TRIADS &

TONIC/DOMINANT AREAS

INTRODUCTION

Now that we have tackled scales and scale degrees, we have a grasp at how a note interacts with the next consecutive note over time. We also know how notes interact in a set of two vertically or horizontally through aural and visual identification of specific intervals. When we dig deeper into harmony, the next step would be to add a third note to the mix which will interact with two that we already have in an interval. Once you add a third note to an interval, you have created a chord. Almost all Western Classical Music harmony is based on chords.

WHAT IS A CHORD?

A CHORD is three notes or more sounded harmonically all at once (BLOCK CHORD) or spread out consecutively (ARPEGGIO). Anything less than three notes would be only an interval - the third note is what makes it a chord. Many chords are four notes or more - especially in jazz harmony (which we will not study at length in Music Theory I). The most basic chord is called the TRIAD a 3-note chord where each note is the interval of a 3rd above the previous note. Because thirds occur in major and minor qualities, a combination of major and minor thirds stacked on top of one another create four distinct triad qualities as explained below …

TRIADS

MAJOR TRIAD

The MAJOR TRIAD is a triad stacked starting on the root of the major scale. Since the chord is stacked by thirds, it ends up sounding the scale degrees of 1 - 3 - 5. Major triads can also be built off the 4th and 5th scale degrees. To identify a major triad, write the root letter with a superscript capital M next to it: Bbᴹ.

Bbᴹ - Bb Major Triad, bass clef

Scale degrees: 1 - 3 - 5 (or 4 - 6 - 1 or 5 - 7 - 2)

Intervals: M3 - m3 (with a P5 between root and 5th)

Example: Bb - D - F

Sounds “happy”

Symbol: Root letter and superscript “M”

MINOR TRIAD

The MINOR TRIAD is slightly altered from a major triad in that the third scale degree (the middle note) is lowered by one half step from its major third position. This alteration it ends up sounding the scale degrees of 1 - b3 - 5. Minor triads occur on the root of minor scales. In major, the minor triad naturally occurs starting on the 2nd, 3rd, and 6th scale degrees. To identify a minor triad, write the root letter with a superscript lower-case m next to it: Bbᵐ.

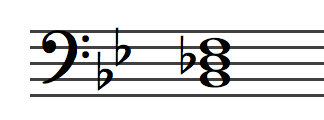

Bbᵐ - Bb Minor Triad, bass clef

Scale degrees: 1 - b3 - 5 (or 2 - 4 - 6 or 3 - 5 - 7 or 6 - 1 - 3)

Intervals: m3 - M3 (with a P5 between the root and 5th)

Example: Bb - Db - F

Sounds “sad” or “mysterious”

Symbol: Root letter and superscript “m”

DIMINISHED TRIAD

The DIMINISHED TRIAD goes one step beyond a minor triad in that the fifth scale degree (the top note) is lowered by one half step from its perfect fifth position. This alteration it ends up sounding the scale degrees of 1 - b3 - b5. Diminished triads occur on the seventh of scale degree of a major scale. To identify a diminished triad, write the root letter with a superscript degree symbol next to it: Bb°.

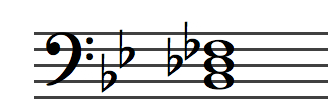

Bb° - Bb Diminished Triad, bass clef

Scale degrees: 1 - b3 - b5 (or 7 - 2 - 4)

Intervals: m3 - m3 (with a d5 between the root and b5th)

Example: Bb - Db - Fb

Sounds “dangerous” or “dissonant”

Symbol: Root letter and superscript “o” (degree symbol)

AUGMENTED TRIAD

The AUGMENTED TRIAD fills in the final position of two stacked major triads. This alteration ends up sounding the scale degrees of 1 - 3 - #5. The symbol for augmented is a superscript plus sign next to the root since the chord is wider than a major chord: Bb⁺. Augmented occurs in only one specific location: the III⁺ in a melodic minor scale.

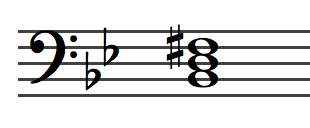

Bb⁺ - Bb Augmented Triad, bass clef

Scale degrees: 1 - 3 - #5 (or b3 - 5 - 7 in harmonic minor)

Intervals: M3 - M3 (with an A5 between the root and #5th)

Example: Bb - D - F#

Sounds “dreamlike” or “uneasy”

Symbol: Root letter and superscript “+” (plus sign)

MORE ACCIDENTALS

If you play around with altering the third and fifth of triads to get different chord qualities, you will notice some problems, especially when you alter the fifth for diminished and augmented chords.

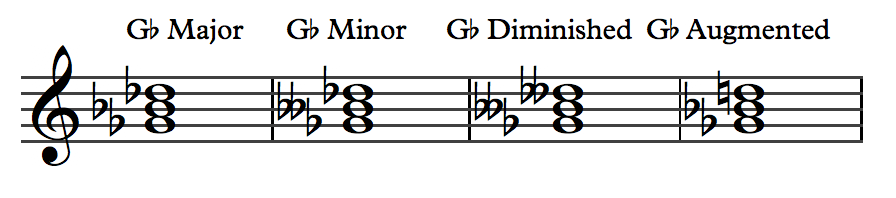

Let’s look at the Gb triad …

Gb Major Triad: Gb - Bb - Db

Gb Minor Triad: Gb - B?? - Db (lower the Bb again)

Gb Diminished Triad: Gb - B?? - D?? (lower the Bb and the Db)

Gb Augmented Triad: Gb - Bb - D

How do we lower a third or a fifth that’s already flat? We have to double flat it! A DOUBLE FLAT is literally two flat signs next to each other before a note head: “bb”. A double flat lowers the pitch by two half steps (a whole step) so a “white key” on the piano with a double flat next to it would really be played as one white key to the left. Enharmonically, double flat notes are really …

Cbb = Bb

Dbb = C

Ebb = D

Fbb = Eb

Gbb = F

Abb = G

Bbb = A

So when writing out the chord tones for Gb triads, they are:

Gb Major Triad: Gb - Bb - Db

Gb Minor Triad: Gb - Bbb - Db

Gb Diminished Triad: Gb - Bbb - Dbb

Gb Augmented Triad: Gb - Bb - D

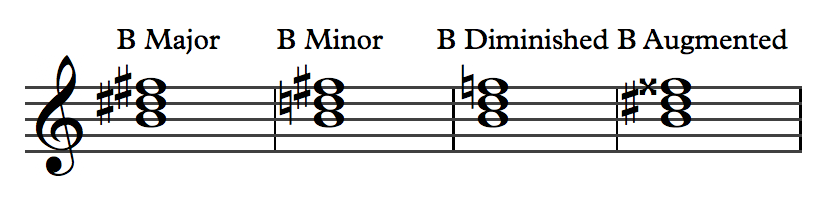

Let’s also look at the B triad …

B Major Triad: B - D# - F#

B Minor Triad: B - D - F#

B Diminished Triad: B - D - F

B Augmented Triad: B - D# - F?? (raise the F# again)

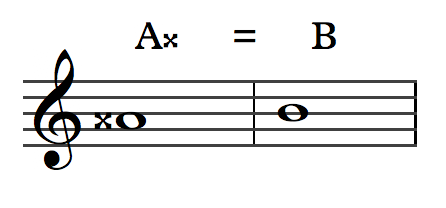

The dilemma occurs when we try to raise a fifth that’s already a sharp. We have to double sharp the note. A DOUBLE SHARP looks like an “X” (with little weird squares on the tips) in the accidental position and it raises a note two half steps from the natural version. So enharmonically …

CX = D

DX = E

EX = F#

FX = G

GX = A

AX = B

BX = C#

The chord tones for B triads are therefore:

B Major Triad: B - D# - F#

B Minor Triad: B - D - F#

B Diminished Triad: B - D - F

B Augmented Triad: B - D# - FX

TONAL AREAS

WHAT IS TONALITY?

Tonality is a mostly Western Classical Music Theory concept that divides different sections of a piece of music as existing in temporary, unmarked key signatures. These sections create contrast, pacing, tension and release for the listener and help to convey mood and storyline within a larger piece of music. To define these sections, the majority of pieces are divided into three parts (and each part into smaller sub-sections): Tonic, Predominant, and Dominant. We will talk about the two most important, Tonic and Dominant, in this course.

The most basic two tonal centers to begin recognizing first are the TONIC and DOMINANT areas as defined below. If we liken a piece of music to a story being told, Tonic is like the main character’s “home” and Dominant is like a destination the character journeys to (maybe they are on a quest, maybe they have never left the Shire before). The story begins at home (Tonic), then the character goes on a journey (we would call this movement Predominant) and gets to a destination (Dominant). Because I’m a big ol’ nerd, (and your Millennial-aged professor), I will demonstrate these areas using GIFs from the best film series of the early aughts: The Lord of the Rings.

TONIC AREA

As mentioned previously, another name for the root or first scale degree is the “tonic”. The word “tonic” can represent both the root of a scale or the area of the music (rhythmically) that is performed over the major chord built off the first scale degree. This TONIC CHORD is the major chord consisting of 1 - 3 - 5 and is referred to in music as the I CHORD (“I” being the Roman Numeral for “one”). The tonic area represents home base and can most often be found at beginnings and endings of musical works. It has a settled, anchored feeling to it because its root is the root of the entire scale.

DOMINANT AREA (or, There and Back Again: A Hobbit’s Tale)

The word “dominant” is used in music to label both chords and areas. We will not study dominant seventh chords this quarter, but we will look at the area. The DOMINANT AREA is the section of the music that is built off the major chord consisting of 5 - 7 - 2 and is referred to in music as the V CHORD (“V” being the Roman Numeral for “five”). The V chord and dominant area have a lot of tension because the 7 and 2 are have a pull to the root and want to resolve. In a story, this is could be considered the moment when the character is farthest along and feels the strongest urge to return home. Often in stories, the character’s journey home is much faster than their journey away from home - and this is often reflected in music with the movement of Dominant - Tonic areas or V - I chords. To answer Frodo’s question: yes. Dominant always returns home to Tonic.

HOW TO FIND TONIC AND DOMINANT AREAS …

Know what key you are in (always double check if you are in major or minor, don’t always assume a piece is in major!)

Find the Tonic: this is very easy, the tonic is the Major I chord in major or the minor i chord in minor.

Find the Dominant: count up to the fifth of the key. With very few exceptions, the dominant is always the Major V chord.

THEREFORE …

C MAJOR

I: Cᴹ and V: Gᴹ

C MINOR

i: Cᵐ and V: Gᴹ

G MAJOR

I: Gᴹ and V: Dᴹ

F MAJOR

I: Fᴹ and V: Cᴹ

D MAJOR

I: Dᴹ and V: Aᴹ

Bb MAJOR

I: Bbᴹ and V: Fᴹ

IN CONTEXT …

Francis Johnson and his bonkers French horn

Let’s look at Francis Johnson’s Victoria Gallop (1839) for wind band as condensed into a piano transcription.

FRANCIS JOHNSON (1792 - 1844) was a free Black man born in Philadelphia and is considered to be the first African American composer of Western Classical Music as well as the first conductor of an American music ensemble that toured outside the United States.

Victoria Gallop - Francis Johnson (1839)

We can tell the piece is in F MAJOR because of the key signature and the first chord in the bass is an F Major Triad. If you are confused how, it is because this chord is broken up over two eighth notes in a technique known as STRIDE BASS (where the root of the chord is played first followed by the rest of the notes on the second eighth notes). It is halfway between a block chord and an arpeggio. So when we take the composite of F-F-A-C, we see that it’s in F Major. In F Major, the Fᴹ chord is the Tonic/I chord and the Cᴹ is the Dominant/V.

The treble clef has the melody which will have lots of non-chord tones so it’s not very helpful in figuring out the tonal area. We will just look at the bass clef.

In the third measure, we switch from Fs, As, and Cs in the bass to Es, Gs, Bbs, and Cs. When we move the C down an octave, the chord C-E-G emerges (which is the V chord!). If you’re wondering what to do with that pesky Bb, you could add it on top: C-E-G-Bb and get a V⁷ (a “dominant five seven chord” - but you will learn about that in Music Theory II). For now, just know that that is a dominant area. Take a look at the tonic and dominant areas of Victoria Galop as you play the sound on the video. How many measures long are each section? What patterns do you see that emerge?

MEMORIZE THIS WEEK …

The four triad qualities

The I - V (Tonic - Dominant) relationship between chords in all 12 keys

How to determine if an area is Tonic or Dominant