VOICE LEADING

& FIGURED BASS

By the time you have reached this point, your mind has likely been burnt out on Species Counterpoint. This next concept, Figured Bass, arose several hundred years later in the Baroque Era of Western Classical Music. Species Counterpoint continued to be a practical way of composing through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance Era, but things started to change in the 17th century. At this time, while polyphonic counterpoint was still very important, CHORDS and HARMONY began to receive more consideration and a new style of composition, music analysis, and music theory evolved known as FIGURED BASS. Before we learn about Figured Bass and the way to compose in this style (called voice leading), let’s listen to some music that is composed in this style:

As you watch the music go by, notice a few things between what you hear and what you see:

The top line is in treble clef, labeled Flauto Traverso (Transverse Flute - aka “flute”), and we can hear it played on the flute.

The bottom line is in bass clef, labeled Continuo (short for Basso Continuo which translates to “Figured Bass”), and we can hear it played on the cello.

There is a harpsichord playing notes and chords (mostly triads) even though there are no chords written in the music that we can see.

There are a bunch of numbers and a few symbols written below the Continuo line that we don’t understand (this is the “figured” part of Figured Bass)

NO FIGURED BASS

FIGURED BASS

Just a Flute & Cello Duet

Added Figured Bass: 7 - 6 - # - 7 - 6 - 6 - 7 - 6 - 6/5

Without the Figured Bass symbols, the example above would just be a flute and cello duet (which still sounds really good!) but with the figured bass added, the duet provides enough information for a keyboard musician (such as a pianist, organist, harpsichordist - or even a harpist or guitarist) to play chords along with the music that will sound good accompanying the two composed lines. How a keyboardist does this is by IMPROVISING or AD LIBBING (performing in the moment rather than reading ahead of time) chords that will fit the continuo bass line and the symbols below each note. They do so with voice leading guidelines that are almost identical to the guidelines we learned for Species Counterpoint. Here is how it works …

FIGURED BASS

FIGURED BASS is a music notation style that provides symbolic information below a bass note to inform harmony, including: chord root, chord type, and chord quality. Figured bass is also referred to as BASSO CONTINUO or THOROUGH BASS (they are all the same thing).

Given a key signature, a single note in the bass, and the presence (or lack) of symbols/figures below the note, we can build a 4-note chord that is playable by a single person on a keyboard or singable by a four-part choir with voices in the Bass, Tenor, Alto, and Soprano ranges (like your voice ranges for sight singing). This style of writing is called SATB PART WRITING (for Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass) and you will notice that each voice stay in the same area of a clef and the stems point in the same direction. SOPRANO and ALTO stay in the treble clef and TENOR and BASS stay in the bass clef. The Soprano and Tenor “voices” (melodies) always use stems up and the Alto and Bass voices always use stems down.

BUT TRIADS DON’T HAVE FOUR NOTES …

You are correct! Triads only have three notes, but we have four “voices” (SATB) to assign a note from the three-note triad. So what do we do?

We will DOUBLE a chord tone, meaning that it will appear in two voices. Most of the time, you should double the bass note somewhere above in the Tenor, Alto, or Soprano voice. In the figure above, the SATB voicing of the chord is: C - G - E - C (reading from the bottom up). When we put these notes in order to make a triad, they spell Cx2 - E - G which is a C Major triad with the Root doubled in the Bass and Soprano. There is one exception to the “double the Bass note” rule below.

In Music Theory II, we will introduce a four-note chord (called a seventh chord because it uses the scale degrees 1 - 3 - 5 - 7) that will then fill up all four voices of the SATB part writing.

HOW DO I KNOW WHAT NOTE TO PUT WHERE?

There are no strict rules here, but there are best practices and these guidelines tend to be identical to Species Counterpoint guidelines. You have a lot of freedom of where you can place the notes of your first chord - after your first chord, you will base each next chord on the previous chord. When deciding where to place each note, follow these three guidelines:

Put the notes in the range a singer/vocalist could sing for that voice part.

Keep your Soprano, Alto, and Tenor voices within an octave of each other (S - A ≤ P8; A - T ≤ P8). The Bass can be over an octave lower than the Tenor but try to keep it ≤ P12

Spread your chord tones out so that there is room for chord tones between the Soprano, Alto, and Tenor - this is called OPEN VOICING (when your chord tones in S, A, and T are so close that no chord tones can fit between them, that would be called CLOSED VOICING). Open voicing gives you more room to move around with each new chord than closed voicing does.

When moving to a new chord, keep COMMON TONES (notes that are in both chords) in the same voice when possible and move the rest of the voices to the closest chord tone possible.

Don’t allow any voices to leap over an octave and try to keep leaps under a M6 at all times.

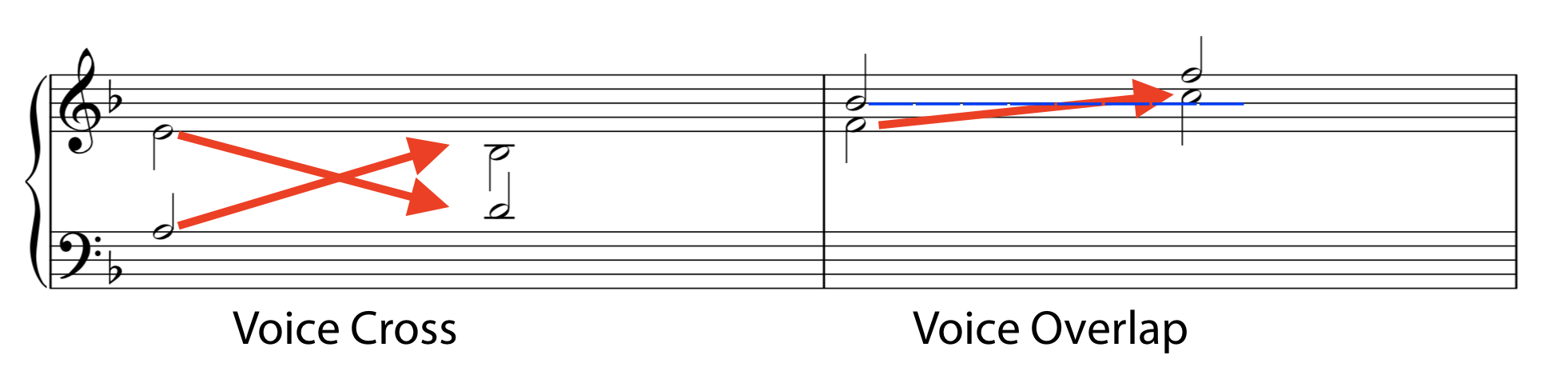

Do not VOICE CROSS (do not allow the S and A, A and T, or T and B to switch vertical positions) or VOICE OVERLAP (do not allow one voice to jump past the previous position of another adjacent voice on the next note).

An A Major Triad in 4-part voicing

Here are two examples of good open and closed voicing for the chord A Major (two A’s, a C#, and an E). Notice that the bass note doesn’t change for either; you can only control what’s in the Soprano, Alto, and Tenor, not what’s in the Bass. In addition, notice that the S, A, and T parts are all within an octave of each other, even in open voicing. The third example is incorrect for a variety of reasons.

INTERPRETING

FIGURED BASS NOTATION

Below are descriptions and examples of what to do depending on what kind of figured bass you encounter.

NO SYMBOl

When there is no symbol below a bass note, you know to use the diatonic triad from the key signature with the Bass note as the Root of the triad - this is called a triad in ROOT POSITION. A DIATONIC CHORD is a chord that is created by only using scale degrees from a scale, not notes outside the scale. Take the notes in the key of C Major: C - D - E - F - G - A - B - C. If we built a triad off of each scale degree, using only the notes available in the scale, here is what the triads and chord qualities would be:

1 - 3 - 5 (C - E - G) = C Major Triad (a major triad starting on the first scale degree)

2 - 4 - 6 (D - F - A) = D Minor Triad (a minor triad starting on the second scale degree)

3 - 5 - 7 (E - G - B) = E Minor Triad (a minor triad starting on the third scale degree)

4 - 6 - 1 (F - A - C) = F Major Triad (a major triad starting on the fourth scale degree)

5 - 7 - 2 (G - B - D) = G Major Triad (a major triad starting on the fifth scale degree)

6 - 1 - 3 (A - C - E) = A Minor Triad (a minor triad starting on the sixth scale degree)

7 - 2 - 4 (B - D - F) = B Diminished Triad (a diminished triad starting on the seventh scale degree).

Notice that we don’t use any sharps or flats so we are only left with the chord qualities generated by using the notes that naturally occur in the scale. This is what makes these chords DIATONIC (when we alter chord tones by using sharps, flats, or naturals to raise or lower them, these would be called chromatic chords). The pattern of triads above: [major - minor - minor - major - major - minor - diminished] is a constant no matter what major scale you are using. There is also a pattern of triads for minor scales that will be discussed later.

So, if I’m in C Major and I see the note “C” in the bass with no symbol below, I know I need to compose a C Major triad. If I see a G with no symbols, it’s a G Major triad, an A with no symbols, it’s an A Minor triad, and so on.

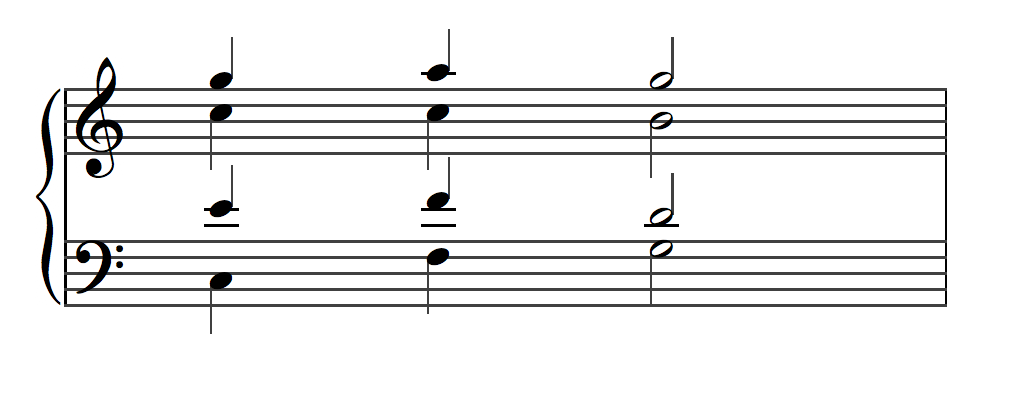

Let’s look at this example and two solutions:

The first thing we do is look at the key signature - in this example, there is none - to determine the key and scale we’re using. No sharps and no flats means we’re in C Major (or possibly A Minor but we’ll learn how to decide that later). Because there are no symbols below the bass notes, we know we can build the diatonic triad off of each note, and prepare to double the Root.

While keeping the same exact notes in the bass, we can decide where we want the other three chord tones to go in the Tenor, Alto, and Soprano voices. In Solution 1, the C chord’s Root is doubled above the Bass at the Tenor in an octave while the G is a P5 above the Tenor in the Alto and the E is a M6 above the Alto in the Soprano. It is in open voicing (since there is room between the chord tones for other chord tones) and the voices all move stepwise to the next chord’s chord tone or keep common chord tones (like the Tenor on C - C). From the F to G chord, however, the Tenor voice leaps from F down to D in order to avoid parallel octaves (where the Bass and Soprano would both move from F - G) and to keep the right number of chord tones (GG B D). In Solution 2, the open voicing is even more open with the Tenor over an octave above the Bass on an E, the Alto a m6 above on C, and the Soprano a P5 above on G. The horizontal movement is all identical to Solution 1, but our starting chord is a different voicing, so all the chords are voiced differently. Since Solution 2 has a wider range between bass and soprano, it would be considered a slightly more dramatic voicing.

SOLUTION 1

SOLUTION 2

NUMERICAL SYMBOLS

Numerical symbols change either the TYPE of chord (i.e. a seventh chord) or the INVERSION of the chord (the order of the chord tones). For Music Theory I, you will not be given an seventh chord examples, but the number you would see for these would be 7. You will, however, be given a few inversions to deal with and here is how they work:

When you see a 6 below a bass note, you will write the chord in FIRST INVERSION. You will still use two Rs, the 3rd, and 5th (1 - 1 - 3 - 5) but the Root will not be in the bass. The number 6 means that the bass note is the 3rd of the chord and the Root is a sixth above the third in the bass. This is because if you remove the Root from the bottom of the chord and place it up an octave, it will be a sixth above the 3rd in the bass.

The first inversion triad is the only version where you don’t double the Bass. Instead, you double the Root twice above the Bass.

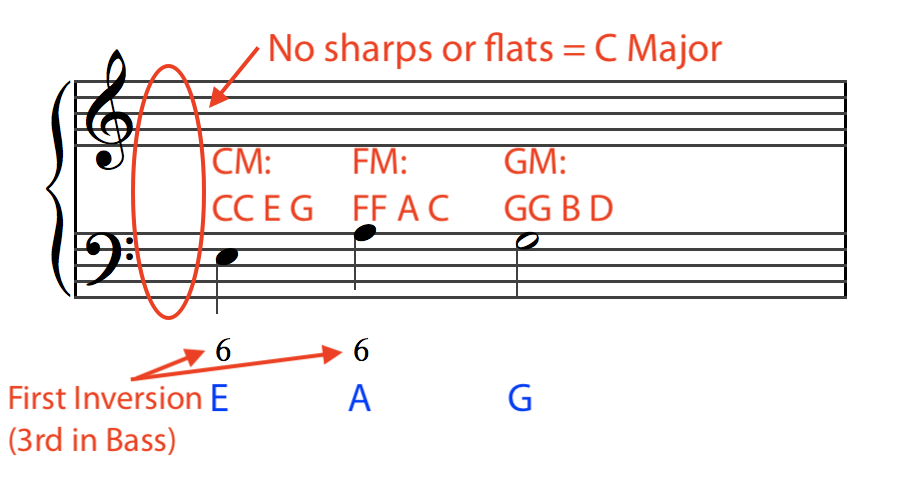

Here is an identical progression of chords as the example of Figured Bass above - except now we have two chords in first inversion:

As above, we will choose what chord tones to place in the upper voices (Soprano, Alto, and Tenor) based on what is already in the Bass and then following voice leading guidelines. We know each of our three triads (CM, FM, and GM) need two Roots, and 3rd and a 5th. The 3rd is already taken care of in the first two chords (CM and FM) because they’re in first inversion. This means that our options for notes above the Bass are two Roots and the 5th. In the final chord (GM), because it is in Root position, we need to add a Root, 3rd, and 5th above the Bass. Here are two solutions. Both are considered open voicing (you can fit chord tones between the voices) but Solution 2 is slightly more open since the voices are more spread out. They both have correct doublings of the Root of each chord, consonant melodic movement, a variety of relative motion, and the voice parts stay within an octave of each other. Since they are both correct, you could choose to compose one versus the other based on which melody (Soprano line) you like better or how open you want the voices to be.

SOLUTION 1

SOLUTION 2

When working with a bass note with the number 6 below it, treat the Bass as the 3rd of a diatonic chord and find the Root below and the 5th above - then fill in two Roots and a 5th in the Tenor, Alto, and Soprano voice above the Bass.

When you see a 6/4 (6 over 4) below a bass note, you will write the chord in SECOND INVERSION. For this chord, you will double the bass (the 5th) so the notes you will use are (1 - 3 - 5 - 5). The numbers 6/4 mean that the bass note is the 5th of the chord, the Root is a fourth above the 5th in the Bass and the 3rd is a sixth above the 5th in the Bass.

The second inversion triad is the only version where you don’t double the Root. Instead, you double the Bass twice, which results in two 5ths.

Here is another identical progression of chords as the examples of Figured Bass above - except now we have a chords in second inversion:

To complete this figured bass, we will choose what chord tones to place in the upper voices (Soprano, Alto, and Tenor) based on what is already in the Bass and then following voice leading guidelines. Each of the triads are in a different inversion. The Root Position and First Inversion triad will each need two Roots, a 3rd, and a 5th. The Second Inversion triad will need a Root, a 3rd, and two 5ths. Here are two solutions and a third problematic one. All three start with the same exact voicing on beat 1 and have correct doublings, voice ranges, open spacing, and use common tones, steps, or small melodic leaps. Solution 1 and 2 differ because Solution 2 opens up more than Solution 1 with wider spacing at the end. Solution 1 has the Tenor and Bass voice coming together to double a unison Root in the last chord - which is perfectly acceptable to do (just have both stems coming off the note). The third solution looks fine until you notice the illegal parallel fifth between the Soprano and Alto voice.

SOLUTION 1

SOLUTION 2

SOLUTION WITH ERROR

When working with a bass note with the numbers 6/4 below it, treat the Bass as the 5th of a diatonic chord and find the root and 3rd below - then fill in a Root, a 3rd, and another 5th in the Tenor, Alto, and Soprano voice above the Bass.

NON-NUMERICAL SYMBOLS

Most non-numerical symbols refer to accidentals - letting you know to raise or lower different chord tones above the bass. This happens more often in minor keys but will also happen in major keys on occasion. There are five symbols in addition to numbers that you may encounter: ♯ (sharp), ♭ (flat), ♮(natural), + (plus), or a number with a slash through it. When you encounter these symbols, do the following:

In this example, the “slashed 6” means to sharp the note 6 above the Bass - which means to include an A♯ in this chord.

♯ SHARP: Raise the note by one half step from its position in the key signature (B♭→ B♮)

+ PLUS: Treat the same as a sharp

SLASHED NUMBER: Treat the same as a sharp

♭ FLAT: Lower the note by one half step from its position in the key signature (F♯→ F♮)

♮NATURAL: Use the natural version of this note, regardless of its position in the key signature (B♭→ B♮ and F♯→ F♮)

If you see the symbol by itself, it is referring to the 3rd of the chord. If you see the symbol referring to any other number (i.e. ♭6), then alter the note that distance above the bass, which could be a chord tone in inversion.

I didn’t make the rules, sorry :( - Dr. Bove

ILLEGAL MOTION

Because Music Theory has absolutely no chill, there are certain things you never want to do because they are considered illegal. Not illegal in the sense that you would get thrown in jail over them, but more that there are rules that never have exceptions (in strict music theory contexts - in “the real world,” composers do break these rules all the time). The following are things you should never do without exception:

DISSONANT MELODIC MOVEMENT: Never move a voice to a dissonant interval away such as a tritone or major or minor seventh.

PARALLEL FIFTHS, UNISONS AND OCTAVES: Never write a P5, P8, or P12 (P8 + P5) in two voices and then keep that exact interval in the same two voices for the next chord.

DOUBLE ACCIDENTALS: If your chord calls for an accidental outside the key, only use it in one voice, not two.

DOUBLE LEADING TONE: Never double the 7th scale degree of the key you are in.

UNRESOLVED ACCIDENTALS: If a note is raised (“sharped”), it should move up on the next note; if a note is lowered (“flat”), it should move down on the next note.

VOICE CROSSING AND VOICE OVERLAPPING: Never allow your voices to cross range (check especially between Alto and Tenor) or overlap.

While overlapping is illegal, you can allow a voice to inhabit the same spot an adjacent voice previously held

… RULES WERE MADE TO BE BROKEN

As alluded to in the Species Counterpoint unit, we learn the rules so we can intentionally break them to create surprise and drama. In general, there are several rules that are often broken, and here is how:

ALWAYS RESOLVE 7 UP TO 1 … except sometimes you can resolve it down to 5. Just please don’t do this on the very last chord of the piece.

NEVER COMPOSE PARALLEL 5ths … unless it is a P5 moving to a d5 or a d5 moving to a P5 … diminished fifths don’t count - but try to avoid using d5s in general. P5 - d5 or d5 - P5 are technically not parallel movements since the interval changes by a half step.

KEEP COMMON CHORD TONES … unless your line is getting melodically boring. Sometimes you can keep the same note in the Alto voice for almost the entire

USE ALL THREE CHORD TONES … unless that creates some worse, illegal problem, then omit the 5th and double the Root and the 3rd

DOUBLE THE BASS NOTE … unless you are in first inversion (then double the Root), or doubling the Bass note will cause illegal problems

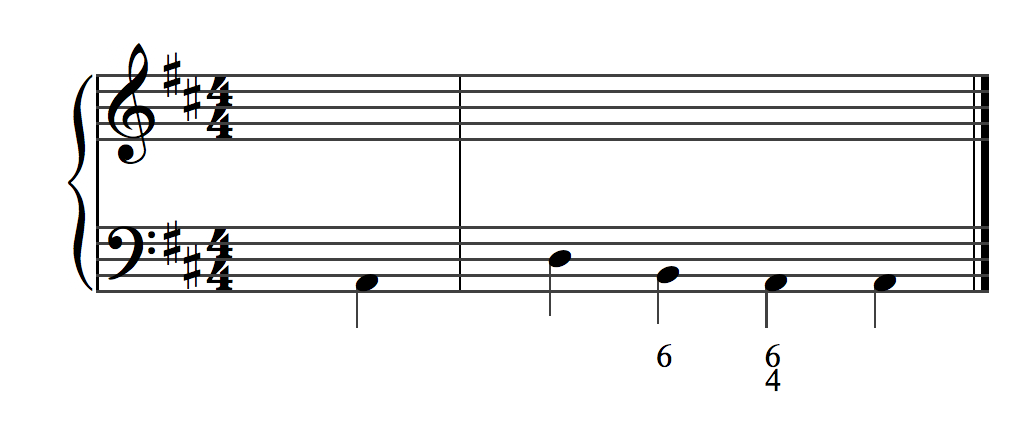

REALIZING FIGURED BASS IN ACTION

Here is a 4-chord exercise to try on your own. It is in the key of D Major. Follow the steps below to compose your own Figured Bass, then check how you did by watching the tutorial video. You may come up with a correct realization that is different from the one I do - that’s okay! As long as you are avoiding illegal motions and following the voice leading/species counterpoint guidelines we have been working on for weeks, your realization will be correct!

I recommend composing your Figured Bass exercises in music notation software (like MuseScore, Finale Notepad, or Sibelius|First) because of the “playback” feature that allows you to play and listen to your composition while you’re working on it and after it’s complete.

***I forgot to mention in the video!

This 5-chord example is in 4/4 time but there is a single quarter note by itself in a very short “measure zero” before the first full measure with four beats. This is called a “pick-up” (in layman’s terms) and an ANACRUSIS in music terminology. It is a weak start to a song or piece of music before the first main beat arrives. Think of the song “Happy Birthday”: “Hap-py BIRTH-day to YOU, hap-py BIRTH-day to YOU, hap-py BIRTH-day dear SO-n-so, hap-py BIRTH-day to YOU!”. This song is in 3/4 with a pick-up on the word “happy” before the real beat 1 of each measure. You can feel the strength of the beat (on beat 1) if you sing “Happy Birthday” and nod your head to emphasize each of the bolded lyrics above.