant chords. The emboldened chords are the ones you typically see in use:

These are pronounced “five of two” or “five-seven of two” and so on …

There is no V/I because, well, that’s just a plain V chord, after all.

Notice that the V/iii and V/viiᵒ aren’t very popular. This is because iii isn’t an oft-used chord to begin with and viiᵒ is unstable enough as it is without adding more drama with a V/viiᵒ. “Five of diminished-seven” would be #4 - #6 - #1, a very strange chord, indeed!

V/ii or V⁷/ii

V/iii or V⁷/iii

V/IV or V⁷/IV

V/V or V⁷/V

V/vi or V⁷/vi

V/viiᵒ or V⁷/viiᵒ

To find the applied dominant chord, simply treat whichever diatonic chord you’re tonicizing as a root/tonic chord and find its V or V⁷. Notice that the dominant chord will always be major (or dominant if utilizing the 7th scale degree) because of the properties of the harmonic minor scale. So even if you’re trying to find the applied dominant chord of minor ii, it will still be major V/ii because the third scale degree of the V chord will be the raised 7th scale degree in harmonic minor!

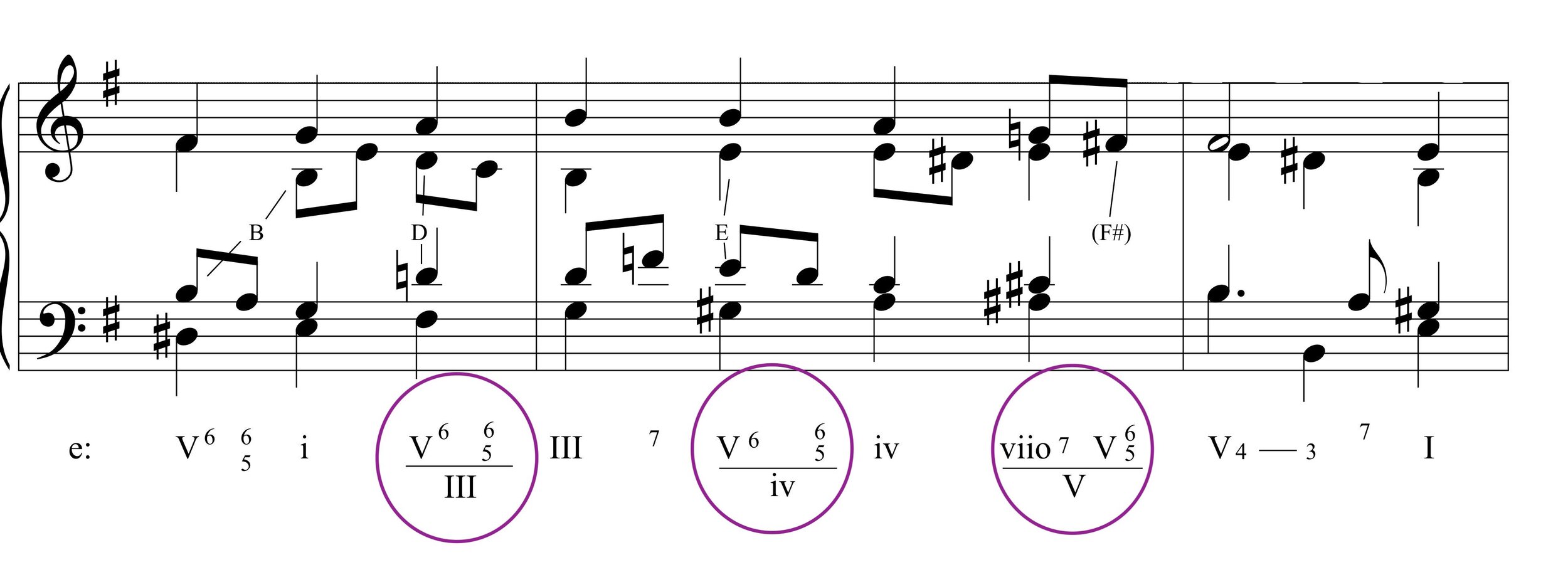

Applied dominant chords always immediately resolve to the diatonic chord in a “five” to “one” motion V - I, lending additional drama and more regular tension and release to the overall piece of music. Take a listen to these two examples; Example A has only diatonic chords while Example B has three applied dominant chords embedded into the larger progression.

The Complete Musician (Laitz) p. 437

Notice that the movement from Tonic - Predominant - Dominant - Tonic is anticipated in Example B with the use of applied dominant chords. Once the V/whatever is uses, that chord signals the arrival of the next tonal area within the larger movement of the phrase. This anticipatory nature also serves to increase the drama, suspense, and pattern of tension and release throughout the phrase in Example B that is lacking in Example A.

IDENTIFYING APPLIED DOMINANT CHORDS …

Finding the “five of ______” is actually quite easy.

Select one of your appendages with five digits (maybe it is your left hand or right hand)

Mark the DIATONIC chord with your THUMB

Count to the APPLIED DOMINANT (V or V⁷) up to your PINKY

Spell the MAJOR TRIAD or DOMINANT SEVENTH CHORD with that root

This applied dominant will usually be followed by the diatonic chord it is the “five of”

So in C Major, if we wanted to find the V⁷/ii …

Prepare my right hand …

My thumb is “D” for the “ii” chord

D - E - F - G - A lands on my pinky

A - C# - E - G for a DOMINANT SEVENTH CHORD starting on A

Therefore the V⁷/ii is A - C# - E - G and it will immediately be followed by the ii which is D - F - A

Relish sweet victory over applied chords

INVERTED APPLIED CHORDS

Not all applied chords will show up in root position. Applied chords behave just like diatonic chords in that we may choose to use an inversion of a chord in order to allow the bass line to be more melodic or stepwise in movement and not jump around as much as all root position chords would force. When encountering an inverted applied chord, it will be tonicizing and/or expanding the diatonic chord it is applied to. Therefore, V⁷/ii, V⁶⁵/ii, V⁴³/ii, and V⁴²/ii all expand the ii area (which is generally used as a Predominant).

WHEN TO USE APPLIED CHORDS

Applied chords = tasty seasoning

Applied chords are like MSG, delicious on literally everything. Use them to dress up any important moment or occasion in your chord progressions. However, there are definitely moments when they really come in handy. One of these types of moments is TONICIZING HALF CADENCES.

That’s right: ending on a V chord at the end of your phrase? What better way to prepare your palette for leaning into the V than to set it up with a V/V?

The video below shows a few examples of V/V chords in popular music including Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody,” Muse’s “Stockholm Syndrome,” “Don’t Know Why” by Norah Jones, and “I Dreamed a Dream” from Les Miserables. The video will ask you to pause and analyze the chord sequences given for the three pieces - grab a piece of paper and practice this skill along with the video!

HOW TO USE APPLIED DOMINANT CHORDS

Many of the same rules for part-writing concerning the V chord apply:

If you double, don’t double the 3rd (7 of the key) or the 7th (7 of the chord)

Resolve 3rd (7 of the key) upward if it is in an outside voice

Always resolve 7th (#4 of the key) downward (to 4)

APPLIED LEADING-TONE CHORDS

This is pretty much all the same information from above except applied to leading-tone chords which, as you should remember, refer to the vii chords. So applied leading-tone chords are vii/x chords like …

viiᵒ/ii or viiØ⁷/ii

viiᵒ/iii or viiØ⁷/iii

viiᵒ/IV or viiØ⁷/IV

viiᵒ/V or viiØ⁷/V

viiᵒ/vi or viiØ⁷/vi

viiᵒ/viiᵒ or viiØ⁷/viiᵒ

When encountering a single applied chord, they will pretty much always be a V/x or a viiᵒ/x that immediately resolve to x. We will encounter examples later of several applied chords in a row as well as transitioning fully into a new key through MODULATION. Consider how we would move from a I chord to these various applied leading tones chords …

I - viiᵒ/ii - ii = Cᴹ - C#ᵒ - Dᵐ (wow, look how chromatic!)

I - viiᵒ/iii - iii = Cᴹ - D#ᵒ - Eᵐ (gross)

I - viiᵒ/IV - IV = Cᴹ - Eᵒ - Fᴹ (ok, this one is pretty nice)

I - viiᵒ/V - V = Cᴹ - F#ᵒ - Gᴹ (crunchy, delicious tritone resolution - we have slain the Devil)

I - viiᵒ/vi - vi = Cᴹ - G#ᵒ - Aᵐ (a bit illogical - but maybe V - viiᵒ/vi - vi would give us that chromaticism we crave)

I - viiᵒ/viiᵒ - viiᵒ = Cᴹ - A#ᵒ - Bᵒ (a lot of diminished going on here - this resolution isn’t super satisfying)

Now let’s take a look at the first 8-bar phrase of FLORENCE PRICE’s “Ticklin’ Toes,” a pop piano solo from 1933. Notice the two instances of applied chords: V⁶⁵/V in m. 3 and viiᵒ⁴²/V in m. 4. They are both chords that act as a transition from a I to a V chord. Notice, also, how the inversions allow the bass to move chromatically from G - F# - F and E - Eb - D. As you listen to the video performance below, decide which applied/secondary chord is more “intense” or energizing toward the V.

Florence Price, style icon.

FLORENCE B. PRICE (1887 - 1953) was an American composer, teacher, and pianist. Her symphonic repertoire is the first by a Black composer to have been played by a major symphony orchestra.

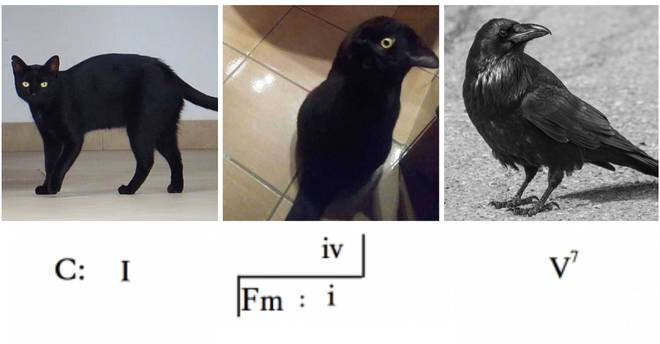

TONICIZATION

When you encounter multiple applied chords in a row for the same diatonic base chord, something that would analyze as ii/V - IV/V - V/V - V looks much messier on paper than it needs to. For these moments, the best alternative is to “tonicize” the area of the phrase into terms of the base diatonic chord. The word TONICIZATION (tawn-i-siz-ay-shun) means to treat some chord other than the tonic I or i chord as the tonic of an area for a few chords or measures but not fully modulating into that space. To do this, analyze all the chords as if they were in the base diatonic chord’s key and then bracket the group of applied chords with the base diatonic chord below like this:

A moment of tonicization occurs in Paul McCartney’s “Yesterday” as performed by The Beatles. While the piece is based in F Major, the content is of a sad nature, not fit for a major tonality. McCartney utilizes the major tonality to reminisce or express hope for the future but then shifts into minor tonicization when contemplating his sad present reality. It is expressed in the music with the brief transition to chords tonicizing the relative minor of D MINOR (the vi chord) which can be seen in the movement at mm. 3-6: I - ii⁷/vi - V⁷/vi - vi - IVᴹ⁷. If you will recall back to our chord progression work in Music Theory II, this is a “two-five-one” progression in the relative minor for just two measures before returning to the major. It’s freaking brilliant.

Also note that while The Complete Musician text teaches to put a bracket under all the tonicizing material and write the diatonic chord it’s tonicizing once underneath (as in the analysis below), it is probably more common to just write it in the more sloppy style above where you write out each applied chord.

MODULATION

The Complete Musician makes this note about tonicization vs. modulation on p. 467:

TONICIZIATION: Tonicizations usually occur within phrases. They do not disrupt the feeling of the home key; they do not have strong cadences in new keys, and they are fleeting.

MODULATION: Modulations include a strong cadence in the new key, and the new key continues after the cadence. They give the feeling that a new key has usurped the home key (at least for the moment).

A tonicized key is like visiting another country for a short trip or vacation. A modulated key is like actually moving to the other country. Maybe you eventually move back to your home country one day, but for the time being, your refrigerator and your dog and all your underwear are located in this new country.

Composers use modulation to change the mood and tone of a piece and to add drama. Have you ever met someone who actually lived in another country for part of their life? Don’t they just seem so fascinating and interesting? You’re like: “Wow, tell me more!”

There are several types of modulations, some more advanced than others. We will begin with the most basic which is MODULATION TO CLOSELY RELATED KEYS. A closely related key is a tonal center that is very similar to the original key. For the most part, keys like to modulate to the key based on its scale degree 3, 5, or 6 and here is why:

MAJOR

I - V modulation to the dominant (add one sharp or take away one flat from original key)

I - vi modulation to the submediant (this is the parallel minor)

I - iii modulation to the mediant (this is the parallel minor of the dominant and a combination of the two modulations above)

MINOR

i - v modulation to the minor dominant (add one sharp or take away one flat from original key)

i - III modulation to the mediant (this is the parallel major)

i - VI modulation to the submediant (this is the parallel major of the dominant and a combination of the two modulations above)

HOW TO MODULATE …

When modulating between two keys, the keys will overlap in a single chord or short area called a PIVOT CHORD or pivot area. This is a chord that exists in both keys without any accidentals (if you’re trying to modulate to a key where there are no pivot chords in common, the two keys aren’t closely related and you would use another method).

Let’s take a look at A Major and its dominant, E Major:

All of the chords that are circled are candidates to be pivot chords if you wanted to modulate from A Major to E Major in a piece of music. This is because the circled chords exist in both key signatures. The only chords that don’t work as pivot chords are the ones with the note(s) that is/are different between the two keys. The difference between the key of A and the key of E is the D/D# - so any chord that has a D in A Major and a D# in E Major won’t work as a pivot. The possible pivot chords for modulating from a I to a V are:

I becomes IV

iii becomes vi

V becomes I

vi becomes ii

The most common is V to I with the others in more limited appearances.

To find where the pivot chord happens, follow along in your music until you notice the modulation - you will either start seeing new consistent accidental(s) through a substantial portion of the music (including whole phrase(s) and cadence(s)) or you will see an actual “key change” where the key signature is updated to reflect the new key. Decide what new key the piece modulates to based on the accidentals, important notes in the melodic rhythm, and what chords are involved in the cadence. Once you know that key, figure out what chords are common between the new key and the old key (these are all possible pivot chords). Look backwards from the first use of the new accidental(s) until you identify a pivot chord - usually one to three chords before the first use of the new accidental. If it’s only one chord, it’s a pivot chord - if there are several pivot chords in a row, we could call it a pivot area. Note that second inversion 6/4 chords are too weak to pivot - these might be found in a pivot area but won’t count as a single pivot point.

To pivot from one chord to the next, you use a weird little bracket that doesn’t have a name and looks like this:

In the space above the horizontal line, you analyze the chord in terms of the old key. In the space below the horizontal line, you analyze the chord in terms of the new key. To the left of the bottom vertical line, you write the new key. From here, you would continue to analyze all the chords to the right of the symbol in terms of the new key until the piece is over or you modulate again. The book uses a box around the two analyses of the pivot chord rather than the bracket I’m showing here. The bracket is the way I learned and makes more sense to me, but you’re welcome to use the book way, too.

Certain diatonic chords sound better when pivoting depending on the relationship of the keys you are pivoting from and to. In general, it’s a good rule to pivot from a slightly weaker chord position in the original key to a stronger chord position in the new key. So in the example above, iii-vi is great because iii is so weak. vi to ii is good because they are relatively even chords energy-wise. I to IV is not a great choice because your ear will already feel so “home” in the original key on I - but this is a good way to trick your listener: “Haha! I brought you into the new key with a blindfold on!” V-I is trick because if you’re already on I in the new key, there isn’t much energy for you to move and show that you are in the new key. Even as I say this, you will find examples of all of the above all over music - but there is a point to be made about selecting a specific pivot with intention. The Diatonic Common Chord example from C Major to E Minor has the pivot chord of iii to i which moves from a very weak position in the original key to a very strong position in the new key.

SAMUEL COLERIDGE TAYLOR’s Violin Sonata in D Minor (1898) shows a pivot chord modulation from D MINOR to F MAJOR (which are relative major-minor keys with the same key signature) where the i in the original D Minor serves as the vi in the new F Major. This is a very typical transition in relative keys that do not need to add accidentals. I begin the analysis on p. 2 and move through the 18 measures before the pivot chord at m. 53 (i-vi) and then finish the line in F Major.

Now THAT is a three-piece suit!

SAMUEL COLERIDGE TAYLOR (1875 - 1912) was an English composer, conductor, and music professor. His most popular work is Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast and he was a very popular personality on the three occasions that he toured to the United States. He died of pneumonia at the age of 37.

SEQUENCING IN MODULATION

Dead German composers love using sequence as a way to modulate. In general, sequencing can work for both a common chord modulation (where the pivot key exists in both the previous and the new key) or a sequence can go so far away from the original key that there is no relationship between it and the new key outside the sequence. Let’s look at some examples:

TONAL SEQUENCE

Cm - Fm - Bb - Eb - Ab - D - Gm - Cm

In this sequence above, the chords are moving through C minor down by fifths (or up by fourths) this is an example of a TONAL SEQUENCE because all of the chords’ qualities match their quality in the key of C minor. If we moved through this sequence, we could stop on any chord and make that chord the new tonality moving forward. The distance from the first chord in the sequence to the new key would all count as the Pivot Area. So for the five-chord portion of the sequence below, the pivot area is five chords long:

C Minor Cm - Fm - Bb - Eb - Ab Ab Major

REAL SEQUENCE

Cm - Fm - Bb - Eb - Abm - Dbm - Gb - B - Em - Am - D - G - Cm

This sequence is a REAL SEQUENCE because the distance between the first two chords remains through the sequence. I also kept the pattern of two minor chords then two major chords throughout - which couldn’t happen in a tonal sequence because tonal sequences must keep the quality of the key. If I moved five positions in this sequence, I would get this:

C Minor Cm - Fm - Bb - Eb - Abm Ab Minor

C Minor and Ab Minor aren’t really related (there are four more flats in Ab Minor than C Minor) so real sequences are a better way of moving between unrelated keys than tonal sequences. When you have a sequence like this and the middle gets challenging to attribute to the previous or new key, the best thing to do is just call this the PIVOT AREA. This video recaps melodic sequences and harmonic sequences (where you make sequences using chords).